Université Paris 10 David V. Snyder Nanterre La Défense American

advertisement

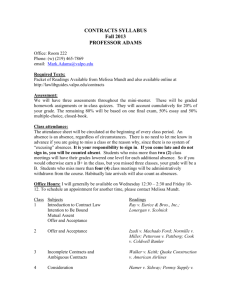

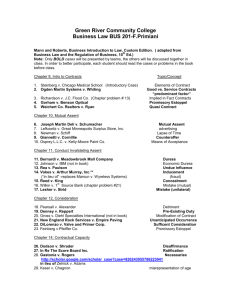

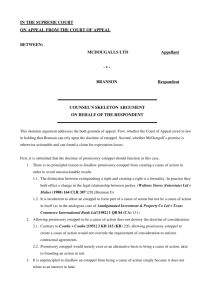

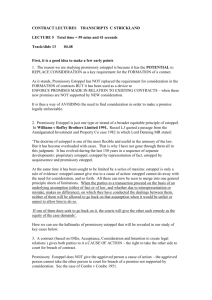

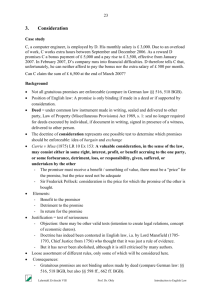

Université Paris 10 Nanterre La Défense Comparative Private Law David V. Snyder American University Washington College of Law COMPARATIVE NOTES ON AMERICAN CONTRACT LAW WITH REFERENCE TO FRENCH LAW David V. Snyder Copyright © 2011 1. The Doctrine of Consideration 1.1. No system of law has been so extravagant as to enforce every promise or every agreement. Something is required beyond the agreement or the promise. In the common law, that additional requirement is consideration, as in French law, traditionally that additional requirement has been cause. 1.2. Definition: consideration is D³EDUJDLQHG-IRUH[FKDQJH´PHDQLQJWKDWHDFKSDUW\ PXVWEHVHHNLQJWRLQGXFHWKHRWKHUSDUW\¶VSURPLVHRUSHUIRUPDQFHDWOHDVWVRIDUDV it would appear to a reasonable person. 1.2.1. In the terms of the first great capitalist, each party must be saying, in HIIHFW³*LYHPHWKDWZKLFK,ZDQWDQG\RXVKDOOKDYHWKLVZKLFK\RXZDQW´ ADAM SMITH, THE WEALTH OF NATIONS 22 (5th ed. London 1789). 1.2.2. ,QRWKHUZRUGVWKHUHPXVWEH³PXWXDOLQGXFHPHQW´ 1.2.3. Corresponds to the French synallagmatic contract. Note that French law recognizes many other kinds of contracts, e.g., the contrat de bienfaisance. The same is not true of American law. 1.3. History: consideration doctrine developed from an older idea that consideration must be either a benefit to the promisor or a detriment to the promise 1.3.1. Benefit to the promisor is based on a property notion. P gave something to D (i.e., gave a benefit to D). D should either give it back (i.e., make restitution) or pay for it. So benefit to the promisor is a restitutionary or property-based idea. 1.3.2. Detriment to the promisee is based on a tort notion. D made a promise, P relied to his detriment, so D should pay for the injury he caused P. So detriment to the promisee is based on the idea of reliance or injury or tort. 1.4. Generally speaking, consideration is required for a contract under American law. (The chief exception, promissory estoppel, is discussed below.) DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 1.5. Applications: Because of the requirement of consideration ± 1.5.1. a promise to make a gift is not generally enforceable. Thus we have cases where the courts have to decide whether a promisor was trying to induce the promisee to do something for real, or was instead merely imposing a condition on a gift. If the latter, then the promise to make the gift is not enforceable. The only way to make a gift reliably under the common law is to make it (as with manual delivery under French law). Promising to make the gift is not good enough. 1.5.2. a modification to an existing contract is another contract (whereby the parties discharge each other from their existing duties under the old contract and take on the new duties of the second contract). That means the modification, because it is a contract, must itself have consideration. Therefore, the modification cannot be one-sided. 1.5.2.1. Thus, where fishermen contracted to fish for the season for $50, and during the season they demanded $75 and the shipowner agreed, the new agreement is not valid. The fishermen did not do or promise anything to induce the promise of the extra $25, so there is no consideration and therefore no valid modification. (Based on Alaska Packers v. Domenico.)1 1.5.2.2. This prevents the fishermen, or others, from coercing a modification to a contract at a time when they have great leverage over the RZQHUVZKRFDQ¶WJHWUHSODFHPHQWILVKHUPHQDWWKDWSRLQW 1.6. Problems with consideration doctrine 1.6.1. Refusing enforcement to perfectly good faith modifications just because there is no consideration can be a problem. Many would like to see this aspect of the consideration doctrine abolished. Courts have recognized exceptions when there are unforeseen circumstances, as in Brian Construction v. Brighenti (where a subcontractor promised to clean up waste in the modification, and not just dig through dirt as in the original contract, the modification for added compensation was valid). The Uniform Commercial Code has outright abolished the consideration rule for modifications to contracts for sales of goods. UCC § 2-209(1). 1.6.2. Gratuitous options (gratuitous options are essentially irrevocable offers where the offeree did not pay for the promise not to revoke for a period of time) are not generally enforceable. Remember: I was free to revoke my promise to \RXWKDW,¶GNHHSRSHQP\RIIer to sell you my business for $10 million. Why? Because you had not given me any consideration (e.g., money) for my promise to leave my offer open for a time. 1 I have provided some case names, but please keep in mind that our discussion of them has been quick and conceptual, and accordingly I have sometimes simplified their facts or holdings. 