Little Women

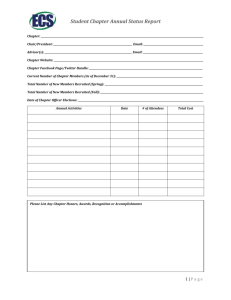

advertisement