Australia

advertisement

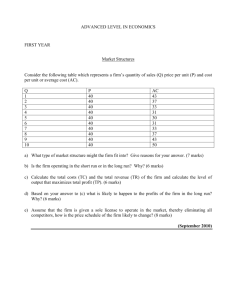

Question Q218 National Group: Australian National Group Title: The requirement of genuine use of trademarks for maintaining protection Contributors: Mary Padbury, Fiona Brittain, Ben Hopper, Liam Nankervis, Joanna Lawrence, Amruta Bapat, Michelle Ta, Grant Fisher Reporter within Working Committee: Mary Padbury I. Analysis of current law and case law The Groups are invited to answer the following questions under their national laws: 1. Is genuine use a requirement for maintaining protection? What is the purpose of requiring genuine use? Is it to keep the register uncluttered and to thereby allow for new proprietors to make use of a “limited” supply of possible marks? Is the purpose of requiring genuine use to protect consumers from confusion as to the source of origin of the goods or services? Or are there multiple purposes? In Australia, the requirement of use is explicit in the statutory definition of a "trade mark": "a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services".1 However, there is no formal requirement that Australian Trade Mark registration owners lodge proof of use or the like on a periodic basis. Nonetheless, an Australian Trade Mark registration is vulnerable to being expunged or partially expunged or being endorsed with limitations as a result of a non-use application. A condition of registration of a trade mark is that it must be used or intended to be used.2 The generally understood purpose of this requirement is to prevent 1 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 17 (Emphasis added). 2 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 27(1). 1 212805252 the Trade Marks Register from becoming cluttered with unused marks, imposing substantial (unwarranted costs) on future traders.3 It should be noted that, where satisfied that it is reasonable to do so,4 the Registrar has a discretion not to remove a mark that has not been used in relation to the specified goods or services. The discretion is only enlivened where the non-use application has been opposed.5 The factors that the Registrar may take into account in exercising his or her discretion include whether the trade mark has been used by the registered owner in respect of similar or closely related goods or services.6 Courts have stated that consideration of the public interest is important to the exercise of this discretion to ensure that consumers are not confused or deceived by the mark being removed from, or remaining on the register,7 and to have aregister that "confines registrations to accord with the realities of use".8 Whilst older authority indicated that exceptional circumstances would be required to justify refusal of a non-use application,9 recent decisions have contradicted this proposition. For example, in one case, the trade mark owner had used the PIONEER & Device mark in relation to audio-visual products and peripheral computer devices, but not at all in relation to other specified computer goods. Nonetheless, the Court exercised the discretion not to remove the mark on the basis that, due to the general practice of brand extension engaged in by providers of multimedia and computer products, consumers would be led to believe that a computer product sold under the name "PIONEER" or the PIONEER & Device mark would be associated with the registered owner.10 2. What constitutes genuine use of a trademark? In summary, for the purposes of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (Act), use must be: (i) in good faith; (ii) as a trade mark; (iii) in the course of trade; (iv) in Australia; 3 L Bently and R Burrell, 'The Requirement of Trade Mark Use' (2002) 13 AIPJ 81, 181-2, 185-8. 4 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-ss 101(3). 5 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 97(1) and sub-s 101(1). 6 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-ss 101(3) and 101(4). 7 Paragon Shoes Pty Ltd v. Paragini Distributors (NSW) Pty Ltd (1988) 13 IPR 323. 8 Upjohn Company v Sanofi (1998) 42 IPR 576. 9 Re J Lyons & Co Ltd's Application [1959] RPC 120, 130 (Lord Evershed). 10 [2009] FCA 135. See also Soncini v Registrar of Trade Marks [2001] FCA 333. 2 212805252 (v) upon or in relation to the goods and/or services;11 and (vi) by the trade mark owner, predecessor in title or an authorised user. Whether a sign is used as a trade mark is to be judged objectively.12 It is not necessary that there be actual trade in the sense of offering for sale or actual sale of goods or services in relation to the mark. However, use must go beyond investigating whether to use the mark. The owner must have reached the stage where it can be seen objectively to have committed itself to using the mark, ie, to carrying its intention to use the mark into effect.13 Sales of goods bearing the mark in Australia without the knowledge of the registered owner constituted genuine and good faith use of the mark even though there had been no conscious projection of the branded goods into the Australian market.14 Use of a sign to indicate quality or describe a good or service offered for sale is generally not considered