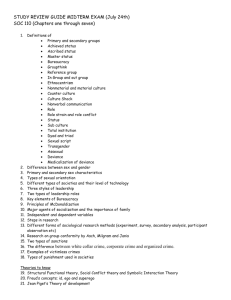

Crime and cohesive communities

advertisement

Crime and cohesive communities Dr Elaine Wedlock Home Office Online Report 19/06 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors, not necessarily those of the Home Office (nor do they reflect Government policy). Crime and cohesive communities Dr Elaine Wedlock Research, Development and Statistics – Communities Group Home Office Online Report 19/06 Key findings • Cohesive communities have five key attributes: o Sense of community; o Similar life opportunities; o Respect for diversity; o Political trust; and o Sense of belonging • Local areas with a high sense of community, political trust and sense of belonging show significantly lower levels of ‘all’ reported crime. • Rates for different types of crime are predicted to reduce as sense of community goes up. Type of reported crime Decrease in crime as sense of community increases by one unit All crime Burglary from dwelling Theft of motor vehicle Theft from motor vehicle Violent crime 3% 3% 4% 2% 3% 2 Introduction This paper uses data from the Local Areas Boost to the 2003 Home Office Citizenship Survey in order to investigate the relationship between community cohesion and reported levels of crime. The 2003 Local Areas Boost took an in-depth case study approach to the measurement of community cohesion in 20 local areas. It provided evidence of progress towards Home Office PSA Target 9 which aimed to ‘bring about measurable improvements … in community cohesion across a range of performance indicators as part of the government’s objectives on equality and social inclusion’. Each local area was made up of two contiguous wards with a random sample of approximately 500 respondents: 10,138 respondents in total. A thematic analysis of this survey data identified the following five key factors of community cohesion: sense of community; similar life opportunities; respect for diversity; political trust and sense of belonging. Data on these factors was linked with reported crime data collected directly by police forces in ten of the local areas. Previous academic research has shown a link between social control as an aspect of community cohesion and decreases in violent crime. This paper seeks to build on the evidence by investigating the links between other key aspects of cohesive communities and levels of reported crime. It investigates whether these factors are related to violent crime as well as identifying links with other types of neighbourhood level reported crime. Local area case studies of community cohesion The 2001 disturbances in Bradford, Oldham and Burnley drew attention to the role of community cohesion in developing strong, healthy communities. Reports into the disorder identified a common theme of a lack of interaction between individuals of different cultural, religious and racial backgrounds in local areas. Commentators drew attention to community cohesion as instrumental in promoting greater knowledge, respect and contact between various ethnic groups, and in establishing a greater sense of citizenship. In December 2002, the Local Government Association, Home Office, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Commission for Racial Equality and the Inter-Faith Network developed guidance for local authorities on community cohesion. It defined a cohesive community as one where: • there is a common vision and a sense of belonging for all communities • the diversity of people’s different backgrounds and circumstances is appreciated and positively valued • those from different backgrounds have similar life opportunities • strong and positive relationships are being developed between people from different backgrounds in the workplace, in schools and within neighbourhoods. Based on this description, researchers developed a set of questions to measure attitudes towards the local neighbourhood; perceptions of others in the neighbourhood; sense of belonging; valuing diversity; similar life opportunities; race discrimination; interaction with others; positive relationships; influencing political decisions and trust in organisations. In 2003, the Local Areas Boost used these questions along with the following single item indicator to gain a baseline measure of community cohesion in 20 local areas: ‘the proportion of people who feel that their local area is a place where people from different backgrounds get on well together’. This provided the evidence of progress towards Home Office PSA Target 9 which aimed to ‘bring about measurable improvements … in community cohesion across a range of performance indicators as part of the government’s objectives on equality and social inclusion’. The 2003 survey consisted of around 500 interviews conducted in each of the 20 areas. A total of 10,138 interviews were conducted. Interviews lasted 30 minutes, they were conducted face-to-face, 3 in-home using Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI). The interview schedule contained 32 questions developed to measure community cohesion. The relationship between crime and community cohesion As far back as 1974 Kasarda and Janowitz developed a model of community attachment. The model predicts that high levels of local integration lead to members of the community sharing the same values and goals. The strongest of these goals is to keep the neighbourhood safe and free from crime. Implicit in this theory is a form of social control which sets norms of behaviour that people must abide by if they want to remain within that community. Sampson and Groves (1989) used the 1982 and 1984 waves of the