2 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 1.6.2.1. This problem led the UCC to make a limited exception to the rule when sales of goods are involved, see UCC § 2-205. Note that the rule is not abolished; only a limited exception is provided. 1.6.2.2. Sometimes courts will enforce a fair option even without consideration if the parties make a pretense of consideration (with a recital of consideration, or with nominal consideration²which ordinarily will not work because they are not bargained for, but which can work as an exceptional matter, in the interest of equity and justice, with options) 1.6.3. Settlements of clearly invalid claims are the subject of a split in authority. Some will uphold them if the claimant had a good faith belief in his claim, but some will not²even if the agreement is written in blood, as in Kim v. Son. 1.6.4. Contracts of suretyship are often gratuitous and have thus caused doctrinal difficulties. 1.6.5. As mentioned, the common law has no reliable way to promise to make a gift. 1.7. Compare the French doctrine of cause. 1.7.1. Cause does not result in any such problems. One can have a donative cause. Thus, even a promise to make a gift is supported by cause, as in a contrat de bienfaisance. Similarly, modifications, irrevocable offers, etc. are all supported by cause. Those contracts are thus valid, although a certain kind of cause (e.g., a donative cause) will result in a classification of the contract in such a way that a particular form is required (an authentic act executed before a notary). 1.7.2. Cause and consideration, it may thus be observed, work differently. There is always a cause. The purpose of finding the cause²assuming there is any purpose at all to doing so²is classification. On the other hand, there is not always consideration. If there is not, there can be no contract, generally speaking. 1.7.3. So cause does not result in practical problems as common law does. 1.7.3.1. Sometimes lawyers trained in civil law can scarcely believe that the common law can survive with the doctrine of consideration. Common law scholars often do not try to justify the doctrine but instead observe that the doctrine simply arose as a matter of the historical development of contract law. It is a living artifact of history. 1.7.3.2. The idea of requiring a bargained-for exchange for an enforceable contract might be linked to the association of the common law with markets, exchanges, and commercial transactions. Cause might be linked 3 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT more to the moral act (and moral import) of promising. These are typical explanations. 1.7.3.3. Because cause is so flexible, however, it may be questioned whether the doctrine of cause does anything useful²especially because a contract requires an objet anyway. For some writers, then, cause is theoretically insupportable. 2. Promissory estoppel 2.1. Historical introduction 2.1.1. As we have now seen, consideration came to be required for an agreement or promise to be enforced at common law. 2.1.2. There used to be another basis too: the formality of the seal. This formality was lost, however. A seal no longer makes an agreement enforceable, generally speaking. 2.1.3. This meant that the common law had no way of enforcing various socially useful promises and agreements (see above for list of consideration problems). The loss of the seal created a gap. 2.1.4. The old doctrine of equitable estoppel (also known as estoppel in pais) was adapted to fill the gap. 2.1.4.1. If a party said something outside of court (anything not in court was referred to as ³LQWKHFRXQWU\´RUin pais), and the other party relied on it, then the first party could not say something different in court, even if it ZDVWUXH7KLVZDVDPDWWHURIVLPSOHHTXLW\RUIDLUQHVV³µ,WLVFDOOHGDQ HVWRSSHO¶VDLWKP\/RUG&RNH&R/LWWµEHFDXVHDPDQ¶VRZQDFWRU acceptance estoppeth or closeth XSKLVPRXWKWRDOOHJHRUSOHDGWKHWUXWK¶´2 2.1.4.2. Equitable estoppel required a misrepresentation of fact. A promise would not suffice. The law thus distinguished between a statement of fact OLNH³)Lve hundred dollars were deposited into your account last week,´ DQGDSURPLVHOLNH³,ZLOOSXWILYHKXQGUHGGROODUVLQ\RXUDFFRXQWQH[W ZHHN´7KHODWWHULVDSURPLVHDQGWREHHQIRUFHDEOHJHQHUDOO\KDGWREH supported by consideration. 2.1.4.3. With the loss of the seal, however, courts came more and more to apply equitable estoppel (or other doctrines) to promises to make gifts or donations. Professor Samuel Williston of Harvard noticed this and called it ³SURPLVVRU\HVWRSSHO´WRGLVWLQJXLVKLWIURPHTXLWDEOHestoppel. 2 Lyn v. Wyn, 124 Eng. Rep. 507 (1665). 