1 Monster Culture (Seven Theses)

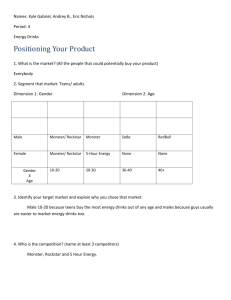

advertisement

•

1

Monster Culture (Seven Theses)

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen

ml'alling: post de M.m. po st Fouc;}ull. post II:lydell Whik, one must

bcar in mind that hi~tor y is j u~t another text in a proct'. jon of texlS, aJld

nor ~I gu,uantor of any, inglliar igniij at ion. A mowment a\\, ), from the

IOllgllt'd/l n: and toward mi rOl'co nomics (of capital or \If g\?nd~r is a~­

sociatl.'ti TlW,t often with Fouc,llilciian lriticism; yet rcxcnt criti(:. ha\'c

found that where Fout"ault Wl'nt wrong \\i~I~ mainly in his dl."r.lils, in

his minute specifi .. 'oJlerhele • his Illelhodolog ,- his. rchawlogy of

ideas. his histories of unthought-remains with ~o (ld Tl: ~l son (he chosen

route of inquiry for most cul·tural critit's today, whether they work in

postnlodcrn cyberculture or in the ~vliddle Abl's ,

And so J would like Lo make some grand gestures. \,Vl.' live in an age

that has right! .- given up on'nified Theory, an a~(; when we rcali7.~· thilt

history (like "individual it y." "s ubjectivity." "gender," and "culture" '

composed of a mu tit"

mological wholes, Some fragmcmts will be coUeered here Jnd bound

-tt1Ttfl~iH't!Y-*'l~oow.Q..j:ru:m....<Ll.o(;~lf-~teg ra ted net-or, bener, an

alher than argue a "theory of

3

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN, USA : University ofMinnesota Press, J996. P 3.

hllp:llsite.ebrary.comlliblbroolclynlDoc?id= JOJ 5 J042&ppg= 18

4

kttrcv lerom(' ( :ohcI1

<UiUUlII,¥.--J,.Ju.u~~J.l<.il~of

introduction to the es!>ays that follow a set

search of specific cultural moments. I offer

seven theses toward understanding cultures through the monsters they

bear.

Thesis I: The Monster's Body Is a Cultural Body

Vampires, burial, death: inter the (orpse where the road forks, so that

when it springs from the grave, it wiU not know which path to follow.

Drive a stake through its heart: it will be stuck to the ground at the fork,

it will haunt that place that leads to many other places, that point of indecision. Behead the corpse, so that, acephalic, it \V,ill not know itsdf as

subject, only as pure body.

The monster is born only at this metaphoric crossroads, as an embodiment of a certain c.ultural moment-of a time, a feding, and a place. t

The monster's bod quite literally incorporates fear, desire, anxiety, and

fanta~y (ataractic 0 incendiar -I, iving them life and an uncann)' independence The monstrous body is pure culture. construct and a

projection, the monster exists only to be read: t e mOTlstrwTI is etymologically "that which re"eab," "that which warns," a glyph that seeks a

hieroph,wt. Like a letter on the page, the monster signifies something

other than itself: it is always a displacement, always inhabits the gap be{'w'een the time of upheaval that created it and the moment into which it

is received, to be born again. These epistemological spaces between the

monster's bones are Derrida's familiar chasm of difft!ranc(~: a genetic uncertainty principle, the essence of the monster's vitality, the reason it always rise from the dissection table as its secrets are about to he revealed

and vanishes into the night.

Thesis \I : The Monster Always Escapes

t(r:: Pl::. r

I l' I o~

We see the damage that the monster wreaks, the ~erial remains (the

footprints of the yeti across Tibetan snow. the bones of the giant stranded

011 a rocky LifO, but the monster itself turns immaterial and vanishes. to

rrappe(\[ someplale d:.c ( for who is the ydi if not fhl:' medieval Wild

mall? Who is the wild man if not the bibh al and cia kal giant?) . 0

matter how many times King Arthur killed the ogre of Mount Sa iot

!'vi ich,\cl, the mon tel' reappeared in annthl'r heroic chronicle, bequeathing t he Middle A e. an abundance of I1wrlr d'Arlllllrs. Rcgardl e of how

many time, Siguurney v'l;eaver·.\! beleaguered Ripley utterly destruy~ the

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 4.

hnp://site.ebrary.coml/ihlbrooldynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=19

--:::j::::",

"'» 1:-+--------~

~ Lde,.--

I\v...

C'\NYlJ tor ~ 5

~

Mode "

L IrEf' ?

~

~

Monster Cult lITe l$e\'cn

b e~es )

5

ambiguous Alien thal stalks her, its monstrous progeny return, ready

to stalk again in another bigger-than-ever seque\. No mDnster tastes of

death but once. The anxiet)' that condenses like green vapor into the

form of the vampire can be dispersed temporarily. but lhl." revenant by

definition returns. And so the monstcr's body is both corporal and incorporeal; its threat is it.s propensity to shift.

Each time the grave opens and the unquiet slumberer strides forth

("come from the dead, I Comc back ro teU you all" }, the mes~age proclaimed is transformed by the air that gives its speaker newlife. Monsters

must be examined within the intricate matrL1( of relations (social, cultural. and literary-historical) that generate them. In speaking of the new

kind of vampire invented by Bram Stoker, we might explore the foreign

count's transgressive but compelling sexuality. as subtly alluring to

Jonathan Harker as Henry Irving, Stoker's mentor. was to $toker.J Or we

might anal)'7c Murnau's self-Ioathin a Iopriation of the same demon

in Nosferarll. where in the face of ascent fascism t e undercurrent of

ELl"",t\-ti ()!>J

desire surfaces in plague and bodily corruption_ AnIle Rice has given the 1__-4~----------1

myth a modern rewriting in which homosexuality and vampiri.sm have

been conjoined. apotheosized; that she has created a pop culture phenomenon in the process is not insignificant. especially at a time when

gender as a construct has been scrutinized at almost every social register.

In Francis Coppola's recent blockbuster. Bram Stoker's Draw/a, the homosexual subtext present at least since the appearance of Sheridan Le Fanu's

lesbian lamia (Cam/ilia, 1872 ) has. like the red corpuscles that serve as

the film's lcitmotif, risen to the surface, primarily as an AIDS awareness

that transforms the disease of vampirism into a sadistic (and very medieval) form of redemption through the torments of the body in pain_

No coincidence, then, that Coppola was putting together a documentarD

on AIDS at the same time he was working on DmCIIlcl.

In each of these vampire stories, the undead returns in slightly different clothin • each time to be rl'ad a ainst contemporary . oeial move- \\...15 IS ~

D£.s

ments or a pccj/ic, determinin event: l decadence and its new possibilities, homophobia and its hateful imperati\'e~. the dcceptnnce of new

subjectivitic.-s unfixed by binary gender. a fin de sit'c,le social acti~

palernali$tic in its embran'. Discourse eX1:racting a Iran ..cultural. transtemporal phenomenon labeled "tht' vamptre" is of rat.her limited utility;

even ifvampiric figurlo?s are found alI1lQ~t worldwide, from ancient Egypt

to modern Hollywuod, each reappearance and its analysis is still bound

c

Cohen. Jeffrey J.(Editor}. Monster Theory: Reoding Culture.

Minneapolis. MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 5.

hnp:llsite.ebrary.comlliblbrooklynlDoc?id= I 0 151042&ppg= 20

~I~

6 Jeffrev Jerome C!)hcn

in a double act of construction and reconstitution.' "Monster theory"

must therefore concern itself with strings of cultural moments, connected by a logic that always threatens to shift; invigorated by change

and escape, by the impossibility of achieving what SUs.<ln Stewart caUs

the desired "fall or death, the stopping" of its gigantic subject,. monstrous interpretation is as much proces · as epiphany, a work that must

content Itself with lragments (footprints, bones, taiiSmans, teeth, shadows, obscured glimpses-significrs of monstrous passing that stand in

for the monstrous body itself).

Thesis III: The Monster Is the Harbinger of Category Crisis

The monster always escape~ because it refuses easy categorilationJPf the

nightmarish crcature that Ridley cott brQught to life in Alien, Harvey

Greenberg writes:

It is a'Linne~n nightmare. /Iefying e\·ay natural 13"'· of evolution; hy turns

bivalve, crustacean. reptilian,llnd humanoid. It ~eems carable oflying

dorma.nt within its egg indefinitely. It shrds its skin like a l;naJ;.e. its arapacc

like an arthropod. It deposits il ·oung into other species Like 3 wasp .... It

re~p()nd a cordin to Lamarckian (111.. ar~'·ln1an rinei le~. '

This refusaJ to participate in the cJ;lS. ificalory "order of thi_ngs" is true of

mon ster generally: the ' are disturbing hybrids whose externally incoAerent bodies n:si.~t attempt\; to include th em in any ~ystematic structuratiofl. And .'>0 the monster i" dangerous, .1 form suspcndl'd bet\ een

forms that threatens to ~111'1.~h dt ~ tlllctions.

