Book Review - 'Zeitoun,' by Dave Eggers - Review

advertisement

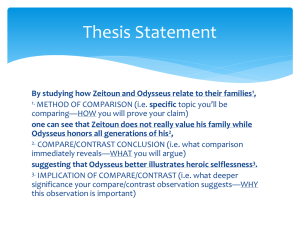

Book Review - 'Zeitoun,' by Dave Eggers - Review - NYTimes.com 1 of 3 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/16/books/review/Egan-t.html?_r=1&p... August 16, 2009 By TIMOTHY EGAN Imagine Charles Dickens, his sentimentality in check but his journalistic eyes wide open, roaming New Orleans after it was buried by Hurricane Katrina. He would find anger and pathos. A dark fable, perhaps. His villains would be evil and incompetent, even without HeckuvaJob-Brownie. In the end, though, he would not be able to ZEITOUN By Dave Eggers Illustrated. 351 pp. McSweeney’s Books. $24 constrain himself; his outrage might overwhelm the tale. In “Zeitoun,” what Dave Eggers has found in the Katrina mud is the full-fleshed story of a single family, and in telling that story he hits larger targets with more punch than those who have already attacked the thematic and historic giants of this disaster. It’s the stuff of great narrative nonfiction. Eggers, the boy wonder of good intentions, has given us 21st-century Dickensian storytelling — which is to say, a character-driven potboiler with a point. But here’s the real trick: He does it without any writerly triple-lutzes or winks of postmodern irony. There are no rants against President Bush, no cheap shots at the authorities who let this city drown. He does it the old-fashioned way: with show-not-tell prose, in the most restrained of voices. In that sense, “Zeitoun” has less in common with Eggers’s breakthrough memoir, “A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius” (which met with mostly deserved trumpet-blaring in 2000), than it does with his 2006 novel “What Is the What,” the so-called fictionalized memoir of a real-life refugee of the Sudanese civil war. In that book, Eggers’s voice took a back seat to his protagonist’s outsize story. But it was an odd hybrid. “Zeitoun” is named for the family at the center of the storm. Abdulrahman Zeitoun is a middle-aged SyrianAmerican father of four, owner of a successful painting and contracting firm. He works hard and takes good care of his loved ones, in America and in Syria. He is also the kind of neighbor you wish you could find at Home Depot. His wife, Kathy, has Southern Baptist big-family roots, but drifts after a failed early marriage until she finds a home in Islam and a doting husband in Abdul. Her hijab is a problem for her family, and for many citizens in post-9/11 America. Yet her charms and his smarts make for a good pairing at home and at the office — which is often the same place, an old house in the Uptown neighborhood of New Orleans. Eggers starts things out at a slow simmer, two days before the storm arrives, with tension in the air, people fleeing, anxiety as heavy as the humidity. It’s Hitchcock before the birds attack. Once he starts to turn up the gas, he never lets up. Kathy flees with the children, first to a crowded, anxious house of relatives in Baton Rouge and then west to Phoenix. She begs Zeitoun to join them. But he’s been through storms before, he says, and besides, somebody needs to stay behind and watch the fort. 7/31/2012 11:32 AM Book Review - 'Zeitoun,' by Dave Eggers - Review - NYTimes.com 2 of 3 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/16/books/review/Egan-t.html?_r=1&p... Katrina hits in the early hours of Monday, Aug. 29, 2005, the day after the mandatory evacuation ordered by the mayor. It’s a Category 5 storm before landfall, with winds over 150 miles an hour. Zeitoun expects his house to leak, maybe some windows to shatter, but he’ll be fine. As a precaution, he fetches a 16-foot aluminum canoe that he had purchased secondhand for $75. Day 1, post-storm, no problem: about a foot of storm sludge in the streets. Day 2, the world changes. Zeitoun wakes to a sea of water, after the levees have failed. He’s neck-deep in a city of a thousand acts of desperation. “He knew it would keep coming, would likely rise eight feet or more in his neighborhood, and more elsewhere,” Eggers writes. At that point, Zeitoun reaches into his aquarium, knowing his fish won’t survive there. “He dropped them in the water that filled the house. It was the best chance they had.” Kids: that’s the kind of reporting detail that makes a book like this come alive. Thereafter it’s an odyssey with the quality of an unpleasant dream, at times surreal, in