The Future of Urban Sociology

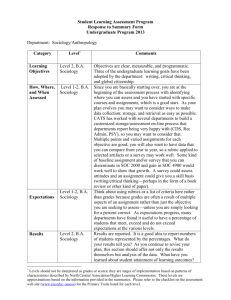

advertisement