Because or JI~ ontoJogicallimin.llity, the t'tlonster notoriousl y appt':lrs

at time:. oi crisis as ;) k.ind of third tl"fm that prohlematizes the dash of

extreme\-.I, "thai whidl qut'i>tions binary thinking and introdu s a

crisi.s:· This power to evade anclto undermilw has cour~ed through the

rnonstt'r·~ bllood from ddssical times, wlll.'l1 dt'spite all the attempt, of

Ari,totle (and later Pliny, Augustine, and L~idore) to inLOrporarc the

mon:-.trou~ rd"e~- into a cuhl'rt'nt epistemological s tem , the tllonster

alwa}'~ escaped to return to it, habitations at the margins of the world (3

purel\' I.: oncertuallocus rather than a geographic one).' Cl~ss ic.ll"won­

oer hook~·· r.)diLalh unJamim: th Aristotelian taxonomic w~tcm. for

by refusing an CJ,\y lllmpartmcntaliza tinn or their mon~trou s O llt~'IItS.

th{'}' dem.IIlJ .1 r.JJi~,ll rethinkillf! (If bound<uy .md lIormaJity. The toopreli~e;: laws of nature as set forth by science are gll'l'fuUy violated in

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Thecry: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University o/Minnesota Press, 1996. p 6.

hrrp://site.ebrary.coml/iblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151042r!r.ppg=21

Mon,lcr Cullme (

\'en Th

'S

)

7

the freaki~h compilation of the monster's body. A mixed category, the

monster re~ists an)' clas:.ificatioo built on hierarchy or a merely binary

opposition, demanding instead a "!» 'stem" aUowing polyphony, mixed

response (difference in sameness, repubion in attraction), and resi~tance

to mtegratlon-,Illowing what Hogh.: has called with a wonderful plin "a

deeper play of differences, a nonbinary polymorphism at the 'base' of

human nature."The horizon where the monsters dwell might ",'ell be imagined as the

visible edge of the hermeneutic circle it.self: the monstrous offers an escape fTom its hermetic path, an invitation to explore new s irals. new

an tnterconnec l' . met 0 so perceiv~g the world. 'O In the face of

the monster, sCientific mqUlry and its ordered rationality crumble. The

monstrous is a genus too large to be encapsulated in any conc...............LI...Ol.~_

<:.n~S Jo 10 c) ~

tern; he monster's very existence is a rebuke to boundary and enclosure; t\ON; J"t;.

(~

<.""11 kr f Gt-- tlike t e giants 0 Mmtdevil/e's Travels, it threateilS to devour «all raw &

e,vey... ?O I t-quyk" any thinker who insists otherv.;se. The monster is in this way the

living embodiment of the phenomenon Derrida has famously labeled

d~~ ~kM.~~..'\ ~

the "supplement' (ce dangereu:..: slIpplbnenc):~i it breaks a ar

c-~~e.s.

"either/or" sy logistIC OglC WIt a . nd. of reasoning closer to "and/or."

introducing what Barbara Johnson has called' a revolution to the vcr)'

logic of meaning."'~

Full of rebuke to traditional methods of organizing knowledge and

human experience. the geography of the monster is an imperiling expanse, and therefore always a contested cultural spoKe.

Thesis IV: The Monster Dwells at the Gates of Difference

The monster is ifference made flesh, come to dwell among liS. In its

function as dialectical Other or third-term supplement, the monster is

an incorporation of the Outsidl" the Beyond--of all thllC;

. that are

rhetorically placed as distant ,lOd distinct bu riginate Within.

01' i.llterity can be inscribed across {constructe throll~ I t e monstrous

bod I, but for the mosr part mon~rrous difference tends to be cultural.

political . racial, economic, l'xuai.

The cx.lp;geration ot <ultural difference into monstrous i.lberration is

Familiar enough. The most famous distortion o(cur~ in the Bible, wlwn'

the aboriginal inhabitants ()f nil3n are envisioned as menacing gi.mts

to justify the Hebrew co\onizJt ion of the Promised Land (Numbers 13 :.

Representing an anterior culture as monstrous justi/k~ its displacement

Cohen, Jeffrey J. (Editor) . Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 7.

http://site.ebrary.comIIiblbrooklynlDoc?id=l0151042&ppg=22

8

leffrev Icromr Cohen

.

CCN~ V\E:S-r

N~ e Q...A-flv'tiS

or extermination 5y rendering the act heroic. In medievaJ France the

ciJatlsons de ge~te celebrated the cru s.ade~ by transforming Muslims into

demonic caricatures whose menacing lack of humanity was readable

from their bestiaJ attributes; by culturally glossing "Saracens" as "monstra," propagandists rendered rhetorically admi~5ible the annexation of

the East by the West. T IS represena lona proJec was part of a wbole

olchonary of strategic glosses in which "monstra" slipped into significations of the feminine and the hypermasculine.

A recent newspaper article on Yugoslavia reminds us how persistent

these divisive mythologies can be, and how they can endure divorced

from any grounding in historical reaJity:

A Bosnian Serb militiaman, hitchhiking to Sarai.:v(), tells a reporter in all

earnestness that the Muslims are feeding Serbian children to the animals

in the zoo. The slOTr is nonsense. There aren't any animals left alive in the

Sarajevo woo But the: militiaman is con\'inced and can re':dll all the ''''Tongs

that ~fuslims may or may not have perpetrated during their 500 years of

rule.'

In the United States. Native Americans were presented as unredeemable

savages so that the powerful political machine of :"v1anifest Destiny could

push westward with disregard . Scattered throughout Europe by the

Diaspora and steadfastly refusing assimilation into Christian society,

Jews have been perennial favorites for xenophobic misrepresentation, for

here was an alien culture living. working, and even at times prospering

within vast communities dedicated to becoming homogeneous and

monolithic. The :vtiddle Ages accused the Jews of crimes ranging from

the bringing of the plague !() bleeding Christian chiJdren to make their

Passover meal. Nazi Germany simply brought these ancient traditions of

hate to their conclusion, inventing a Final Solution that differed from

l'ariier persecutions only in its technological efficiency.

PoliticaI or ideological difference is as much a catalyst to monstrous

repre~entation on a micro level as cultural alterity in the macro~Qsm. A

politicil figure suddenly out of favor is transformed like an unwilling

participant in a science elCperilllent by the appointed historiam ~)f the

replacement rt'l:!ime: "monstrous history" is rife with sudden, Ovid ian

metamorphoses. from VI ad Tepes to Ronald Reagan . The m o ~t .

trious of th e propaganda-bred demons is the English illS Richard 1 I,

whom Thomas More famously described as "little of sta

Cohen. Jeffrey 1. (Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneopolis. MN. USA : University ofMinnesota Press. 1996. p 8.

hnp://site.ehrary.com/liblbrooklynlDoc?id=IOI51042&ppg=23

~--------~----

~l~cNp6~

I

\lon~t("r Cultur ~

~

( cw n The ,

9

of limmes, croke backed, his len shoulder much higher then hi s right,

hard fauoured of ~ isage . .. . hec came into tht~ worlde with feete forward, ... aJso not "ntothed. ' 1 ~ From birth, N10re declares, Richard

was a monster, "his deformed bod)' a readable tex, "15 on which was ill~cribed his devinnt morality (indistinguishable from an incorrect politi(

cal orientation) .

The almost obse5~ive

. on Richard from Polr dor Vergil in

the Renaissance to the Frien S 0 Richard II11ncorPQrated in Qur own

era demonstrates the process of "monster theory" at its most actjve:~l­

lure gives birth 10 a monster before our cyes, aintin On:r Ihe normally

proporlione Richard who once lived, raising his shoulder 10 deform

simultaneously person, culturaJ response, and the po~sibilit)' of obje<tivity.'~ History itself becomes a monster: defeallUring, seLf-deconstruct ive,

aJwa)'s in danger of e},:posing the sutures that bind its disparate elerne.nts

into a single, unnatural body. At the same time Richard moves between

Monster and ~1an, the disturbing suggestion arises that this incoherent

body, denaturalized and always in peril of di ~ aggregation, may weU be

our own.

