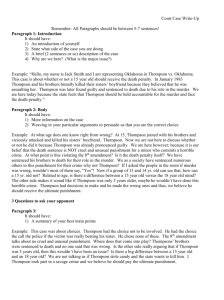

Bright Line Has Been Drawn for Juvenile Executions: Thompson v

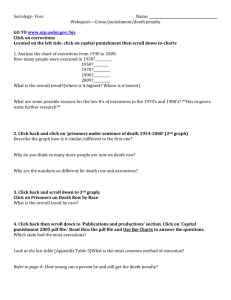

advertisement