British Crime Survey to investigate the links between this form of community cohesion and victimisation. They found that community cohesion was directly linked to a reduction in mugging, street crime and stranger violence. Sampson and Raudenbush (1999) found that social control takes the form of people in cohesive neighbourhoods being prepared to pull together and intervene in deviant or criminal activities for the public good. They defined this type of collective efficacy as ‘cohesion amongst residents combined with shared expectations for the social control of public space’. They found that collective efficacy is associated with lower rates of crime and social disorder even after controlling for structural characteristics of the neighbourhood. Hirschfield and Bowers (1997) also investigated the links between crime and social cohesion (defined as levels of social control and ethnic heterogeneity). Their results suggest that levels of crime are significantly lower than expected in areas that are disadvantaged but have high levels of social cohesion. Again this shows that the levels of community cohesion can transcend factors of public disorganisation such as deprivation that have traditionally been seen to be the strongest predictors of becoming a victim of crime. The links between cohesive communities and reduced crime are not only a British and American phenomenon. Lee (2000) used data from 15 countries in the 1992 wave of the International Victimization Survey in order to provide an international comparison of the role that community cohesion plays in reducing the risk of individual violent victimization. He found that the higher levels of social control or guardianship apparent in a cohesive community reduce the likelihood of becoming a victim of violent crime such as robbery and assault, regardless of socioeconomic status, lifestyle and neighbourhood characteristics. Studies such as these have largely found links between social control as a form of community cohesion and becoming a victim of different forms of violent crime. Other studies such as Massey, Krohn and Bonati (1989) attempted to discover whether there are links between having social ties within a neighbourhood and property victimisation. This study was unable (largely due to methodological reasons) to provide robust evidence of the links between strong, joined up communities and becoming a victim of property crime. Along with violent crime, which has been investigated in these other studies, this paper also investigates the links between community cohesion and other types of recorded crime that take place at a neighbourhood level such as burglary from dwelling and non-dwelling, theft of and from motor vehicles and an overarching ‘all’ reported crime measure. Previous studies on the links between community cohesion and crime have also largely concentrated on social control or guardianship facets of community cohesion. This paper uses empirical data in order to identify five key factors of community cohesion. It then goes on to investigate the impact of these key factors on the five types of reported crime. 4 Key factors of community cohesion Factor analysis is a statistical tool used to organise and reduce large sets of questions that explore a single theme. It uses patterns of responses to identify how questions cluster together around subthemes or factors. A factor analysis of the 32 questionnaire items around community cohesion from the Local Areas Boost data set was used to identify the key underlying themes associated with community cohesion. Consistent with standard practice, factors that explained very little variance in community cohesion were discarded1, leaving a total of five key factors of community cohesion. 2 In total, the five factors explained 38.5% of the variance in community cohesion and each of the five factors is significantly correlated with the single item measure of community cohesion. 3 The questions clustered around the following five themes or factors: • Sense of community: for example whether people enjoy living in their neighbourhood and are proud of it, whether people look out for each other and pull together. • Similar life opportunities: the extent to which people feel they are treated equally by a range of public services. • Respecting diversity: whether people feel that ethnic differences are respected within their neighbourhood. • Political trust: do people feel they can trust local politicians and councillors and do they feel that their views are represented? • Sense of belonging: whether people identify with their local neighbourhood and know people in the local area. These combinations of questions produce five measures which explain more of the variance in community cohesion than the questions would individually. Each of the factors has a high level of internal consistency. This means that every question within the factor measures a slightly different aspect of the same theme. 