The difficult project of constructing and maintaining gender identities elicils an array of anxious responses throughout culture, producing

another impetus to teratogenesis. The woman who oversteps the boundaries of her gend'sks becoming a Scylla. Weird Sister, Lilith ("die

erSle E, a mer obscure" ), - Bertha Mason, or Gorgon .) " Deviant"

sexual identity IS snnt ar y su~ceplible to monsterization. The great medieval encyclopedist Vincent of Beauvais describes the visit of a hern~phroditic cynocephalus 10 the Fren.s:h court in his SpecululII Mi"iiralc

(31.126 ). 1 Its male reproductive organ is ~Jid to he disproport ionately

large, but the monster couJd use either sex at its own di.scretion, Bruno

Roy writes of this fantastic hybrid: "What warning did he come to d eliveT

to the king? He came to bear witnt'~_ to sc"xuai norms .... He embodj!\d

the punish;;;ent earned by tho~t: who "iolate .~exual taboos:' Z(! Thi s str-angc

creature, a compo~ite of the supposedly di~actc catego r ic "male' and

"female, 1 arrive betMe King LHUis to validate helt:n ,'(ualily over homosexuality, with It s SUppOSI:J inversions ,mel tran formations "Equ. fit

equu"," one lalin writer dt.'dJred; "The horse Decom a marc").' ) T he

strange d()~·hcaded monster is 3 living t:x(oriation r gender ambiguity

and sexual abnormality, as Vincent's cultural mo ment defint,. them:

heteronormalization incarnate.

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA : University of Minnesota Press, 1996. p 9.

hrrp://site.ebrary.coml/iblbroo/cJyrr/Doc ?id= 10 151 042&ppg= 24

\1).

~/\\L

<-II

~

(O'"\~I~

---

l\

~rSlf f\l\VL"~\

") ,,0

I\.e.

('l\.1Yt\ I{r ? S

"'-.M1

f 1<) ~

10

..

..c

>001

c"l:

~

C 0

(II

- u

"i.i!

u.o

:I

(II

-g,g

15.8:

OIl

(II

L- L-

G> 0

.0.

o~

c:)

>oL(II

G>

~-g

. :1

II

: E

I!

8.

J!!.,

..cG>

01 III

;::1

=LC(.-

.I!!

!lili.

9

., G>

~ ~

-f

Do.

G>_

(II

.. Lo G>

.,..c

G>

~\

III

c=

coO

-

:I

~c.

..e

o~

~

~

., E

L~

....

(?

.;::

.,

. .,

11)-

q::-

~

:)-

V

mE

m

L-

'L

..

-~8.

-.):1

<Q

:- 0

.. ..c

..co!:

~

~~

~ E .

o L-

~

O.g~

-

q:-

:j

:1

-

)dfrq I•.>romt· oh('n

From the c1assi.:al period into the twentieth century, race has bee

almoSI as powerful a catalyst to the creation of monsters as cuhurt:'. gen

der. and sexualiry. Africa t'arly hecame the West's si~nificant other, the

sign of its ontological difference simpl ' being skin c.olor. According to

the Greek m),th of Ph,leton, the denizens of mpterious Clnd unc~·rtain

Ethiopia were black because ther had been scorched b~' the too-do!'; e

passing of the sun. The Roman naturalist Pliny assumed nonwhite skin

to be ~rmplOmatic of a complete difference in temperament and attributed Africa's dukness to climate; the intense hl\lt, he ~'lid, had burned

the Africans' skin and maltormed their hodies Na tural Histor}\ 2.80 ).

These diffcrl'n .." . .

oralized through a pervasive rhetoric

of de·' ceo Paulinus of Nola, a weC] hy landowner turned earl)' church

homi I

IOpians had been scorched by sin and vice

rather than by the sun, and the anonymous commentator to Theodulu;';

ITitluenflal Ecfoga ltenth century i succinctly glossed the meaning of the

word Ethyopium: "Ethiopians, that is, sinners. Indeed, sinners can rightly

be compared (0 EthiopialiS,~ho are blaCk men presenting a terrifying

;ppearance to those beholding them."~! Dark skin was associated with

the fires of hell, and so signified in Christian myt:lOlogy demonic provenance, The perver!>\? and exag~erated sexual appetite of mon~ters generally was qUickly affixed to the Ethiopian; this linking was only stren~tlh. .ened by a xenophubic backlash as dark-skinned people were forcibly

imported into Europe early in the Renaissance. Narratives of miscegenation arose and circulated to sanction official policies of exclusion; Queen

Elizabeth is famous for her anxietv over "blackamoorcs" and their supposed threat to the "increase of people of our own nation,""

Through all of thl'~c monsters the boundaries between personal and

~gLJw.ail!rul.lO~-I*f:,.:.w'H;lIffi'~n:'tI,fe-tft1·I5-t:·~,~o ry co n fu sion fu rt he r, one

kind of alterit~, is often written as another, 50 that national difference (for

erence. Giraldus Cambren is

, imp e) IS trans or me

demonstr atcs just thi5 slippage of the foreign in his Topogmph)' of Ireland;

when he writes of the Irish (ostensibly simply to provide information

about them to a curious Engli h court, but~tu.IU y as a first st p I ward

invading and cololllZing, the i~nd ), he observes:

j (\

I t i, indeed a mmt filth y ra e, a ['Jce ~unk in viet', a race mort' i nOrdJlt

than all other n<l tions of th e Ii , I prin ' i plc:~ of f~ ilh .... The e people who

have cu ~ tom 0 d il l:rt'nl ( rom Olht' rs, ;lnd ~() op 0 ite. to lh t' m, o n mak-

ing signs either with tht' hands or the head, bf'(k n when they mean that

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor), Monster Theory : Reading Culture,

Minneapolis, MN. USA : University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 10.

hnp://site.ebrary.comlliblbrookiyn!Doc?id=I0151042&ppg=25

t..-

11

Tht s)

11

One kind of inversion becornt:s another as Giraldus deciphers the alphabet of Irish culture-and reads it backwards, against the norm of EJlglish

masculinity. Giraldus creat.:s a vision of monstrous gl::nder ·( aberrant,

. demonstrative): the violation of the cultural codes that valence gendered

behaviors creates a rupture that must be cemented with (in this case) the

binding, corrective mQrtar of English normalLy. A bloody war of sub ,.

jugation followed imml:diately after the promulgation of this text, remained potent throughout the High Middle Ages. and in a way cc)Otinues to this day.

Through a similar discursive process the East becomes feminized

(Said) and the soUl of Africa ro\"\'s dark (Gates) .~' One kind of difference ecomes another as the normative categories of gender, sexuality,

national identity, and ctbOlCIty shde to ether like the imbricated circles

o

. , CI jecting from the center that which ecomes

the monster. This violent foreclosure crects a self-validating, Hegelian

master/slave dialectic that naturalizes the subjugation of one cultural

body by another by writing the body excluded from personhood and

agency as in every way different, monstrous. A polysemy is granted $0

that a greater threat can bt, encoded; multiplicity of meanings, paradoxjcally, iterates the same restricting. agitprop representations rhat narrowed signification performs. Yet a danger re~ide in this muhipiic<ltion :

as difference, like a Hydra, sprouts two heads where one has been lopped

away, the possibilitie of escape, resistance, disruption arise with more

0~e c,ir:~tten at great length about the real violence these

debasing representations enact, connecting monstl'ri.ling dcri~tion with

the phenomenon of the s pe~oat. Monsten are never created ex 11;11;[0,

but through <l proce 's of fra,g mentation and reco

I! cmcnts arc t'xtracted " from various form:." 'Jinciuding- indl'ed, espe-

Cially marglO.llited :SOCIal group -J and then assembled as the monster,

"whi h can then claim an independent identitv.":" le politic;ll-cultural

monster, the emhodimelll of r.ldical difference, paradoxically thr~atens

to erase diiYerence in the world of its creators, to demon trate

Cohen, JeffreyJ.(Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN, USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 11.

http.-!/site.ebrary.comIJiblbrook/ynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=26

the potentia.! for the s)'stem 10 diffn from its own difference, in other

words not to be different at aJl, to ccase to exist as a sy~tt:m .... .Qi.ffr.rwce

that exi~l'. out 'de

. J\!veals the truth of

t f w~lem, its rdativity its fragilil)" and its mortali\\ .... Despite \\'hat il,

~aid around us p!"rsecu[Or~ are never obsc~~cJ with difference but rather

by its umlttcrab'lc contrarY, the lack of differena.-·

~~

By revealing that difference is arbitrary and potentiaHy free-floating,

mutable rather than essential, the monster threatens to destroy not just

individual members of a society, but the very cultural apparatus through

which individuatity is constituted and allowed. Because it is a body

across which difference has been repeatedl}, written, the monster (like

Frankenstein's creature, that combination of odd somatic pieces stitched

together from a community of cadavers) seeks out its author to demand

its raison d'etre-and to bear witness to the fact that it could have, been

constructed Otherwise. Godzilla trampled Tokyo; Girard frees him here

to fragment the delicate matrLx of relational sy;tems that UnIte ever

private bod" to the u Ie wo

=

Thesis V: The Monster Polices the Borders of the Possible

L

c(~

J!!

ui1i

The monster resists capture in the epistemological nets Qf the erudite,

but it is som_ethin

_. _a Bakhtinjan ally of the popular. From its

positton at the limits of knowing, e monster stands as a warnin

against exploration of its uncertain demesnes. The giants of Patagonia,

the dragons of the Orient, and the dinosaurs of Jurassic Park together

declare that curiosity is more often punished than rewarded, that one

is better off safely contained within one's own domestic sphere than

abroad, away from the watchful eyes of the state. The monster prevents

mobili ty (intellectual, geographic, or sexual), delimiting the sodal spaces

through which private bodies may move. To step outside this official

geography is to risk attack b}' some monstrous border patrol or (worst')

to become monstrous onesdf.