4 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 2.1.5. As the story is told by Professor Grant Gilmore of Yale, Professor Arthur Corbin (also of Yale) wanted to put a doctrine like cause into the first Restatement of the Law of Contracts. Professor Williston, the person in charge and the older scholar, refused. But he had to admit that Professor Corbin had found a number of cases that could not be explained by a consideration doctrine that required a bargained-for exchange. So he put promissory estoppel into the Restatement as § 90. (This all happened in the early 20th century.) Section 90 has been extremely successful. 2.2. Current doctrine, per RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS § 90(1) (1981)³$ promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of WKHSURPLVH7KHUHPHG\JUDQWHGIRUEUHDFKPD\EHOLPLWHGDVMXVWLFHUHTXLUHV´ 2.2.1. Notice the exceptional quality of the wording: it sounds like promissory estoppel is to be used sparingly, RQO\DVDODVWUHVRUW³LILQMXVWLFHFDQEHDYRLGHG RQO\E\HQIRUFHPHQW7KHUHPHG\PD\EHOLPLWHG´ 2.2.2. Current scholarship studying large numbers of cases suggests that the courts reserve promissory estoppel for exceptional use: it appears, to oversimplify a bit, that a plaintiff is ten times more likely to succeed with an ordinary contract claim than a claim for promissory estoppel. 2.2.3. Courts can be quite stringent RQZKDWWRFRXQWDVD³SURPLVH´LHDWUXH commitment, or what to count as reasonable reliance (was it really reasonable to rely without a contract? would the promisee have taken the action anyway?) 2.2.4. In addition, the courts now often limit the remedy to reliance damages (putting the promisee where it would be had there been no promise, which typically means reimbursing the expenses the promisee has incurred, instead of expectancy damages, which put the promisee where it would be had the promise been performed, which typically means giving the promisee the benefit of its bargain). See below for further discussion of damages and other remedies. 2.3. Courts tend to use promissory estoppel for particular jobs. The number and range of these jobs has grown over the years but seems fairly stable now. 2.3.1. First, gift promises (like a grandfather¶VSURPLVHWRJLYHPRQH\ to a JUDQGGDXJKWHURUDQHPSOR\HU¶VSURPLVHRIDSHQVLRQWo an employee who need not do anything further to earn it). See, e.g., Ricketts v. Scothorn; Feinberg v. Pfeiffer. 2.3.2. Later, the doctrine was extended to subcontractor bids, see Drennan v. Star Paving, even though earlier the courts (in Baird v. Gimbel Bros.) had refused to do so because these are commercial contracts, not gratuitous promises 5 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 2.3.3. Still later, promissory estoppel came to be used in cases of precontractual liability. The most famous cases involve negotiations over the grant of a franchise (like WKHULJKWWRRZQDORFDO0F'RQDOG¶VIDVWIRRGUHVWDXUDQWThe leading cases are Goodman v. Dicker and Hoffman v. Red Owl Stores. 2.3.3.1. Courts are perhaps more stringent now (see above as to difficulty in finding a promise or reasonable reliance), but promissory estoppel can still be used in this context. 2.3.3.2. The subject of precontractual liability at common law is complex. 2.3.3.2.1. Promissory estoppel is only one possible basis for precontractual liability. The courts may also find something entirely different: 2.3.3.2.2. The parties may have completely bound themselves even by an informal agreement, if the parties so intended. This is true even though the parties may have contemplated a longer, more formal contract document to be executed later. E.g., Texaco v. Pennzoil. 2.3.3.2.3. On the other end of the spectrum, the parties may have intended no liability to each other at all. Ball-Co Mfg. v. Empro Mfg. 2.3.3.2.4. One party may have granted an option to the other party. (Recall that an option is essentially an offer that is irrevocable for a period of time.) This is unusual, however, and generally requires consideration. The sense of the rule here (to the extent it is sensible at all, which as you gather from the discussion above is debatable) might come through by thinking of it like this: Why would one party bind itself when the other party is not bound at all? It would presumably only do so if it was getting something (consideration) for that commitment. If nothing is being exchanged for the option, however, the courts will be skeptical that any commitment was made not to revoke the offer. 2.3.3.2.5. The parties may have agreed to negotiate in good faith. This would itself be a contract. 2.3.3.2.5.1. Remember, under American law there is generally no duty to negotiate in good faith. (There are a few exceptions, e.g., in labor law.) 2.3.3.2.5.2. Generally speaking, then, the only way parties would be bound to negotiate in good faith is if they contract to do so. If both parties promise to do so, there is agreement and consideration (the exchange of one promise for another), and the parties are bound, by contract, to negotiate in good faith. Teachers Insurance & Annuity Association v. Tribune Co. is the 6 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT leading case. For a court to find this, though, the agreement to negotiate in good faith must of course be proved. 