4 The questions were then combined into five composite variables to be used in further analysis.5 It is interesting to note that although the sense of community factor contains some aspect of social control, there are other elements that add to this measure and make it a stronger factor and able to explain more variance in community cohesion than social control variables alone. The questions around whether people feel safe walking after dark, whether neighbours look out for each other, trust each other and pull together to improve the community are all measures of social control. However, the other measures within the sense of community are more about a type of camaraderie; whether people are proud of their neighbourhood and enjoy living there. The sense of belonging factor also has elements of social control or guardianship, for example whether respondents know many people in the area and feel that they belong to the neighbourhood, implying an element of socialization or being embedded in the neighbourhood. The factor analysis has, however, separated out the sense of belonging which is a form of being embedded in the neighbourhood, from the ability to feel a sense of community and camaraderie in the local area which loads into a separate factor. It is possible then to perceive a sense of community without having lived in the area for a long time. Data for these five factors was linked with reported crime data collected directly by police forces in ten of the local areas. This ward level dataset was used to investigate the correlation between factors of community cohesion and reported crime. It was then used to investigate which of the five factors 1 Factors with an eigenvalue less than 1. See Appendix 2 for factor loadings. 3 See Appendix 3 for correlation matrix. 4 See Appendix 4 for note on the Cronbach’s Alpha test for internal validity. 5 Any missing values refer to respondents who did not answer any of the questions within each factor. If the respondent has not answered any of the questions then it is coded as missing. All factors were coded so that response code 1 is the most positive answer and response code 5 is the most negative answer. In the case of the similar life opportunities factor, the ‘I would be treated worse’ and ‘I would be treated better’ response codes were treated as the most negative reponse and ‘I would be treated the same’ is coded as the most positive response. 2 5 could significantly predict the following reported crime measures: all crime, burglary from dwelling, burglary from non-dwelling, theft of motor vehicle, theft from motor vehicle and violent crime. Relationship between community cohesion factors and the all crime measure Correlation analysis of the community cohesion factors and the ‘all crime’ measure indicates that sense of community, political trust and sense of belonging are all significantly related to decreases in the ‘all crime’ measure.6 The sense of community factor explains the largest proportion of variance in the ‘all crime’ measure. Table 1: Correlation of community cohesion factors and ‘all crime’ Log of all crime Sense of community Log of all crime - Sense of community Similar life opportunities Respecting diversity Political trust -.76** - Similar life opportunities -.43 .60** - Respecting diversity -.32 0.39 .50* - -.64** 0.82** 0.73** 0.60** - -.55** .81** 0.74** 0.28 0.60** Political trust Sense of belonging Sense of belonging - ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2 tailed) * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2 tailed) Factors of community cohesion as key drivers of reported crime All five factors of community cohesion were entered as variables into a forward stepwise regression model7 as potential predictors of the various types of reported crime. The level of multiple deprivation for each ward was also added into the models in order to test whether the deprivation level experienced within the area is more important than the factors of cohesion in predicting crime. In the ten case study areas the sense of community factor is the strongest predictor of ‘all crime’, burglary from dwellings, theft of motor vehicles and theft from motor vehicles, regardless of the level of deprivation. The model for violent crime shows that the level of deprivation and the sense of community are both key predictors of recorded levels of violent crime. Table 2 shows the degree to which each of these measures of recorded crime is predicted to decrease when the sense of community within an area goes up by one unit. This is graphically represented in Figures 1 and 2 below: 6 See Appendix 4 for note on methods of analysis. A forward stepwise regression programme selects one independent variable at a time to enter into the model. Each time it enters an independent (predictor) variable into the model it tests how much of the variance is explained in the dependent variable. The variable that explains the most variance is then kept in the model. The model is built up in this step by step manner by keeping independent variables that explain a significant amount of the variance in the dependent variable. The models tested which combination of the five factors of cohesion and level of deprivation (the independent variables) can be most effectively used to predict the different types of recorded crime (the dependent variable). 7 6 Table 2: The predicted percentage decrease in crime measures as sense of community increases by one unit. All crime Burglary from dwelling Burglary from non-dwelling Theft of motor vehicle Theft from motor vehicle Decrease in crime as sense of community increases by one unit 3% 3% No significant relationship 4% 2% Table 3 shows that as the Index of Multiple Deprivation score increases by one unit, violent crime is predicted to increase by 3 per cent, and as the sense of community increases by one unit, violent crime is predicted to decrease by 3 per cent. In effect an increased sense of community negates the impact of high deprivation upon violent crime. Table 3: The predicted percentage change in violent crime as sense of community and index of multiple deprivation score increase by one unit. Predictor variable Sense of community IMD % change in violent crime with a one unit increase in the predictor variable -2.7% 2.6% 7 Figure1: The relationship between sense of community and ‘all crime’ Crime rate (all crimes) per '000 population 250 200 150 100 50 0 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Sense of community 8 Figure 2: Relationship between sense of community and other reported crime measures 35 30 Crime rate per '000 population 25 20 Burglary from dwelling Theft of motor vehicle Theft from motor vehicle All violent crime 15 10 5 0 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Sense of community 8 For the purposes of this graph, the index of multiple deprivation score has been set to 24.3078 which is the average IMD across the wards in this analysis. 