:c 8

a: ~

.!~

°1II.e

CD

CD III

c::=

c::..Q

~

::J

:I: a.

..E

.... CD

0.e

~

III

L

~

e

....

~c::

c:: 0

::I~

III

.1/1

IP~

OlE

01 L

.... CD

~a.

~~~

1::5

t»~

1: ~

~ E .

o

L

~

ooE.!!

l:~~[~~~ze first werewolf in weste.rn literature, undergoes his lupine

osis ..5 the culmination of a fable

. ,- r .~ Ovid relates how the I'rimeva giants attempted to plunge the world into anar(hy by wrenching Ol>' mpus rrom the gods, ~'nly to he shattered by divine

thunderbolt5. From their scattered blood arose a race Qr men who (00timl<.'d their fathers' malignant w .1'1 Among this wicked progeny wa.s

Lycaon, king of Arcadia. \\lhen Jupiter arrived as a gUt'~t at his hous~,

Cohen. Jeffrey J(Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Pres3, 1996. P 12.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=27

\Ionster Culture ( even These 1 13

Lycaon tried to kill the ruler of the gods as he slept, and the nexl day

served him pieces of a servanl's body as a mt'al. The enraged Jupiter

punished this violation of the host -guest relat,ionship by transforming

Lycaon into a monstrous semblance of that lawlcs~, godles~ ~[a!l' to

which his actions would drag humanity back:

V I'b 1

~~""

0

f-..

dJMe/\tIJ

~/f /l)~

~~~~~;:u-.u..u.;''.:....u.

' ':-lt~error

and. gaining the fields, howls dloud, attern tmg in vain to speak. HI.. nouth of it$elf gathers foam, and with his

at

or 00 e tums against the sheep. delighting. till in

slaughter. His garments change to haggy hair. hi~ arms to legs. He turns

into a wolf. and yet retains some traces of his fonner shape. lU

(,? 1)N

Jl~

1-<)

Cl t..JtI \ .(. '=?

The horribl y iascinating loss of L caon's humanity merely reifies his preprtSe fV1 ~r

vious moral state; the king's body is rendered all traml'arencc, instantly ~\A

~IV\ ";)f'V

and insistentl~· readable. The power oi the narrative prohibition peaks in

..I' 'f-~(/~/l (~

the lingerIng de5criptTon of the monstrously composite Lycaon, at that

median where he is both man and beast, dual natures in a helpless tumult of assertion. The fable concludes when Lycaon can no longer speak,

only signify.

\'\,lhereas monsters born of political expedience and self-justifying na- ~ bk,.r~ ~.,

tionalism function as liv;ng invitations to action. usually military (inC? \ ~

?C.",-d'<)

vasions, usurpations, colonization., i, the monster of prohibition p(llices

vS~

the borders of the possible, interdicting through its grotesque bod}' some

Ot'\~ ~ 1\1JJbehaviors and actions, envaluing others. It is possible, for example, that

,~

medieval merchants intentionally disseminated maps depicting sea ser'J c \.i "'-.\

pents like Leviathan at the edges of their trade routes in order to d,iscourage further exploration and to establish mono alit'S." Every monster IS In t IS way a double narrative, two living stories: one that describes

how the monster came to be and another, its testim

,hat

cultural use the monster serves. The monster of prohibition exis to

demarcate the bonds that hold together that system 0 rc atlOns we call

culture, to call horrid attention to the harders that cannot-must nOIbe cros~cd.

Primarily these borders arc in plalt' tu control the traffic in women, or

more generall}' to " tahlish strictly hnmosncial b'!10!!ln!.Q!~W-1fW.!~~feeft]

men that keep a patriarchal society functional. A. ind of hl'rdSllH! 11 , thi

monster delimits the socinl sp.lce through which ell tur.l

move, and in classical timl's (for example) validat d a ti~hr, hier;lrchica'l

system of naturaliLed leadership and mntroi where every man hat.! a

r

Cohen. Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN, USA : University o/Minnesota Press. 1996. p 13.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbrook/ynlDoc?id= 10151 042&ppg= 28

.

PJ~S ~

I.-

<...ve J /l~ J ~

2

a--

"

~I"'r

14

Jeffr~y

Jerome Cohen

"geographic" monster is Homer's Polv hemos. he quinte ential xenop obic rendition of the foreign (the barlwric-that which is unintelligible within a gi\'cn cultural-linguistic system ),J) the C)lclopcs are represented a~ S:3vag~~ who have not "a law to bkss them" and who lack the

tec/lIle to prociu(c (Greek-style ) civilization. Their archai~m i~ conveyed

through their Ilack ofhierafl:hy and of a poiiti(s of prelxdent. This dissC'lciation from communit}" It'ads to a rugged Il1dividuali~m that in Homeric terlTl~ can only be horrifying. Be ause thl'y liv(, without a ~y~t('m of

tradition and custom. the Cyclopes arc a danger to the arriving Greeks,

men whose identiti.:s arc contiJlg<::nt upon a compartmentalizl'J functiun within a deindividuaJizing s stem of .subordination and control.

Polyphemo ' vi..:tims are devoured, engulfed, made to vanish from th~

public gaze: cannibalism as incorporation into the wrong cultural hod\'.

The monster is a powcrful ally of what Foucault calls "the society of

the panopticon ," in which "polymorphous conduct [are] actuaUy extracted from people's bodie and from their pleasures ... [to be I drawn

out, revealed, isolated . intensified, incorporated, by multifarious power

device ."" Susan Stewart has observed that "the mon~ter's sexuality take·

on a separate liko"; Foucault helps us to see why. The monster e mbodi~s

tho e ., llal practi~l" that must not be C0 l11mit1ed, or that ma' b COI11mlttc on y thr~ugtl the hQdll of the monster. "e and Th el/1!: the monster enforces the cuitural cod(.'~ th.lt regulate . xual desire.

Anyone familiar with the lo"... -hudgct seiencc fiction movie Cfaze of

the 19C;1)~ will recognir_e in the preccd.ing . emcoec two ~uperb films of the

genre, one about d radioactive virago fr m outer space who kilb every

Illan she loudles, the othl'[ a ocial parable in which ,iant ants (rea ll",

Communist · burrow beneath Lor Angeles (that is, HolIywo(ld and

threatcn world peace (that is, Ameri can onscrvatism). I wnnect the e

two . I.'eminglr unrd<lted titl ~ ' here 10 call attention to the anxieties that

rnonsterized their suhiccts in the tlrst place, and to enact yntacticallyan

even deeper fear: that the two will ioin in some unholy miscegenation.

We; have cen thot the monster ari ::.t. oJt the gap where diffcrt'J1ce i perceived a dividing a recordin~ voi from it captured ~ \Ihject; the ~ ­

rion of th i~ di vi::.ion is Jrhitr;lrv, ;1110 ,m rail ' 10: frulll JIMtom or ... I<il!

co or to re IgIOU~ WIt: , (\I ~tOIT1, Jnd political ideology. The mOI1,ter \

d , ~tructiq:ness is rea lly a de o nstructivene~~: it tnreJh'OS to revl',JJ t'hat

difference origillal(' ~ in proc('~s, rather than in fact (alld that "Ial.\" is

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University o/Minnesota Press, 1996. p 14.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151 042&ppg= 29

~

~ehuM;rv-e­

'::>T C(M.I\~ 7S'

-h

(V1W1sr f'lvt .s.

subject to constant reconstruction and changel. Given that the n.:'(urders

of the history of the West have been mainly European and male, womell

( Sire) and nonwhites cnJelII.' have found themselves rept'dtedly transformed into monster:;, whether to validate spel..' ific a1ignm~nr~ of mascliTinlty and whnen~ss, or simply to be pushed from its rcalm of thought.