to be genuine use. Examples include: o use to indicate a particular message about the qualities of a good or service has been found to not constitute genuine use.15 o use of the word "Colorado" on the front of a Colorado themed store was not genuine use of the mark in relation to goods.16 o production and sale of an electric shaver whose faceplate closely resembled two registrations of two-dimensional depictions of a faceplate of an electric shaver was not use as a trade mark.17 3. Is use “as a mark” required for maintaining protection? Is use as a business name, use in advertising or use on the Internet sufficient? Is use of a mark in merchandising genuine use for the original products? (For instance, is use of the movie title Startrek, registered for clothing and used on the front of a TShirt, genuine use of the mark for clothing?) Use "as a mark" is a requirement to defend against actions to remove a mark from the Register. In Australia, use "as a trade mark has been defined as: 11 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-ss 7(4) and 7(5). 12 Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmbH (2002) 54 IPR 344, 355 (FCFCA). 13 Woolly Bull Enterprises v Reynolds [2001] FCA 261, [40]; Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Philip Morris Ltd [No 2] (1984) 156 CLR 414. 14 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144. 15 Shell Co (Aust) Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Aust) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 601. 16 Colorado Group Ltd v Strandbags Group Pty Ltd (No 2) (2006) 69 IPR 281. 17 Koninklijke Philips Electronics NV v Remington Products (Aust) Pty Ltd (2000) 100 FCR 90. 3 212805252 …use of the mark as a "badge of origin" in the sense that it indicates a connection in the course of trade between goods and the person who applies the mark to the goods ... That is the concept embodied in the definition of "trade mark" in s 17 – a sign used to distinguish goods dealt with in the course of trade by a person from goods so dealt with by someone else.18 Use as a business name, in advertising or on the Internet will be sufficient, provided such use meets the definition of "use as a trade mark". In Australia, registration of a business name does not create any intellectual property rights and is not prima facie evidence that a sign has been used "as a trade mark". Regsitration is required by legislation to enable those who deal with a business to ascertain the identity of those trading under a particular name. In Shahin Enterprises Pty Ltd v Exxonmobil Oil Corporation [2005] FCA 1278, 73, Lander J held: There is a clear distinction, in my opinion, between conducting a business under a particular name and using a mark in respect of goods or services. The intention which the applicant needed to establish was an intention to use a mark to distinguish goods or services in the course of the applicant’s trade from goods or services provided by any other person. Because it has established that it intended to use the name to brand its businesses, that does not mean, however, it has established that it has used a mark or a sign to distinguish goods or services in the course of trade. Whether a person has used a sign that constitutes their business name as "a trade mark" depends on whether they have used it as a badge of origin. However, it is not uncommon for a business name to also be used as a trade mark. Use of a trade mark on the Internet, uploaded on a website outside of Australia, without more, is not use by the website proprietor of the mark in each jurisdiction where the mark is downloaded. However, if there is evidence that the use was specifically intended to be made in, or directed or targeted at, a particular jurisdiction, then there is likely to be a use in that jurisdiction where the mark is downloaded.19 Generally, use of a mark for merchandising will only amount to genuine use if that use is for the purpose of promoting the goods upon which the mark is applied. The context of use is all-important. Use of the movie title Startrek, registered for clothing and used on the front of a T-Shirt, will constitute genuine use of the mark for clothing if the mark is applied to distinguish those T-Shirts as emanating from a particular trade source owned or controlled by the trade mark owner. On the other hand, use of Startrek in a purely decorative fashion 18 Coca-Cola Co v All-Fect Distributors Ltd [1999] FCA 1721, 19. 19 Ward Group Pty Ltd v Brodie & Stone Plc (2005) 143 FCR 479, [43]. 