8 Conclusions Although previous studies such as Lee (2000) have linked community cohesion with decreases in crime, they have tended to focus on the social control aspect of community cohesion. A thematic analysis of data from 10,138 respondents on questions around community cohesion has identified five key aspects of community cohesion. The sense of community factor was found to be the strongest predictor of various types of recorded crime. This sense of community factor is made up of some questions that include elements of social control such as whether people pull together to improve the area, whether they feel safe walking at night, whether neighbours look out for each other and whether they trust people in their neighbourhood. It also includes a more general sense of camaraderie such as whether people enjoy living in the area and are proud of the neighbourhood. The sense of belonging factor also contains aspects of social control. This measures whether respondents know many people in their neighbourhood and whether they feel a sense of belonging to the local area and neighbourhood. This factor is not a strong predictor of lower levels of crime. This means that you don’t need to feel a strong sense of attachment to an area in order to benefit from the sense of community that is linked with lower levels of crime, which somewhat negates Kasarda and Janowitz’s theory that high levels of attachment lead to local integration and the shared goal of keeping the neighbourhood safe. A sense of community rather than a sense of attachment is the most important predictor of lower levels of crime. This is good news for areas with high population turnover, particularly because this sense of community is not only linked with lower levels of violent crime (the type of crime most often linked with social control), but also with other types of neighbourhood level crime such as burglary from dwelling, theft of and from motor vehicles and the overarching ‘all reported crime’ measure. 9 References Hirschfield, A. and Bowers, K. J. (1997) The Effect of Social Cohesion on Levels of Recorded Crime in Disadvantaged Areas. Urban Studies. 34: 1275 – 1295. Kaiser, H. F. (1960) The application of electronic computers to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141 – 151. Kasarda, J. and Janowitz, M. (1974). Community Attachment in Mass Society. American Sociological Review 39: 328 – 39. Lee, M. R. (2000) Community Cohesion and Violent Predatory Victimization: A Theoretical Extension and Cross-national Test of Opportunity Theory. Social Forces. 79 (2): 683 – 688. Massey, J. L., Krohn, M.D. and Bonati, L. M. (1989) Property Crime and the Routine Activities of Individuals. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 26: 378 – 400. Sampson, R. J. and Groves. W. B. (1989) Community Structure and Crime: Testing SocialDisorganization Theory. American Journal of Sociology 94: 774 – 802. Sampson, R. J. and Raudenbush, S. (1999) Systematic Social Observation of Public Spaces: A New Look at Disorder in Urban Neighbourhoods. American Journal of Sociology 105: 603 – 651. 10 Appendix 1. Questions that make up the five factors of community cohesion Factors of community cohesion Factor 1: Sense of community (1) Taking everything into account, how would you describe your overall attitude towards the local neighbourhood. Would you say you feel……. (1) very proud of the local neighbourhood (2) fairly proud of the local neighbourhood (3) not very proud of the local neighbourhood (4) or not at all proud of the local neighbourhood? (5) DON’T KNOW (2) Would you say that this is a neighbourhood that you enjoy living in? (1) Yes, definitely (2) Yes, to some extent (3) No (3) Would you say that…. (1) Many of the people in your neighbourhood can be trusted (2) Some can be trusted (3) A few can be trusted (4) Or that none of the people in your neighbourhood can be trusted? (5) JUST MOVED HERE (6) DON’T KNOW (4) Would you say this neighbourhood is a place where neighbours look out for each other? (1) Yes, definitely (2) Yes, to some extent (3) No? (4) JUST MOVED HERE (5) DON’T KNOW (5) And how safe would you feel walking alone in this neighbourhood after dark? (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) Very safe Fairly safe A bit unsafe Very unsafe NEVER WALKS ALONE AFTER DARK DON’T KNOW (6) To what extent do you agree or disagree that people in this local area pull together to improve the area? (1) Definitely agree (2) Tend to agree (3) Tend to disagree (4) Definitely disagree (5) DON’T KNOW (6) NOTHING NEEDS IMPROVING 11 Factor 2: Similar life opportunities In a moment I am going to read out a list of services. For each one, I’d like you to imagine you are a member of the public using each service, and for you to tell me, using this card, if you would expect that they might treat you better than people of other races, worse than people of other races, or about the same. It doesn't