Feminine and cultural others are monstrous enough hy themselves in

patriarchaJ society, but when they t'hreaten to mingle, the entire economy of desire comes under attack.

As a vehicle of prohibition, the

st often arises to enforce

e ·ncest taboo (wh · h e~tablishes a traffic in

the laws of exogamy, bot

women by mandating that rm:':'\'-I~-ff'-\H'1!ITS

crees against interracial sexual mingling (which limit the parameters of

that traffic by policing the boundaries of culture, usually in the service of

some notion of group "puriry").J7 In(est flarrati\·~s are common to every

tradition and have been extensively documented, mainly o\ving to LeviStrauss's elevation of the taboo to the founding base of patriarchal society. Miscegenation, that intersection of misogyny (gender anxiety) and

racism (no maner how naive), has received considerably less critical attention.. I will say a few words about it here.

~.w:~........::..u..;I..lst....!J~o.ng been the primary source for divine decrees against

e of tht.'~e pronouncements is a straightforward

that comes through the mouth of the prophet

Joshua (Joshua 23:12ff.); another is a cryptic episode in Genesis much

elaborated during the medievaJ period, alluding to "sons of God" who

impregnate the "daughters of men" with a race of wicked giants IGenesis

6:4). The monsters are here, as elsewhere, expedient representations of

other cultures, generaJi~ed and demonized to enforce a SHict notion of

-group sameMt'S$. Hie tears of contammation, impurity, and los' of iden tity that produce stories like th..:. Genesis episode are strong, and they

rearpear ince~~antly. Shakesp~are's aliban, for e ample, is the product

of slIch an illicit mingling. the " fT(~ckled whelp" of the Algerian witch

Srcorax and tbe devil. h;lrlotte Bronte rt!\lcrsed the usual paradigm in

Jalle E.l're (white Rochester and lunatic Jam,IICan Bertha J\la~nn) . but

horror movies d~ seemingly innocent as King Kelllg demonstrate mi!>(,'genation anxiet I in itll brutal c scnce. Even a film a re ent as 1979 '5 im mensel). ucc.e ful Aliell ma), have a cognizance of the fear in it underworking.~: the gTotesque creature that . talks the beroine (dr

cd in the

flI1al scene only in her underwear) drips a glistening slime of K- Y Jelly

Cohen. Jeffrey J. (Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University of Minnesota Press. 1996. p 15.

http://sile.ebrary.coml/iblbrookJynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=30

(:

() -- v-S-

t

'0

0 ~ftMy.

~\)

S\ (\A W\.(L

oJ\..

t

L/'A-'"">

1-

J

f-

--...e. ~ I-

r-e-x:l

1WlN\

S'f"'"~l\-r'

nO--

16

le Art'} krom.: Cohen

from its teeth; the jaw tendons are constructed of shredded condoms;

and the man inside the rubber suit is Bolaji Badl!.io, .1 :vtasai tribesman

standing ~e\'en fCt't tall who happened to be studying in Enftland at the

time the film was cast. I~

The narratives of the West perform the

'~l dance around that

fire in whic miscegenation and its practitioners ave 'been condemned

to burn. Among t. e ames we see teo d women of Salem hanging,

accused of sexual relations with the black de"il; we suspect ther died

because they crossed a different border, one that prohihits women from

managing property and living solitary, unmanaged lives. The flames

oevour the kws of thirteenth-century England, who store children from

proper famili e' and baked sedt~r matzo with their blood: as a menaCl~ to

the survival of English race and culture, they were expelled from the

country and their property confiscated . A competing narrative again implicates monstrous economics-the Jews were the money lender~, the

state and its commerce were heavily indebted to them-but this second

story is submer cd in a harrie 'in fable of cultural purity and threat to

e

Christian continuance. As the American frontier expan e cneat

hanller 01 Mal11fesl Destiny in the nineteenth century, tales circulated

about how "Indians" routinely kidnapped white \"omen to furnish wives

for t hemseh'cs: the West was a place of danger waiting to be tamed into

farms, its menacing native inhabitants fit only to be dispossessed. It matters little that the protagonist of Richard Wright's Native 50/1 did not

rape and butcher his employer's daughter; that narrative is supplied by

the police, by an angry white so(iet)', indeed by We~tern history itself. In

the novel , as in life, the threat ocems when a nonwhite leaves the reserve

abandoned to him; Wright envisions what haprens when the hori7.0n

of narrative expectation is finnh ~d, and his ((1nclu.... ion (born out in

seventeenth-centurv Salem, medieval r.ngland, and nincteenth·ccntllTv

America) i~ that the aClUal circumstances of history tend to vanish wben

a narrative of mis.:cgenation can be supplied

r

The monster is transgressive, roo sexuall, perversely crotk, a lawbreaker;

.and so the mon'ter and all that it emhodies nm~ t be exiled or destrovccl.

The repressed, however, like Frcud himself, alway. St:CI11'" to return.

TheSIS VI: Fear of the Monster Is Really a Kind of Desire

The monster is w ntinually linked to forbidden practice, in order to

normalize and lo enturce. The monster also 'Itlract!>. The 'ame creatures

Cohen. Jeffrey J. (Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA : University o/Minnesota Press. 1996. p 16.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=31

II c.

"

>

re ~ l rV-v-

CLtI 1.AJ'

)

~Ion ster Culture (SevC'n The e» )

17

who terrify and interdict can evoke porent escapist fantasies; the linking

of monstrosity with the forbidden makes the monster all the more appealing as a temporary egre,~ from constraint. This simultaneous rcpulsian and attraction at the core of the monster'~~omFo~ition accQuijts

g;eatly for its (:onlinued cultural popularit,v, for the fact that the monster

seldom can be contained in a simple, binary di.uC:l;tic !,thesL5, anti!I)~·

.~is .. . no synthe~is'. We distrw;t and loathe the momter at thc same til '

we cnvy its freed(lm, and e h

al r.

T Hough the body of the monster fanta sies of aggression, domination ,

and inversion are allowed safe expre.ssion in a clearly delimited and permcmently liminal ~pace. F~Glpist delight give5 \,'J\' to horror only when

the monster threatens to over,;tep these boundaries, to destroy or deconstruct the thin wa lb of categorr and culture. When containl'd b geographic, generic or cpistemic marginalization, the momter can function

as an alter ego, as .10 .)lIuring projection 01" I an Other) sl'lf. "1 he mon~tcr

awakens one to the pleasures of the bod\·, to the simple and fleeting jo~'s

of b('ing fri¢1tened . or frightenmg-to the expcrience of mortalit~· and

corporality. We watch the monstroll~~ spectacle of the horror film becausc we know that the cinema is a temporary place. that the jolting sensuousness of the celluloid ima~l'~ will be followeJ b)' reentry in(Q the

world of comfort and li ght. '~ Likewisc. the. story n the page before us

may horri ty (whether it .Ippcars in the Nc;v }~Jrk Ti ll/('S news Clion or

Stephen King's latellt novel matters litt le), so long as we are safe in the

knowledge of ib ne.lring end (the number of pages in OUf ri!;!ht hand is

dwindling) nnd our lihcration from it. Aur,llly rc eiwd narratives work

no differently; no matter how unsettling the d ' riptio n of thr giant , no

matter how many unhaptized children and haple knights he devours.

King Arthur will ultimatt'h' dl'5tn1Y him. Thl' .H1dicncc knnw~ how the

Time!. or l·.unlQ] tempor.llly m.1rgi 1l.1 Ii/\.' t~t' mO ll If IUS, ut at the

lIme al (lW It .. ,aft' rt:.J m uf I.'xl'rc,sion and pay: on Hallow en

t'\'eryonl.' i~ a demon for a night. The same impuLc to at aractic fa nt;1!>),

is behind much lavi hi ' hiza rre manuscript rnarginaliJ, from abstract

scribblings al the edges of an ordt'red page to preposterous anim •.1 and

vag ut·ly humanoid cr<.:atllre~ I;lf str.lO '(; all :1I0nlY that crowd a biblic.ll

text. GM' yll'. and arn otdy sculpkJ g ro k:>'1ur~, lurking at th e a :,,he:mh or upon the roo . of tbe c.lIhcdr.1. like\,·i. 1? re rJ lh· libcr;) ting

fanrasirs of a bored or repn:s<;cd hanJ sudJ('nl~' frl'l'J to populate thL'

~.Ime

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis. MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 17.

http://site.ehrary.comlliblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151041&ppg=31

18

Ie

reI' Ieromc Coh.:n

margins. Maps and travel accounts inherited from antiquity i.nvented

whole geographies of the mind and peopled them with exotic and fantastic creatures; Ultima Thule, Ethiopia, and the Antipodes were the me-dieval equivalents of outer space and virtual rca.lit , imaginar (whoily

verbal) geographies acce ible from anywhere, never me.tnt to be discov-oo-ht~rtw:M·;::W"a1altrtrll!

b" explored. Jacques Le Goff has ,... ritten that

t e Indian Ocean (a "men al horizon" imagined, in the Middle Ages. tQ

be complete! eoda

}' land) was a cultural space

where taboos were eliminated or exchanged for other~. The weirdnc5 ot"

this world produccd an imprC'~illn of Iiher ation dnd freedom. The strict

moralit y impo~o:d by the Church W.I~ C;fln tr,lsted willi ti1~ dj ~((i'nfiting attract iveness of II world of bizarre tastes which wac! iced caprophaS¥ and

cannihaJism; of bodily innoce nce, where man, frefd of the mode t )' of

clothmg, rcdlscovered nudl~1ll .md ~ex-ual freedom; <Iud where, on e rid of

restnctin' monogamy and family barriers, he could give him~elf over to

polygamy. incest. and eroticism.