2.3.3.2.5.2.1. In addition, the complaining party must show that the other party did not negotiate in good faith, i.e., breached its contract. This is often hard to prove, but in some instances the party refuses to negotiate at all (usually because it has found another contracting partner), in which case proof is easy. 2.3.3.2.6. Tort may also give rise to precontractual liability, but this is again difficult to prove. Often a party will try to claim that there was an intentional misrepresentation. With sufficient proof, this will work. It can also try a claim of negligent misrepresentation. Note that there is no tort for negligent promising. (Remember, a promise is a commitment as to the future. If the commitment is not kept, the promise is broken but there is no misrepresentation. A misrepresentation must be an untrue statement about existing facts.) 2.3.3.2.7. The parties may arrange precontractual liability by an express preliminary contract (e.g., A and B agree to negotiate on a merger. Either party may terminate negotiations at any time but must pay the other party $1 million.) If a party must pay in order to terminate negotiations, there are some possible restrictions. These restrictions are beyond the current topic, but put very simply, they can arise from contract law (American contract law does not allow penal clauses, and the $1 million might be construed as a penalty if it is not a reasonable estimate of damages) or from corporate law (these clauses are usually between corporations, and corporate law may invalidate such a clause because of concern about WKHFRUSRUDWLRQ¶VVKDUHKROGHUV 2.4. Comparative and theoretical notes on promissory estoppel 2.4.1. It has traditionally been thought that promissory estoppel has no place in civil law. Promissory estoppel is seen as a response and exception to the consideration requirement, and since civil law does not require consideration, it does not need promissory estoppel. 2.4.2. Other promissory estoppel jobs are filled by earlier civil law doctrines, particularly abus de droit in France and culpa in contrahendo in Germany, both of which are based on tort notions. 2.4.2.1. Theorists thus tend to associate promissory estoppel with tort. 2.4.2.2. In addition, as promissory estoppel arises from the injury to the plaintiff, it sounds like a tort: it is founded on the injury done (detrimental 7 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT UHOLDQFHWRWKHSODLQWLIIEHFDXVHRIWKHGHIHQGDQW¶VZURQJEURNHQ promise). 2.4.2.3. This view is refuted by the recent case of Barnes v. Yahoo! (the subject of our T.D.), which emphasizes that promissory estoppel requires a promise, and a promise make the theory contractual. 2.4.2.3.1. Contractual liability is based on consent. When defendant makes a promise, it is manifesting its consent. 2.4.2.3.2. The manifested consent separates contractual liability from the liability that arises from tort or from statute. Tort or statutory liability does not require any form of consent from the defendant. Defendant is held liable regardless of consent. 2.4.2.4. While reliance, and thus injury to the plaintiff, is indeed a tort-like notion, it is not entirely separate from contract. Recall (see discussion above on consideration) that contractual liability grew out of notions of liability in tort (detriment to the promisee, which is similar to detrimental reliance) as well as notions of property (benefit to the promisor). 2.4.3. More recently, the Cour de cassation recognized something like SURPLVVRU\HVWRSSHOZKHQLWJDYHLWVEOHVVLQJWR³O¶estoppel´RU³O¶interdiction GHVHFRQWUHGLUHDXGpWULPHQWG¶DXWUXL´ 2.4.3.1. It appears that the doctrine is gathering sophistication and nuance in very recent cases like Cass. ass. plén., 27 févr. 2009, nº 07-19.841. See generally Philippe le Tourneau, Droit de la Responsabilité et des Contrats § 2206 (8th ed. 2010). To what extent this is merely equitable estoppel and to what extent it is like promissory estoppel is not clear to me. 2.4.3.2. The doctrine appears to be linked to basic ideas of French law, like bonne foi , and to the Romanesque doctrine venire contra factum proprium non valet. 2.4.3.3. You heard me question why French law would need this doctrine, given the points above (flexibility of cause, without a requirement of exchange, with supplementation available through tort doctrines like abus de droit). This question was the source of some discussion, particularly in the T.D., but also in the lecture. I remain curious. 3. The objective theory of assent 3.1. Aside from consideration (or a substitute for consideration, like promissory estoppel), a contract requires an agreement. This is usually known as the requirement of mutual assent. 