4 212805252 will not constitute genuine use. In one case, a court held that use of the words "CHILL OUT" on the front of a T-shirt along with an image of a Coca-Cola bottle on licence from Coca-Cola was not genuine use of "CHILL OUT" as a trade mark. The reason was that the words were used to advertise the CocaCola beverage as a "suitable medium or accompaniment of relaxation", rather than to distinguish the T-shirts as originating from a particular trade source from other T-shirts from a different trade source.20 4. What degree of use is required for maintaining protection? Is token use sufficient? Is minimal use sufficient? There is no de minimis use requirement. A single bona fide use of the mark in the relevant period may suffice to defeat an application for removal.21 However, it has been said that in such cases the tribunal should require "if not conclusive proof, at any rate overwhelmingly convincing proof"22 and may not be persuaded by evidence that is solely from the internal files of the trade mark owner23 or of a circumstantial nature.24 Token use designed to maintain the trade mark registration is not sufficient. The use must be in good faith, meaning genuine commercial use.25 In the Gallo case,26 the importation and offering for sale of 144 bottles of wine in Australia was deemed genuine commercial use. The court found that the offering for sale or sale was for the purpose of profit and establishing goodwill in the registered mark and the use was neither fictitious nor colourable. 5. Is use in the course of trade required? Does use by non profit-organisations constitute genuine use? Does use in the form of test marketing or use in clinical trials constitute genuine use? Does use in [the] form of free promotional goods which are given to purchasers of other goods of the trademark owner constitute genuine use? Does internal use constitute genuine use? Use in the course of trade is required.27 Use must also be in good faith. Use by non profit organisations may constitute genuine use, provided that the mark is used as a trade mark (ie, used as an indication of trade origin).28 Use in the form of test marketing may constitute genuine use, but this will depend on the circumstances. As stated above, purely preparatory acts which 20 Top Heavy Pty Ltd v Killin (1996) 34 IPR 282. 21 See Estex Clothing v Ellis and Goldstein (1967) 116 CLR 254, 258. 22 "Nodoz" Trade Mark [1962] RPC 1 (Ch D); cited with approval in Estate Agents Co-op Ltd v National Assn of Realtors (1988) 11 IPR 467, 475. 23 "Nodoz" Trade Mark [1962] RPC 1 (Ch D). 24 "Trina" Trade Mark [1977] RPC 131 (UK Reg). 25 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144. 26 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144. 27 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144, 163; see also Sports Warehouse Inc v Fry Consulting Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 664 at [166]. 28 Herron Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Brown (1998) 45 IPR 321, 327. 5 212805252 relate merely to planning to use a mark / investigating whether to use a mark (such as, for example, preliminary discussions with potential distributors) will not constitute genuine use.29 Use in the form of test marketing will constitute use if the trade mark owner can show evidence of a genuine commitment to using the mark, rather than acts which are purely preparatory to using the mark. For example, the use of a mark on brochures which were sent to a person who had agreed to distribute the given product was held to constitute genuine use.30 Clinical trials conducted for the purpose of obtaining regulatory approval will not constitute genuine use as the mark will not be used in the course of trade.Use of the mark on free promotional goods is unlikely to constitute genuine use, unless the supply of free samples is for the purpose of trade in those goods and the trade mark owner can show that the distribution of free samples was not merely a means to protect registration.31 For example, it has been held that the use of the trade mark "CSL" on CDROMs and databases supplied free of charge to promote vaccine / antigen products did not constitute genuine use of the trade mark on class 9 goods (ie, electronic instruments and computer software and hardware).32 However, distribution of free classified telephone directories bearing the mark constituted use of the mark on the basis that the publisher derived income from the sale of advertising in the directories.33 Use of a trade mark on the internal files and records of a company has been held to be insufficient to constitute genuine use,34 but this will likely depend on the facts of a given case. 6. What is the required geographic extent of use? Is use only in one part (or a state in the case of confederation) of the country sufficient? Is use of the CTM in only one EU member state sufficient? Is use only in relation to goods to be exported sufficient? Is use in duty free zones considered to be genuine use? In general, there is no required geographic extent of use in Australia. To defeat a non-use application, the trade mark owner is required to show use or good faith use in Australia. There is no legislative requirement that use must be in respect of every Australian State and Territory, and, if not, use of the challenged trade mark is liable to being confined to particular States and/or Territories. However, under section 102 of the Act, a non-use applicant may have boundaries imposed on the territorial scope of a challenged trade mark, provided: 29 Woolly Bull Enterprises v Reynolds [2001] FCA 261, [40]; ; Moorgate Tobacco Co Ltd v Philip Morris Ltd [No 2] (1984) 156 CLR 414. 30 Settef SpA v Riv-Oland Marble Co (Vic) Pty Ltd (1988) 10 IPR 402, 418. 31 M Davison, T Berger and A Freeman, Shanahan's Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off (4 ed, 2008) [5.3025]. 