~A

.t:\ S '--\

N,

The habitations of the monsters ( ~ndinavia,Ameri~> Venus, the

Delta Quadrant- whatever land is suffic.iently distant to be eXQticized )

are more than dark regions of uncertain dangt'f: they are alsQ realms of

happy fanta~)', horizons of liberation. Their monster ' serve a~ ~econdary

bodies through which the po ·sibilities of other gendas, other sexual

practice , and other~o(ial customs can be explored. Hermaphrodites,

Amazons, ,lnd \.l'l.ivioliS cannibal beckon from the 'dg '-S of the world,

the mo <;!' distant planets of the g;tlax~'.

The co-optation of thl' mon~tcrj nto_a svmbol of the desirable i~ often

accomplj hed throu!\h the neutralization of potent i.lll ~· tbrt.'3tening as-=- -

causative fantn~i~'s even without thl'ir valcflCl' reveLed. \Vhat Bakhtin

calls "official culture" Can tral1:>l~'r all that i~ viewed a~ uncle irable in itself into thl~ hody of the monster, performing a ",i'ih-fuJfillment drama

of its own; the scapego3ted monster is pt'rhap~ rilU:llly destrored in the

course of some official narrative, purging the communit . by eliminating

its sins. The monster's eradi tion fun clions as an exorcism and, when

[('told ,lIld prolllulg.Jteci ..IS J cate hi m. The ll1on.l~tl(.llly manufactured

(J1It'SIt· del LlInt Graci! :.crvt'S a5 an t'e l(' s i a~ tiLdl\' .,.tnctiollt'd antidol<:' to

Ih 2 1nmer nlOrJlity 01 Lilt e ul. r romJn(e!-; when -SIr Bors com

a Col tie where "ladtl'S 01 lugh descent and rank," tempt him to l'xuaJ

Cohen, Jeffrey J. (Edilor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

MinneIJpolis. MN. USA : University ofMinnesota Press. J996. p J8.

hrrp:/lsile.ebrary.com/liblbrooklynlDoc?id=JOJ5J042&ppg=33

lI.\onstcr Culture (Seven Thescsj

19

indulgence, these ladies are, of (ourse, demons in lascivious disguise.

Vv'hen Bors refuses to sleep with one of these transcorporal devils (described as "so lovely and ~o fair that it seemed aU earthly beauty was

embodjed in her" , hiS steadfast a sertion of control banishes them aU

shrieking back to he.ll.·~ The episode valorizes the celibacy so central to

the authors' belief }stem (and so difficult to enforce) while inculcating a

lesson in moraHt\, for the work's intended secular audience, the knights

and courtly women fond of roman.::es.

Seldom, however, are monsters as uncomplicated in their use and manufacture as the demons that haunt Sir Bors. Allegory may flatten a monster rather Ihip, ~s when the vivacious demon of the Anglo-Saxon hagiog;aphi( poem Juliana becomes the one· ~ided complainer of Cyncwulfs

Elene. More often , however, the monster retains a haunting complexity.

The dense symbolism thai makes a thICk descflpllOn of thc' mODStCfs 10

Spenser, Mi lton, and even Beowl/lf so challenging reminds us how permeab~le the monstrous bod\' can be, how difficult to dissect.

This corporal fluidity, th' imultaneity of anxjely and de ire, ensures

that the man ter \\'ill alway dangerously entice. A certain intrigue is

allowed Co'ven Vincent of Beau\'3' , well-endowed cynocephalus, for he

occupies a textual PJce of allure before his necessary dismissa\' during

which he is ~ranlL-d ,In undeni.lhle charm. The monstrous lurks SOlTlewhere in that ambiguous, primal-space between fear and attraction, dose

to the heart of what Kristeva caU "abJection":

There looms, within abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being,

directed against a threat that ecm- to emanate from an exorbitant outside

or inside e'ected b nd th~' ope of the pos.')ible.thl' (olerahle, the thinkablc. It lies there , quill' close, but it cannol be imilated. Jt bcs.cl'".hl;!~,

worries, fa inale5 d ire, whi h, nonethekss, does not l, t it5('lf b~ ~educed.

Apprehensive d ire turns 'de; i :kened, it rej ~ct ' .. . But simulta11cously,

'just the ~ me, that IInpetu , tha i ~pasm, t1lalleap IS drawn toward an c'lsl?where a tem pting as it is condemned, ntlagginglv, like an ine~capahle

b o merang, 3 von e.x of ummon and repulsion place the one haunted

by it literall)' beside himself."

And tht' elf that one 13 n

o suddenly and ..0 nervously hesiclc is the

rnomtcr.

The monster i., the ab 't:'cted fragment that e.Hlbles the formation of

all kinds of idl'ntiti - pc onaJ, national, cultural, (;'(onomic. sexual,

psychologial, univer ai, particular (even if that "panicular" identity is

Cohen, Jeffrey J. (Editor). Monster Theory: Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 19.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbrook/yrrlDoc?id=101 51 042&ppg= 34

20

Icffrcv Jerome Coht!1t

an embrace of the power/staws/knowledge of abjection itself); as such

it reveals their partiality, their contiguity. A product of a multitude of

morphogenese (ranging from somatic to ethnic) that align themselves

to imbue meaning to the Us and Them behind every cultural mode of

seeing. the monster of abjection resides in that marginal geography of

the Exterior. beyond the limits of the Thinkable. a pIa e that is doubly

dangerous: simultanl!ou~l)' "exorbitant" and "quite close," Judith Butler

caUs this conceptual locus "a domain of unlivability and unintelligibility

that bounds the domain of intelligible effects," but points out that even

when discursively closed off. it offers a base for critique, a margin from

which to reread dominant paradigms.'· Like Grendel thundering from

the mere or Dracula creeping from the grave, like Kristeva's "boomerang, a vortex of summons" or the uncanny Freudian-Lacanian return of

the repressed, the monster is always coming back. always at the verge of

irruption.

Perhaps it is time to ask the question that always arises when the monster is discussed seriously (the inevitability of the question a symptom of

the deep anxiety about what is and what should be thinkable. an anx.iety

that the proce of monster theory is destined to rai se ): Do monsjer~

really exist?

Surely they must, for If they did not. how could we?

Thesis VII: The Monster Stands at the Threshold ...

of Becoming

0 (' I./Ve :> r€ ~~

l5

g.s~la.tJI(..W~+.aQU~~leJgc mi ne ,"

onsters are our chiJdren. T ey can be pushed to the farthest margins

o geography and discourse, idden away at the edges of the world and

in the forbidden recesses of our mind, but they alwJ)'s return. And

when the y come back. they bring not just a fuller knowledge of our place

in history and the hi "tory of knowing our place. but they bear selfknowledge. hllman knowledge-and a discourse aJI the more f1acred J~ it

arises from the Outside. These monsters as.k us how we perceive the

wor.ld. and how we have misrcl'n:~cnted what we have attempted to

place.. 'nleY ask us to recvaluate our cultural ~:-.umpti(ln~ about ran:.

gender, ~t:xllJlity, our perception of difference. our tolerancc toward its

t'xpression. They ask us why we have crt'aled them .

Cohen. Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN. USA: University o/Minnesota Press, 1996. p 20.

http://site.ebrary.com/liblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=35

f.,,1onster Culture (Seven Theses)

21

Notes

ess spirit th:1t unca.nnily incor-

monster.

~. I rea~ze that this ' an interpret rve biogr olphical maneuver Barthes would

surriy have C".J cd "the li\ .