8 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 3.2. Mutual assent in the common law uses an objective theory, which means that assent is judged from the standpoint of a reasonable person. (We noted the literary and FXOWXUDOGLIIHUHQFHEHWZHHQWKH³UHDVRQDEOHSHUVRQ´DQGWKH³bon père de famille´ DOOXGLQJWR1LFKRODV.DVLUHU¶VUHDGLQJRIODZVIURPDKXPDQLVWLFVWDQGSRLQW 3.2.1. We drew one example from Embry v. Hargadine, McKittrick Dry Goods Co. Where DQHPSOR\HHVD\VVRPHWKLQJOLNH³,¶PTXLWWLQJULJKWKHUHDQGQRZ XQOHVV\RXDJUHHWRHPSOR\PHIRUD\HDU´DQGWKHERVVUHVSRQGV³Go ahead, you're all right; get your men out and don't let that worry you´DFRXUWPD\KROG that a contract of employment for one year has been formed because a reasonable person would XQGHUVWDQGWKHERVV¶VUHVSRQVHWKDWZD\in this context, HYHQWKRXJKWKHERVVGLGQRWKLPVHOI³VXEMHFWLYHO\´PHDQLWWKDWZD\ 3.2.1.1. Even if the boss had written a memorandum to the board of directors after this meeting, saying that he did not intend a contract, that memorandum is probably irrelevant. If the employee took it to be a commitment for a contract for a year, and if a reasonable person would have taken it that way, there is objective assent, and that is all that is necessary. 7KHERVV¶VVXEMHFWLYHZLOOGRHVQRWPDWWHU 3.2.1.2. An aside: in discussing this case, we mentioned the traditional $PHULFDQSUHVXPSWLRQWKDWHPSOR\PHQWLV³DWZLOO´DQGWKDWWKHHPSOR\HU may let go an employee (and the employee may quit) for any reason, whether it be a good reason, or no reason at all, or even a bad reason (subject to exceptions, like racial or gender discrimination) 3.2.2. Another example is Lucy v. Zehmer. Lucy wanted to buy a farm from Zehmer and had been trying to do so for some time. The Saturday before &KULVWPDVKHVKRZHGXSDW=HKPHU¶VUHVWDXUDQWZLWKDERWWOHRIZKLVNH\DQG they drank, but not to the point of intoxication. They signed a purported agreement on the back of a restaurant check. The seller claimed it was a joke. The court held that a reasonable person would have taken it as real, given that the parties had talked about it for some time, had discussed having the title examined, and had revised the back-of-the-check agreement to include the signature of the wife/co-owner. 3.2.3. A further example is the PEERLESS case, Raffles v. Wichelhaus. Buyer and seller made an agreement for cotton to arrive ³ex PEERLESS.´ There turned out to be a number of ships with that name. The parties had not agreed subjectively (one was thinking of the December PEERLESS, and the other was thinking of the October PEERLESS), and a reasonable person would not know which PEERLESS was meant either. There is a failure of assent, and no contract. 3.3. Again, the so-FDOOHG³SUHFRQWUDFWXDO´FRQWH[WFDQSURYLGHDJRRGLOOXVWUDWLRQIRUKRZ these ideas are implemented. 9 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 3.3.1. In a large or complex transaction, the parties often plan eventually to sign a carefully drafted, elaborate, and lengthy contractual document (sometimes FDOOHGD³ZULWWHQPHPRULDO´RIWKHLUDJUHHPHQW Even if they intend such a document, the law allows them to be bound earlier if they want to be. For example, the presidents of the businesses may agree to be bound now, even though their lawyers will draft a document that will be signed in two weeks. Alternatively, if they do not wish to be bound until the lengthy document is signed, the law allows that result as well. It all depends on their agreement. 3.3.2. That agreement must generally be discerned based on what they have said and their other manifestations of assent (such as what they have done), as those statements and actions would be understood by a reasonable person. 3.3.3. In the precontractual context, there will often be signs pointing in both directions, because often both parties are trying to tie up the other without themselves being tied. This situation will lead to contradictory signals, which a court (or a jury) will have to interpret. 3.3.4. So in one of the largest cases in the history of the world (the verdict was more than $10 billion), a court upheld a jury finding that the parties to a merger of oil companies intended to be bound (so far as a reasonable person could tell) E\DIRXUSDJH³0HPRUDQGXPRI$JUHHPHQW´HYHQWKRXJKWKH\LQWHQGHGDPXFK lengthier and more formal documentation to be signed later. Texaco v. Pennzoil. Thus the four-page memo was held binding. 3.3.5. We get a lot of litigation over whether a so-FDOOHG³OHWWHURILQWHQW´RU ³PHPRUDQGXPRIXQGHUVWDQGLQJ´RU³DJUHHPHQWLQSULQFLSOH´RU³JHQWOHPHQ¶V agreemenW´LVELQGLQJ7KH\FDQEHDVLQTexaco v. Pennzoil, but they may not be, as in Empro (above). The court will have to sort the evidence from the standpoint of a reasonable person. 3.4. The reason to use the objective theory is the policy in favor of reliability. The PDUNHWSODFHDQGWKXVWKHODZFDQKDUGO\DOORZPHWRVD\³,ZLOOVHll you my EXVLQHVVIRUPLOOLRQ´DQGWKHQDOORZPHODWHUWRVD\³,NQRZ,VDLGWKDWEXW, was actually thinking at the time that I would not sell my business at all, so you cannot hold me to what I said before. It does not, and did not, reflect my true, VXEMHFWLYHZLOO´5DWKHUWKHODZDOORZV\RXWRVD\³,DQGDUHDVRQDEOHSHUVRQ ZRXOGEHMXVWLILHGLQWKLQNLQJ\RXZRXOGVHOO\RXUEXVLQHVVIRUPLOOLRQ7KDW¶V whaW\RXVDLGZKDW\RXUWUXHZLOOZDVGRHVQ¶WUHDOO\PDWWHU´ 3.4.1. Understanding the policy justification is crucial because the policy generates not only the general rule but also the exceptions. Therefore: 3.4.1.1. We usually use the objective theory of assent. We also think that objective assent and subjective assent are the same²one would hope that people usually do not misstate what they are thinking. 