32 CSL Ltd v Hong Kong CSL Ltd (2008) 76 IPR 772, [26]. 33 Golden Pages Trade Mark [1985] FSR 27 (approved in Oakley Inc v Franchise China Ltd [2003] FCA 105). 34 "Nodoz" Trade Mark [1962] RPC 1 (Ch D). th 6 212805252 (a) the non-use applicant is the owner of a registered trade mark, which is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the challenged mark and which is subject to a limitation to a specified territory or for export to a specified market; or (b) the Registrar or a court is of the opinion that the applicant may properly obtain registration of a trade mark with that limitation. If the Registrar or court is satisfied there has been no use of the challenged trade mark for three years (and the non-use application is commenced five years after the filing date of the challenged trade mark), then the Registrar or court may make the challenged trade mark subject to limitations to a specified territory or for export to a specified market. We are aware of only one decision (an Australian Trade Marks Office decision) in which section 102 was considered,35 and that case found the section inapplicable on the facts. Use in only one part of Australia is sufficient, unless the provisions of section 102 (just discussed) apply. Use only in relation to goods to be exported is sufficient.36 There is no provision that use in a duty free zone is not use in "Australia". Accordingly, use in duty free zones is considered to be genuine use. 7. Does genuine use have to take place in the exact form in which the mark is registered? Is use in a different form sufficient? What difference is considered permissible? What if (distinctive) elements are added or omitted? Is use of a mark in black and white instead of colour sufficient (in case of marks with a colour claim) and vice versa? Genuine use does not have to take place in the exact form in which the mark is registered. Certain "additions or alterations" to the registered mark are permitted, provided that they do not "substantially" affect the mark's identity.37 The question of whether an addition or alteration substantially affects a mark's identity depends on the facts. For example, it has been held that: o omission of the word "Service" from the registered trade mark "FunjetService" was not a substantial alteration in the context of travel agency services;38 and o use of the word "MINDGYM" constituted use of a registered trade mark composite trade mark consisting of "MINDGYM" word and a distinctive device comprising a rounded striped rectangle encompassing a skull shape, because the word "MINDGYM" itself (rendered in distinctive font) was the key element in the mark.39 35 I Can't Believe It's Yoghurt Ltd v Unilever Plc (2001) 55 IPR 207. 36 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 228. 37 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) ss 100(2)(a) and 100(3)(a). 38 QH Tours Ltd v Mark Travel Corp (1999) 45 IPR 553 (Reg). 39 Matzka v The Mind Gym Ltd [2006] ATMO 14. 7 212805252 In the Gallo case,40the High Court held that there was use of the word mark BAREFOOT notwithstanding that the word BAREFOOT always appeared in close conjunction with the image of a bare foot. By contrast, a much stricter test was applied in a decision that the removal of the hyphen from the registered trade mark "Ugh-Boots" was held to be an alteration which substantially affected the identity of the trade mark, such that the use of "Ugh Boots" or "Ugg Boots" did not amount to use of the registered trade mark.41 A trade mark which is registered without limitations as to colour is taken to be registered for all colours under section 70(3) of the Act, and therefore use of a mark in colour will constitute use of the black and white registered mark. 8. Does the mark have to be used in respect all of the registered goods and services? What if mark is used in respect of ingredients and spare parts or after sales services and repairs, rather than registered goods and services? What is the effect of use which is limited to a part of the registered goods or services? What is the effect of use limited to specific goods or services? There must be an intention to use, and actual use of, the mark in relation to the goods and services specified in the trade mark registration. Non-use in relation to some of the registered goods and services may be grounds for an application for partial removal from the register.42 As a general rule, proof of use of a trade mark on goods and services other than those for which the trade mark is registered will not rebut an allegation of non-use.43 However, in an application for non-use, the Registrar has a discretion not to remove a trade mark even if non-use in relation to the registered goods and services has been established.44 Use of the mark in relation to ingredients and spare parts or after sales services and repairs (if those ingredients, spare parts or services are "similar goods or closely related services" or "similar services or closely related goods") rather than use in relation to the registered goods and services is relevant to the exercise of the Registrar's discretion to allow an unused mark to remain on the Register.45 Also relevant to the Registrar's discretion is whether, though unused, the mark is nonetheless well known because of some "residual reputation" from earlier use, or from overseas advertising and publicity.46 Where use is limited to a part of the registered goods or services, there may be grounds for a partial non-use action in respect of those goods or services 40 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144. 