3. Thus the superio . of Joan Copjec's "Va , pires, Bre.ast-feeding, and Anxiety;'

Qc/olm' 58 Fall 1991 ): l"- •

s Vampir<'s. Burial, ami Deatlz: Folklore

and Rcnlit),( Ne H ven. Conn.: Yale lIni v er 'ity Pre , 19 ).

4 . "The giant is represented thro ugh movement, through being in time. Eyen in

the a~cription of the lill landsc.ap 10 the giant, it is the activities of the giant. his

or her legendar . a 'on . that ave n.-sulted in the observable trace. In Cl)ntrast to

th~ ~till and pert< d uni ene of the mi iature . the giga ntic represents the order and

dburder of hi to rical fur ," Su an Stewart. On Longing: Nl1rmcives of II,,' '\iinillCllrc,

tll/: Gigalltic tlrt Souvenir. 1I.t' Call a ion (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Pre.,.\.

19 4) , 86.

~,Harve R. Greenberg.. "R imaging the Gargo Ie: P choanal}'1ic Notc~ on

Ali..,;." in Cia j' u'eo'IIIII!N: Film, f, mil/ism. mId cic Ire Fiction. ed. o nstJnC;c Prnle}·.

E.IiS.lbcth Ly n, 'n n pI cl. nd Janet Sa trom (MinnC'"dp 1i5: niver~it~· of Minnesota Pr . I I ). 9<l-9 1.

6. MlIrjori· arb r·juo.Ptl-lA(tT'

York: Routlt'dg • •

1. II .

she del3.nes as -3 f il ure:-;o~fooIII-~""'-="""':::T="""''1'<';;~=:=--:rr1''''''''==:-::::::::::-::

I Su (J pas..e be (}.I\R

~

.w....f-

(~In, ~ffVl e ~ ,""e..f;l L S

\Qel\~ ~

d~.

1'W~~~.s;;l.r.l¥~M~rpcr i"d.

T/'e A-tClllsrrOIl>' RI1(n in

mbridse: Hlrv.ud Univtr<iry Press. 1981).

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis, MN, USA.: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. p 21.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbroolclynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=36

22

Je[fr~\'

Jemme Cohen

molruus in the manufacture of

heuristi s is partially bas

"Tile Li its of Knowing: Monsters and

the Rrgulation of Medieva

," edii'vlIl Folklorr 3 (faJI 1994); t-.I .

9, Jerrold E. Hogle, "The Struggle for a l)iChoto m)': Al-io;clion in Jekyll :J.nd His

Interpreters:' in Dr. Jekyll alld Mr. H "(/c aft,., Olle HU/ldrrd Yellr , cd. William VecJer

and l;nrdon Hirsch (Chicago; Uni\'{' rsit-y of Chicago Press,1988), 161.

10. "The hc.rmc.neutic circle d es flQt permit a . ~ ('lr escape to an uninterrupted

realitr; but we do not ihavc to ! kt·cp going around in th~ ~;tmc path ." Barbara

HerrnSlem Smith, dBehrf and ReSistance; A Symmetrical A. nunt," Cnt;wl IlIquiry

18 (Autumn 199t ): 1.37-}8.

II. Jacqu{'s Derrida, Of Grllmmllt% g}" trans. Ga)"ltri Chak!:lVorty Spivak (B.1lti·

more; Johm Hopkin,. University Pre,s, 19i'-\ J.

12 . Barbara Johnson. "Introduction," in JacqLJo?"S Derrida, J)is;cmillutioll, trans.

Barbara John. on ( Chi ca~o : University nf Ch.icago Press, 1981 , xiii.

13. H. D. S. Greem\"dY. "Adver~ arie~ Create Del'ils of Each Other.~ BIlS/OIl (i/ohC',

December 15, 1992.1.

14. Thomas More, The 'till/' Editi{1rl of the Completi! Wo rk.!; ofTIlOmas Afore, v(\L 2,

The History of [(jng Richard III. ed. Richard S. Sylvester (New Haven, Conn.: Yair

Uni versit ), Pre..\" 1963), ;'.

15. Marj(lrie Garber, Shakespeare's Chast Wrilers: Ute-ra/llre as Uncanny Cau.laliry

(

('IV York; Rourlcdse. Chapman & Hall. 1988). 30. My discussion of Richard is

indebted to Marjorie Garber's provocative work.

In. "A portrJil !lOIY in the Society of Antiquaries of London, painted about 150" .

sh (l w~ a Richard with straight should... rs. But a second porlT it, po sibl (If ea rl ier

date, in the Ro}ra] Collection, eem to emblematize the whole co ntrover y (over

Richard 's sup po d mODStro il I. for in iI, X-ray exami na tion reveals a o PriSiR.al

straight shoulder line. which was .~ub5equenLiy p;linted over to present th e raised

rjht shoulder sllI'Ioueife so onen CQJlIt'd h)' later portraii:slf." Ibid., 35.

:;;>

17. I am hinting hcrll at the possibility of a fem inist recupcf3tion of the gendcrcd

monster by citing the titles of two famous books about Lilith (a favor ite figure in

feminist writing) : J cques Bril's Lililll, OU, La Mer£' obscurr (Paris: Pa),ot. 1981), and

Siegmund Hurwitz' Lilith. di£' mIt Em: Eine SlIidJe uber dUllkl1" Aspckre des \\ eib/idlC" (Zurich: Daimon Verlag, 1980 .

18. "The monster-woman, threatening to replace her angelic si ~t('r. embodies intran$igcnt female autonomy and Ihus represe nts both the autho r'. PI wer to alliJ}" his'

anxiet ies b . calling their source bad names ('\ritch, bitch, fien d. mUllster ) and m nuJtam'ou -I ,the m} teriou power of the character who refu. es to stay in her textILlU;'

ordained 'place' lind thus generate a stor), that 'gets aW"'oI ' from it. author." S,mdril

M. Gilbert and Susan uba r. Tile Mad" 'o" ",,, ill III A ll ie: ,/,/", W(llll11l1 IVril.:r IlIld tIle

NirrrrcenrIJ Cenltlrr U r£TCII )' /IIIa, JIlt/riOlI (New Haven, Conn.: Yale n i \l:I ~ it y Pre ,

1984 ), 211. The "dangcrou. " role of fen inin .. will in the engcndt"Ting of monst.? rs is

31 0 {"·xplored by Maric· H I~n e Hu t:t in !V((llUtro!l. !IItt/g;'Ultion (Ca mbrid l!~ Harvard

UniVersi ty Pre . 1993 ).

19. ,\ t .'noccph3Iu5. i a dog· headed man, like the r .·ntly de anoni zed Saint

Christopher. Bad enough to be a cynoeeph:J\us without being hermaphroditic to

J

Cohen. Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis. MN. USA: University ofMinnesota Press, 1996. p 22.

http://site.ebrary.comlliblbrooklynlDoc?id=10151042&ppg=37

1'"I()nsll'r CulLlJr~ ( eV(n T h ' e

23

boot: the mon leI accrue' one kind of diffm:nce on lOp of ;lI1othc:r, like a ma!!,ne!

that draw~ differenc " m tu an aggregate, multivalent identity ;)rollnd an ul151ablc

J

corc.

10. Br

to " ~ En marge du mondc connu: Le, races d~ mo ns.t ~," in ,"'.ife _ rI~

la mnrgl/lalltc, .

c. " .'

.

' . ,

~ .

. \.I rore ,

19T ), . "This tran sJJlion is minco

21. See, fur example, Monica E. ~l(AJpine . "The Pardoner's Homo,clCuality and

How It Math.' Ts," P.\1LA 95 (19 ): S-;1~.

22. Citro by Friedman, Tire MOirstrolls Rrm:s. 64.

23. Elizabeth deponed "blackamoor.:," in 1596 and again in 1601. See Karm

Newman , "'And Wa.sh th e Ethiop White': Femininity and th e Mo nstrous in Othello: '

in Shakespeare ReprodIlCt'd: TlJ I! Tw i" Hi;.( . , (md Jdeolag)'. cd. /can E. Howard and

Marion F. O'Connor ( }olC\,' York: ~·1eth n, 198 It 1 8.

2·1. See GiraJdus C.1mbrensi , Topograp'

. eT'Il(le ( The Hi;(ory a/ld Topography

Ireland ', tran~.lohn J. O'Meara (,-\t1antic Highlands, N.J.: Humanit ies Pre-so 198::), 2.!.

15. See Edward Said, Orientalism ( New York: Pantheon, 1978 ); Henry Lou.is Gates

Ir., Til Sigllify;"g .\,forlkey: A Theory o/Afro-Ame.ricall Literature (. ew York Oxford

University Press, 1988 ).

26. Rene Girard, Tire Scapcgool. trans. Yvonn~ Fr~cero fBaltimore: Johns Hopkins

Universil)' Prcs~, 1986),33.