matter if you haven’t had any direct contact with the organisations, it's just your opinions I’m after. (1) Firstly, how do you think a local doctor’s surgery would treat you: worse than people of other races, better than people of other races, or the same as people of other races? (1) (2) (3) (4) I would be treated worse than other races I would be treated better than other races I would be treated the same as other races DON’T KNOW/ NO OPINION then as above for the following organisations (2) local school (3) local council housing dept. or housing association (4) local council (5) local Job Centre (6) local courts – magistrate or crown court (7) local police Factor 3: Respect for diversity Now I would like to ask you some questions about your local area. I mean the area within 15-20 minutes walking distance from here. I am now going to read out a number of statements and I would like you tell me to what extent you agree or disagree with each. (1) Residents in this local area are generally unhappy when people from different ethnic groups move here. (1) Definitely agree (2) Tend to agree (3) Tend to disagree (4) Definitely disagree (5) DON’T KNOW (2) This local area is a place where residents respect ethnic differences between people. (1) Definitely agree (2) Tend to agree (3) Tend to disagree (4) Definitely disagree (5) DON’T KNOW (3) How much tension between people from different ethnic groups would you say there is in this local area? (1) A great deal (2) A fair amount (3) A little (4) None at all (5) DON’T KNOW (4) Having a mix of different people in this local area makes it a more enjoyable place to live. (1) Definitely agree (2) Tend to agree (3) Tend to disagree (4) Definitely disagree (5) DON’T KNOW 12 Factor 4: Political trust (1) To what extent do you agree or disagree that local MPs (Members of Parliament) represent your views? (1) Definitely agree (2) Tend to agree (3) Tend to disagree (4) Definitely disagree (5) DON’T KNOW (2) To what extent do you agree or disagree that local councillors represent your views? (1) Definitely agree (2) Tend to agree (3) Tend to disagree (4) Definitely disagree (5) DON’T KNOW Now I would like to ask a few questions about trust. Firstly, how much do you trust…. (3) Local politicians (1) A lot (2) A fair amount (3) Not very much (4) Not at all (4) And your local council (1) (2) (3) (4) A lot A fair amount Not very much Not at all Factor 5: Sense of belonging I am going to read out a number of different areas. I would like you to tell me how strongly you feel you belong to each of the following? (1) Your immediate neighbourhood (1) Very strongly (2) Fairly strongly (3) Not very strongly (4) Not at all strongly (5) DON’T KNOW (2) This local area. I mean the area within 15-20 minutes walking distance from here (1) Very strongly (2) Fairly strongly (3) Not very strongly (4) Not at all strongly (5) DON’T KNOW (3) Would you say that you know… (1) Many of the people in your neighbourhood (2) Some of the people in your neighbourhood (3) A few of the people in your neighbourhood (4) Or that you do not know people in your neighbourhood? (5) JUST MOVED HERE (6) DON’T KNOW 13 Appendix 2: Orthogonal rotation component analysis of variables measuring community cohesion Question number and item (1) Proud of living in the local neighbourhood (2) Enjoy living in neighbourhood (3) Trust in people in neighbourhood (4) Neighbours look out for each other (5) Safety (6) People in the local area pull together (1) Local council non-discriminatory (2) Local courts non-discriminatory (3) Local Job Centre non-discriminatory (4) Local council housing non-discriminatory (5) Local police non-discriminatory (6) Local school non-discriminatory (7) Local doctor's surgery non-discriminatory (1)Unhappy when ethnic groups move here (2) Respect ethnic differences (3) Tension between different ethnic groups (4) Having a mix of different people (1) Local MPs represent your views (2) Councillors represent your views (3) Trust local politicians (4) Trust your local council (1) Belonging to neighbourhood (2) Belonging to local area (3) Know people in neighbourhood Factor loadings Sense of Similar life Respecting Political community opportunities diversity trust 1 0.73 0.72 0.68 0.57 0.55 0.53 0.68 0.67 0.66 0.66 0.65 0.53 0.46 -0.76 0.72 -0.66 0.61 0.84 0.83 0.53 0.50 Sense of belonging 0.34 0.82 0.81 0.58 Questions that did not load into the factors (1) Trust in local courts (2) Trust in local police (3) Trust local newspapers (4) Trust your employer (5) Influence decisions affecting local area (6) Influence decisions affecting local authority (7) Teach children about different cultures (8) Other people get unfair priority % variance explained 9.5 9.0 6.9 6.6 6.5 [Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. Rotation converged in seven iterations.] 14 Appendix 3: Correlation matrix of five factors of community cohesion and the single item measure of community cohesion Single item community cohesion measure Single item community cohesion measure Sense of community Sense of community Similar life opportunities Respecting diversity Political trust - 44** - .23** . .14** - Respecting diversity 59** .37** .29** - Political trust .26** .24** .24** .24** - Sense of belonging . 