10 DAVID V. SNYDER 3.4.1.2. COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT However: 3.4.1.2.1. If A knows or has reason to know what B is thinking, we will use %¶VVXEMHFWLYHDVVHQW$IWHUDOO$NQRZV it or should know it, and we GRQ¶WQHHGWRUHVRUWWRWKHUHDVRQDEOHSHUVRQWHVW 3.4.1.2.2. Also, if A and B subjectively agree, we use their subjective agreement, regardless of what a reasonable person would think. A DQG%¶VDJUHHPHQW is the ideal case of contract: true meeting of the minds, as opposed to the presumed meeting of the minds based on the SDUWLHV¶PDQLIHVWDWLRQVRIDVVHQW as understood by a reasonable person. 3.5. French law recognizes the same policy but seems to come from the other direction. 3.5.1. American law is usually understood to be something like: use the objective theory, unless the subjective theory makes sense. French law is usually understood to be something like, Contract is based on the will of the parties. We use their actual will, except when the objective theory makes sense. 3.5.2. It seems that both systems probably arrive at the same results most of the time, although they start on opposite ends. 3.5.3. The starting points may (again) reflect different attitudes and orientations. This is the traditional understanding, with the civil law taking a more moral or philosophical view, based on will theory, and the common law taking a more commercial or mercantile view, using the objective theory. 4. Remedies 4.1. The general remedy for breach of contract in American law is monetary FRPSHQVDWLRQ³GDPDJHV´7UDGLWLRQDOO\WKHRULVWVKDYHUHFRJQL]HGWKUHHGDPDJHV interests: 4.1.1. Expectancy damages seek to put the plaintiff (assumed to be the promisee) where it would be had the contract been perfor med. This gives the plaintiff the benefit of its bargain. 4.1.2. Reliance damages seek to put the plaintiff where it would be had there been no contract. This usually is reimbursement of the expenses plaintiff has incurred in reliance on the contract and is usually less generous than expectancy. 4.1.3. Restitution damages seek to put the defendant (here assumed to be the promisor) where it would be had there been no contract. It typically makes the defendant (the party in breach) disgorge any benefit it received under the contract. It is usually the least generous measure of damages. 11 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 4.2. Recall our example. I offer to sell you my business for $10 million, and you accept, all on the assumption that you will have a chance to check the business first. The business is worth $15 million. You have spent $300,000 on due diligence (e.g., for auditors and lawyers to check to make sure you are getting what you bargained for) when I breach, but you have not yet paid me anything. 4.2.1. Expectancy damages are $5 million. Had the contract been performed, you would have received a $15 million business in return for the $10 million price. That $5 million is the benefit of your bargain. 4.2.2. Reliance damages are $300,000. If you get $300,000, you are where you were before the contract. This restores your status quo before the contract. 4.2.3. Restitution damages are zero, as I have received zero. If I had received some benefit (e.g., if you had paid me a deposit), I would have to return it (i.e., ³PDNHUHVWLWXWLRQ´ 4.3. The usual measure of damages in contracts cases is expectancy damages. 4.3.1. The policy is again reliability. 4.3.2. Suppose you own a boulangerie and you and I make a contract so that I will sell you high-JOXWHQIORXUIRU¼40 for 100 kg to be delivered June 1. On June 1, I fail to deliver, and at that time you have to pay ¼IRUNJRIVXFK IORXU<RXKDYHQRW\HWSDLGPHOXFN\IRU\RX<RXUGDPDJHVDUH¼<RX ZHUHDOZD\VJRLQJWRKDYHSD\¼WRPH<RXVWLOOKDYHWRSD\WKDWSOXV DQRWKHU¼7KHODZPDNHVPHJLYH\RXWKHH[WUD¼2QFHHYHU\WKLQJLV done, you will have the 100 kg of flour you bargained for. You will have paid ¼IRULWEXW¼RIWKDWFDPHIURPPHVR\RXHIIHFWLYHO\SD\¼WKHVDPH you would have paid me. 4.3.2.1. This means you can rely on your contract with me. 4.3.2.2. Even if I breach, the law puts you where you would be had I performed. 4.3.2.3. So you can plan your business, set your prices, set your wages, and so on, all knowing that you can count on your contract with me, whether I perform or not. 4.3.3. We use reliance damages in exceptional cases, as where expectancy cannot be proved with reasonable certainty, or in many current promissory estoppel cases. 4.3.4. We usually use restitution damages where there is no valid contract. 