17.lbid .. ll~ll.

28. Extended travel was dependent in both the ancient and m .. d.ieval world on the

promulgation of an idea'i or ho~piI3lit)' that ,anctified the respon :;ibility of host to

gut'st. A violation of that code is responsibk fClr the destruction of the biblic.1J

Sodom and Gomorrah. for t hc d. \nlution from man to ~iant in Sir Gawain and IIII!

Carl ()r Car/i~1 • and for the first punitive transformation in Ovid'" Metanrorphos(~f.

This POpyiar tYpe of mrpriYe mal' be '-oR""I~i"Rtlr 1;!l> .. leEi Ih .. faal", ef A~5~ilaliP.i!

such stories crwaJue the practice whose

1 mg t e dangerous behavior. The:' valorization is ac.(.omplishcd in one of two \Vap:

the host IS a monster already and learns a lesson at the hands of his guC$ t , or the host

becomes a monster in the our e of the nJrratin' Jnd :IUdiencc members realize how

rh C'y :.houlJ conduct th em~e h~. In either case. the c.!o.tk of monstrOli ne S c,all s attention to those behaviors an d aH itlldes the text . ~ conce-rn~d with into?rdicting.

29. Ovid, Me(a morpllo.es ( Loch I sical Librar y no. 4 l ), t'd. G. P. Goold (Ca mbridge: liarvard ' nivcrsit )' Pre , 1916, rpr. t9 ), 1.156- 6l.

30. Ibid., 1.1)1-39.

) I. I Jill indchtt:'d to Ke~rrun!! Hanft of liarvard L !liverslly for shJr:ng her rt's~arch on m"dkval map produ(rio l1 for thi s h 'Po th i .

32.. i\ u eful (a lbe it politicalJ ~' charged ) knll for wch a <-all ... tiv' i MJ,/IlUUUIIllt-,

"aJI-male group with asgr iOIl J one ma jo r fu n rio n:' C! Jo~eph H;lrri . "Love

alld Death in t hl' Mtmnerlllllld: An . sal' with pedal Re CITn cc to tht' BjeJrkomtl I a nd

Tilt' RalT lr 0/ 'raldoll." in H rro i(' POClr)' i ll l h ~ Arrglo- ·,r.x01l {Jalali, o?d. Helen Da mi 0

.md I., h n u:y rk ( Kal ama1 0: i\kdit val ImlitutdW tern M ichi ga n , t at

niverir .199) ). 78. Sec al 0 th IIHI'Nmpw di s~us in n of "Mcdicval Ma~ u ILnirie.'i,·' moderateu and edited by Je ffre)' Jerome Cohen. 3c(l'ssiblc via \'II'\'l/W: http://www.george-

"I

Cohen. Jeffrey J.(Edilor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis. MN. USA: University o[Minnesola Press. 1996. p 23.

hrrp:llsile.ebrary.comlliblbrooklyrr!Doc?id=10151042&ppg=38

•

24

kffrey Jerome Cohen

town.edu!lah)·rinthie-cc!nter/int<!r~(fip(aimm.htmJ

(the piece is aho Jorthcomi!l;:\

a nonhrpertext version in Artlruri<llltl. as "The Armour of an Alien;lting Identit;,"i.

33. The Grc:ek \\'ard barbaros, from which we derive the modern E!ljl.1jsh \\ord

barbaric, me-am "malOng the ~ound bar bar~ -that is. not speaking (Jr~ck, a.nd therefore speaking nonSl·rb~.

34. Michel Foucauh. The HI:,1or)'of t:x ualily, vol. 1, Anlnrrod/lrrion, trans, Rob(,rt

Hurley c,r-';cw York: Vintage, 1990). 47-48.

35. Ste..... art, UII LllIIgi,tg. Sec e peciaJ ly ~Thc Imaginary Bod)":' i04-}1.

36. The situa:ion was ob\<lousl ' (ar more complex than thew statements can begin

to show; "E.uropean:· for exampll', usually includ~ s onll' male, of rhe \ estern Latin

tradition. Sexual oricntatjon further complicates the picture, a.,... we )nalJ see.

Donna Hara\"3Y. following Trinh Minh-ha, calls the humans beneath the monstrous skin "inappropriate/d others":' To be 'inappropriate/d' does not me.!n 'not to

be in rdation wilh' I.e., to b<i 10 a ~pecl31 reservallun. With the ~'Alus 01 the iluth.:nlie, the untouChed, In the atIocfiroOlc and allotropic condition oi innocence. Rathe;

to be an 'inappropriat.:fd other' means to be in critical decons.truuive relation3Iir~',

In a dlHT3cung rathc.>r than ref1~cting (ratio)nalirv-~e lliean $...makin

\

tent connection that exceeds dominali . uThe Promi~es 0 :\lonster;,:' in .'II . ns,

Cy/1urgs, ami Women: The ReinvC1Irion of Nr((jlill7lrrt-Nt:~J9I:.k;...B.a.ull.ed,ge,.~~;-%9"i

37. This discussion owes an obvious debt to Mary Douglas, P:mty and Danger: An

An,jh's;$ of rile COn[Cp'S of PoUwion and Taboo ( lew York: Routledge: & Kegan Paul ,

1966 ).

38. John Eastman, Retakes: H.~lJiTld tile SCi'll S oisoo Ci.HSi( .\f<lvies, 9-10 .

39. Paul COd res inter~stingl>' observes that "the horror film bccomes the c- ential

form of cinema. monstrous content manifest.ing itsdf in the monstrous form of the

gigantic slreen." The G(lrgclll~' Gaze (Cambridge: Cambridge Uni\'crsiry Press, 199 1),

77. Carol Clovc.>r loutes some of the pleasure of the man ter film in its cross-gcnda

game of identification; sec .\</err Women. a/ld Clrain Saws: Ge.nder in the Modtrn

Horror Film (PrincelOll, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992)- Why not go further,

and call the pleasure cro~s-somaric~

10. Jacqui:'_ Le Goff, "The Medieval ,,"cst and the Tndian Ocean," in Tim e, "'(lrk

and Culture i1l the Middle Ages, tra ns. Arthur Goldhammer (C hicago: Univer it)' of

Chicago Pr . 1980), 197. The postmodem equivalent of such spaces is Gibsonian

c)'ber pa c~, with i t~ MOO a nd M SHes and other arcnas of unlimited JXJ ibilit '.

4 !. For Mikhail Bakhtin, famou Ir. thi i thl" tran~(ormatiH power of laughter:

"Laughter liberates not only fr-om ex ternal cen~(lf.lhip but fir t (1f all fr m the grc.>3t

internal censor; it liberat' from the ~ ar Ihat developc:d in rr:an during tho IS3 nds of

'ears: fear of the sacred, fear of the pr hibition>,. of the pa~t, (If pC\w.::r." Rabdais (!rid

His WorM, leans. H c!l~ n e lswQI£k (Indianapo lis: Indjanl1 niversiry Pre ', 1984 ) 94 ·

Bakhtin tra e the moment ( a pc to the point at which laughter bl! .Im ' p.lrt of

the "higher level ofliterature, \\Ihcn Rabelais wro! GargonlllJl,;1 PtllIIllg"IeL

42. Th ~ QII I for lire HoI), rail, tr . Pauline Mata ra 0 (London: Pcn u in Books,

j

19 69 ), 194 .

43. Julia Kri<teva, The Powers of Horror: An fun on b,.,ctiotl . trans. Leon S.

Roudkz ( New York.: Columbia Uni,..::r. i Pr ,1 9Rl ), 1.

44 . Judith BUller. BcuJ; n ,at MalTer: 011 til,,' Discursiv(' Limits 0

{New York:

M

Cohen, Jeffrey J.(Editor}. Monster Theory : Reading Cu/rure.

Minneapo/is, MN. USA: University of Minnesota Press. /996. P 24.

hltp:llsile.ebrary.comlliblbrookiynlDoc?id=10151042&PP1F39

.,

•

:-'Ionster CuJ,tur~ (Seven Theses)

25

Routledgr, 1993) u. Bmb ~utJ(r .Ind J have in mind hen: I'Ollcaull'~ nolion of an

emancipation of though t "from what it ilently thin ' 8 tholl will allow "il In think

ditfaently: rlichd Foucault. The

of Pleasure, trans. Roher! Hurley (N(w York:

Vint3se. 1985).9. Michael Uebel amplifie and applies th.· practice to the mon$ter in

hi .. l' say in I.h ~ fu me.

Cohen. Jeffrey J.(Editor). Monster Theory : Reading Culture.

Minneapolis. MN. USA : University a/Minnesota Press. 1996. p 25.

http://site.ebrary.com!liblbrooklyn/Doc?id=10151042&ppg=40