Seattle's Sisters of Providence

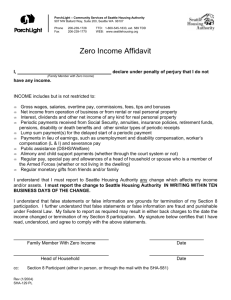

advertisement