which Zeitoun paddles around New Orleans in his canoe for a week, an angel of mercy. This section, which takes up the middle third of the book, reminded me of Cormac McCarthy’s postapocalyptic fiction, with the added bonus of proper punctuation. Zeitoun saves elderly and dehydrated residents trapped in rotting, collapsing homes: “Help me,” comes the voice of an old woman. “Her patterned dress was spread out on the surface of the water like a great floating flower. Her legs dangled below. She was holding on to a bookshelf.” In his first day in the canoe, Zeitoun assists in the rescue of five residents. “He had never felt such urgency and purpose,” Eggers writes. “He was needed.” At night, Zeitoun sleeps in a tent on the flat part of his roof. By day, he’s out among the killing waters that buried New Orleans, polluted with garbage, oil, debris, the scraps of people’s lives. “It smelled dirtier every day, a wretched mélange of fish and mud and chemicals.” But within a week, the sense of menace and edgy despair becomes overwhelming. Now Zeitoun’s days are like a watery version of Dante’s “Inferno,” with flood and disease and tough moral choices around every bend: rescue or paddle on? The book takes a sudden turn when six armed officers show up at Zeitoun’s house. He thinks they are there to help him, and he’s happy to point them to people in need of assistance. Wrong assumption: Zeitoun is taken away at gunpoint. After that he goes missing, with no contact with the outside world. His wife assumes, after six days without communication, that he’s dead. This is perhaps the most haunting part of the book, and Eggers’s tone is pitch-perfect — suspense blended with just enough information to stoke reader outrage and what is likely to be a typical response: How could this happen in America? Only a spoiler would reveal anything beyond this point. Suffice it to say that Zeitoun is mistaken for a terrorist and subjected to a series of humiliations, locked in a cage, then a prison, all the while without being charged with anything or even being allowed to make a phone call to his wife. The Bush war on terror had come home. FEMA, once a model of government disaster response, is in this 7/31/2012 11:32 AM Book Review - 'Zeitoun,' by Dave Eggers - Review - NYTimes.com 3 of 3 http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/16/books/review/Egan-t.html?_r=1&p... account a band of paramilitary thugs, seeing everything through the dark lens of counterterrorism. Zeitoun was Syrian-American and loose in New Orleans. That’s all the authorities needed to know. In the end, as mentioned, “Zeitoun” is a more powerful indictment of America’s dystopia in the Bush era than any number of well-written polemics. That is in large part because Eggers has gotten so close to his subjects, going back and forth between Syria and America, crosscutting to flesh out the family and their story. “This book does not attempt to be an all-encompassing book about New Orleans or Hurricane Katrina,” Eggers writes in his author’s note. Of course not. But my guess is, 50 years from now, when people want to know what happened to this once-great city during a shameful episode of our history, they will still be talking about a family named Zeitoun. Timothy Egan’s latest book, “The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America,” will be published in October. He writes the Outposts column for NYTimes.com. This article has been revised to reflect the following correction: Correction: September 6, 2009 A review on Aug. 16 about “Zeitoun,” Dave Eggers’s account of the experiences of a New Orleans contractor, Abdulrahman Zeitoun, during and after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, referred imprecisely to some aspects of the storm. While there were strong winds and heavy rain at Zeitoun’s house on the evening of Aug. 28, the hurricane didn’t “hit” on that date; it made landfall in Louisiana in the early hours of Aug. 29. And while Katrina was at one point a Category 5 storm, by the time of landfall, it was Category 3. The review also referred incompletely to the subsequent flooding of New Orleans. While some of it was indeed the direct result of overtopping of the levees, a larger portion was due to their structural failure. Copyright 2009 The New York Times Company Privacy Policy Terms of Service Search Corrections RSS First Look Help Contact Us Work for Us Site Map 7/31/2012 11:32 AM