32** .56** .09** .20** .17** Similar life opportunities Sense of belonging ** Correlation is significant at the p<0.001 level (two tailed) 15 - Appendix 4: Note on methods of analysis Factor analysis The aim of the factor analysis was to reduce the complexity of the data set; to identify themes from the questions and to use these themes or factors as input to further statistical analysis. It uses patterns of responses to identify how questions tend to cluster together around the sub-themes. Exploratory factor analysis used the 32 questionnaire items around community cohesion from the Local Areas Boost data set. Factors that explained very little variance in community cohesion (factors with eigenvalues of less than one) were discarded, leaving a total of five. This is in line with Kaiser (1960) who suggested that an eigenvalue of one represents a substantial amount of variance. The first five factors also make intuitive sense and are in keeping with aspects of community cohesion that are discussed in the relevant literature. Composite variables and factor scores Within the composite variables any missing values refer to respondents who did not answer any of the questions within each factor. If the respondent has not answered any of the questions then it is coded as missing. All factors were coded so that response code 1 is the most positive answer and response code 5 is the most negative answer. In the case of the similar life opportunities factor, the ‘I would be treated worse’ and ‘I would be treated better’ response codes were treated as the most negative response and ‘I would be treated the same’ is coded as the most positive response. Questions were given equal weighting within the composite variable. In order to get a ward level score for each of the factors, the percentage of positive responses were taken. For example a 56% score on sense of belonging shows that 56% of respondents in the given ward responded positively to the set of questions around sense of belonging. Cronbach’s alpha Cronbach’s Alpha was used to check the reliability of each of these factors as a measurement scale; it shows the extent to which each of the items within the factor are related to each other based on the average inter-item correlation. Each of the factors were found to have acceptable internal consistency. The variables were then grouped together into composite variables using the weighted values from the factor analysis. Correlation analysis Correlation analysis is used to measure the relationship between two continuous variables, in this case the ‘all reported crime’ measure and the factors of community cohesion. Evidence of an association between variables does not imply a causal link. Log transformation of reported crime measures Regression analysis requires that the observed values of the dependent variable (in this case the ‘all crime’ measure) follow a normal distribution. The ‘all crime’ measure is a rate per 1000 of the population, it does not have much variance and so does not meet this requirement. It is standard in linear regression to perform a mathematical transformation of this type of dependent variable so that we can use linear regression techniques to describe curved or skewed relationship. The log transformation stabilises the variance as the rates have increasing variance with increasing size. This transformation is appropriate as without it the relationship would be multiplicative and not linear. In this case a log was taken of the ‘all crime’ measure in order to provide a normally distributed variable with variance for use in the regression modelling. 16 The scatterplot below shows the appropriateness of the log transformation for the ‘all crime’ measure. By creating a normally distributed ‘all crime’ measure we can see the linear relationship between all crime and sense of community. The scatterplot also shows that ward 19 is an outlier and has an extremely high measure of ‘all crime’. Ward 19 will be omitted from the analysis of the ‘all crime’ measure as it would skew the results; this is standard practice for outliers. Figure 3: Scatterplot of all crime by sense of community 19 Log of Crime Rate (all crimes) per '000 Population 6.50 6.00 5.50 5.00 4.50 4.00 R Sq Linear = 0.579 3.50 40.00 50.00 60.00 70.00 80.00 90.00 100.00 Sense of community In order to satisfy the assumptions of linear regression a log was also taken of each of the other reported crime rate measures in order to transform the variable into a normal distribution. Forward stepwise regression The forward stepwise regression process selects from a group of independent variables the one variable at each stage which makes the largest contribution to the R 2 (explains the most variance in the dependent variable). It stops admitting variables when they do not make a significant contribution 2. to the R The resultant model contains the significant independent variables that explain the most variance in the dependent variable. 17 All crime model residual analysis Normal P-P Plot of Regression Standardized Residual Scatterplot Dependent Variable: Log all crime Dependent Variable: Log all crime 1.0 Regression Standardized Residual 2 Expected Cum Prob 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 1 0 -1 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 -1.5 Observed Cum Prob -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 Regression Standardized Predicted Value Given the small number of cases, the normal probability plot does not suggest normality is unreasonable and the scatterplot supports the assumption of constant variance and the appropriateness of the linear model on the log-scale. 18 Produced by the Research Development and Statistics Directorate, Home Office This document is available only in Adobe Portable Document Format (PDF) through the RDS website http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds Email: public.enquiries@homeoffice.gsi.gov.uk ISBN 1 84473 925 2 Crown copyright 2006