12 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 4.4. Note the absence, so far, of discussion of a performance remedy. The common law onO\DOORZVDSHUIRUPDQFHUHPHG\FDOOHG³VSHFLILFSHUIRUPDQFH´LIGDPDJHV provide an inadequate remedy. 4.4.1. 7KLVUXOHLVWKHUHVXOWRIKLVWRU\7KH³FRXUWVRIODZ´FRXOGQRWJLYHDQ order that a person do something or refrain from doing something. The chanceOORUZKRKDGD³FRXUWRIHTXLW\´FRXOGJLYHVXFKDQRUGHUDQGKDGWKH power to enforce his order²even by imprisonment²but the chancellor was busy helping to run the kingdom and would only interfere if the plaintiff could show that he had no adequate remHG\³DWODZ´2QO\WKHQFRXOGSODLQWLII SURFHHG³LQHTXLW\´$OWKRXJKQRZLQPRVWMXULVGLFWLRQVWKHVDPHFRXUWVFDQ hear both legal and equitable matters, an equitable claim still requires the equitable showings, which are typically: 4.4.1.1. no adequate remedy at law 4.4.1.2. irreparable harm in the absence of equitable relief 4.4.1.3. JRRGPRUDOVWDQGLQJXVXDOO\FDOOHGDUFKDLFDOO\³FOHDQKDQGV´ 4.4.1.4. consistency with the public interest 4.4.1.5. not overly burdensome for the court 4.4.2. These rules are still very much enforced. For instance, in Texaco v. Pennzoil, one party sought an order to effectuate the original, contracted-for merger and to forestall a rival merger. The court refused, holding that if the plaintiff proved its case, it could be compensated with damages (as it eventually was). It therefore had an adequate remedy at law, and an order for specific performance was denied. 4.4.3. On the other hand, if the plaintiff can make the equitable showings, it may be awarded specific performance. This is typically the case for 4.4.3.1. real estate 4.4.3.2. goods that are unique (e.g., a work of art) or functionally unique (goods that are so rare in relation to demand that obtaining substitute goods is not a commercially reasonable possibility). UCC § 2-716. 4.4.4. Specific performance is not available in the usual way for personal services. For example, a court will not order a boxer to fight. If his services are unique or functionally unique, however, a court may order him not to fight for anyone other than the plaintiff. 4.4.4.1. 7KLVLVFDOOHGD³QHJDWLYHLQMXQFWLRQ´ 13 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 4.4.4.2. It does not require the defendant to do anything, and thus does not violate his liberty interest. In addition, the court need not undertake to evaluate whether his performance is adequate, which could be very difficult in personal services contracts (could a judge tell whether the boxer was fighting as hard as he could?). So the reasoning goes; it is subject to some GHEDWHDIWHUDOOGRHVQ¶Wthe negative injunction seek to force the defendant to do something, thus raising the same liberty and verifiability concerns? 4.5. At least theoretically, French law is the opposite: performance (O¶H[pFXWLRQHQ nature) is an ordinary remedy under well-established doctrine, despite Code civil article 1142, which seems to prohibit exécution en nature of faire obligations.3 4.5.1. The prohibition on specific performance for faire or ne pas faire obligations is understood to apply only to personal services (which would, of course, include boxing!) 4.5.2. For many decades, it was unclear how serious French law was about enforcing an order for exécution en nature. The astreinte (a monetary penalty) was available in cases of violation of the order, but it was subject to question. Now, however, the astreinte has been regularized and may exceed any potential damages, making it an effective means of enforcement. This has been true since at least the 1970s, based on the view of the Cour de cassation, 20.10.1959, S.1959.225, D.1959.537, and the loi of 5 July 1972, No. 72-626. 4.5.3. The systemic differences in attitudes to remedies is typically taken, again, to indicate different orientations, with the civil law taking a more moral view and the common law taking a more commercial approach. 4.5.3.1. In common law systems, a contract is sometimes viewed (especially by certain scholars and economists) as an option either to SHUIRUPRUWRSD\DIHHWKH³IHH´EHLQJGDPDJHV 4.5.3.1.1. This is particularly true in cases of so-FDOOHG³HIILFLHQWEUHDFK.´ Some people think a party should be encouraged to breach if it would be an efficient breach. Consider Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge 3 As I understand it, the reasoning goes something like this: Exécution en nature is generally allowed, except in faire obligations (article 1142). Nevertheless, even in faire obligations anything done in contravention of the obligation may be destroyed (article 1143), and anything not done may be obtained by WKHSODLQWLIIDWWKHGHIHQGDQW¶VH[SHQVHDUWLFOH7KHGHIHQGDQWPD\HYHQEHUHTXLUHGWRSD\DKHDGRI time. Act n° 91-650 of 9 July 1991, art. 82 Journal Officiel du 14 juillet 1991 (effective Aug. 1, 1992). The plaintiff may obtain such relief even if he has suffered no damage, as the Code does not require any showing of damage. This means that properly understood, articles 1143 and 1144 actually do provide for exécution en nature of faire obligations, and the only point of article 1142 is to prevent an order for execution of a personal services obligation. The Cour de cassation has so held. Civ. 20.1.1953, D. 1953.222, JCP 1953.II.7677. My understanding is based in SDUWRQ%DUU\1LFKRODV¶VH[SRVLWLRQLQTHE FRENCH LAW OF CONTRACT 218-19 (1992). 14 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT Company.4 A county contracts with a company for a bridge to be built because a new factory is contemplated. The plans for the factory are cancelled, however, and the county tells the company to stop work. The common law holds that the company should stop work, should receive reimbursement for money expended or committed so far (minus any salvage value), and should also receive the profit it would have made had the bridge been completed. If the company does not stop but instead builds the whole bridge and sues for the whole price, it cannot recover the full amount. Why? 4.5.3.1.1.1. The company is just as well off if it receives its outlay at the time of breach plus its anticipated profit. It would be no richer by building the rest of the bridge and recovering the whole price. 4.5.3.1.1.2. The county is better off without having to pay for a whole bridge that will be useless. (In the real case, the bridge was in fact built, and it is still there today, in the middle of a forest. It cannot be used, except for an occasional picnic!) 4.5.3.1.1.3. Since the company is no worse off by stopping work and receiving compensation, and the county is better off, society is better off. (This will always be true: if no one is worse off, and someone is better off, the wealth of society has grown. This is a ³3DUHWRVXSHULRU´HFRQRPLFRXWFRPH 4.5.3.1.1.4. The county did breach, and it should. That is the better, PRUH³HIILFLHQW´RXWFRPH7KHFRXQW\PXVWSD\GDPDJHV for its breach²note that this doctrine does not forgive the breach!²but full performance should not be encouraged; it would be wasteful. $VWKLVLVDQ³HIILFLHQWEUHDFK´WKHODZVKRXOGHQFRXUDJHLWE\ awarding the appropriate measure of damages and should not require performance. 4.5.3.1.1.5. Some, then, see the common law emphasis on damages as an economically efficient, practical, market-oriented approach. (You should note, though, that this is subject to question; indeed, economists and others have raised serious questions about whether the theories explained above really hold true.) 4.5.3.1.2. In sum, the idea of damages is that they encourage the most economically efficient outcome. 4.5.3.2. The civil law, however, is committed more to the moral importance of keeping a promise. 4 This discussion reflects American law; English law may be different on this point. 15 DAVID V. SNYDER COMPARATIVE NOTES ON THE LAW OF CONTRACT 4.5.3.2.1. Damages compensate for a broken promise, but the promise is still broken. Performance means that the promise is not broken²faith is not breached (there is no fidei laesio, to use ecclesiastical terms). 4.5.3.2.2. Arguably this orientation is reflected in other default and damages doctrines, like mise en demeure and the requirement of judicial involvement for the dissolution of a contract. Neither of these has a counterpart in the common law. 4.5.4. It is easy to make too much of this difference, and one might ask whether remedies wind up like assent: the systems start on opposite ends but both wind up in the middle, more or less in the same place, in practical terms. 4.5.4.1. Even in the civil law, a plaintiff often (perhaps generally) will prefer a remedy of monetary compensation. After all, the defendant already has failed to perform, and the plaintiff would probably prefer not to be in WKHGHIHQGDQW¶VXQWUXVWZRUWK\KDQGV6RPHUHVHDUch shows that this is the case: parties in civil law countries do not generally seek performance (although the most convincing research does not come from France). As a practical matter, then, the commitment to performance as a remedy is more theoretical than real, even in the civil law. 4.5.4.2. Even in the common law, specific performance is available in the cases when a plaintiff is most likely to want it. 4.5.4.3. In the end, plaintiffs in both systems will usually ask for and receive damages, but will receive performance in the cases when they are most likely to want it. 4.5.5. Nevertheless, the rules and doctrine do seem to reflect real differences, even if they are to some extent differences in theory. One might see this GLIIHUHQFHDVD³KHDGVKDNLQJPRPHQW´DV,SXWLW-RKQ+RQQROGDQ$PHULFDQ scholar, discussed the difference between the civil and common law systems with respect to performance and damages as an occasion where lawyers might well look at each other and shake their heads. An American lawyer might shake his head and wonder: How can the civil law be committed to an idea that is so impractical? A French lawyer might shake his head and respond: How can the common law be committed to a system that is so immoral? 16