41 McDougall v Deckers Outdoor Corporation [2006] ATMO 5. 42 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 92(4). 43 Sustainable Agriculture & Food Enterprises Pty Ltd v Samaritan Pharmaceuticals Inc [2008] ATMO 97 (8 December 2008). 44 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 101(3). 45 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 101(4). 46 th M Davison, T Berger and A Freeman, Shanahan's Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off (4 ed, 2008) [70.2505]; "Hermes" Trade Mark [1982] RPC 425 (Ch D). 8 212805252 for which the mark is not used. If a partial non-use action is successful, the Registrar may narrow the scope of the specification to exclude the goods or services in relation to which the mark is not being used. However, in Nordstrom Inc. v. Starite Distributors Pty Ltd,47 the Hearing Officer allowed the NORDSTROM mark to remain registered in relation to "manchester" despite the fact that the registered owner had established use of the mark only in relation to towel products, bath mats and face washers. The decision was made on the basis of the Registrar's discretion under sub-section 101(3) of the Act on the basis that such goods were usually sold under the same trade mark and confusion was likely to occur if the goods within the description "manchester" are divided up amongst a number of producers. 9. Evidence of use: How does one prove genuine use? Is advertising material sufficient? Are sales figures sufficient? Is survey evidence required? Are the acceptable specimens for proving genuine use different for goods and services? Who has burden of proof for genuine use? Evidence of use usually takes the form of sales revenue and advertising expenditure for the relevant period supported by examples of orders, invoices, receipts, shipping documents, packaging, labels, website printouts, signage, advertising and promotional materials such as print advertisements and promotional articles, preferably bearing dates within the relevant period. Survey evidence is not required to establish use of a mark to defeat a non-use application. Generally, survey evidence would not be appropriate as evidence of a relatively small amount of use will suffice. Generally, acceptable specimens for proving genuine use may be the same for goods and services although use in relation to services would not include labels, packaging, etc. It has been held that "the fewer the acts [of use] relied on, the more solidly [these acts] ought to be established" or that "overwhelmingly convincing proof" is required if a single transaction is relied upon.48 Evidence of sales (eg invoices or the amount of tax paid) may be sufficient to establish genuine use.49 It has been held that evidence of web pages bearing a given trade mark, or notices advertising services associated with the trade mark, must be dated within the relevant period in order to constitute evidence of genuine use.50 Importantly, in a non-use application, the owner of the challenged trade mark bears the onus to establish genuine use of the trade mark during the relevant period.51 47 [2006] ATMO 89 (30 November 2006). 48 Ibid. New footnote Converse Inc v Kabushiki Kaisha Moonstar [2010] ATMO 87 49 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144, 169. 50 Matzka v The Mind Gym Ltd [2006] ATMO 14. 51 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 100(1). See, eg, Kowa Company Ltd v NV Organon (2005) 223 ALR 27, 37. 9 212805252 10. If the trademark owner has a proper reason for not having put his mark to genuine use, will he be excused? What constitutes a proper reason for nonuse? If the non-use is excusable, is there a maximum time limit? If so, is the time limit dependant upon the nature of the excuse? The trade mark owner may rebut an allegation of non-use in the relevant three year period52 by establishing that the failure to use the trade mark during the relevant period was "because of circumstances (whether affecting traders generally or only the registered owner of the trade mark) that were an obstacle to the use of the trade mark during that period".53 At the very least, the circumstances justifying non-use must: (i) arise externally to the registered owner; (ii) be circumstances of a trading nature; and (iii) have a causal link to the mark's non-use.54 The following circumstances have been held not to constitute an obstacle to use of a trade mark: (i) product packaging defects;55 (ii) the incapacity of the trade mark owner, whether financial or because of illness;56 (iii) the issue of cancellation proceedings in relation to the registration;57 (iv) transport and distribution problems); (v) the delay in the production of product labels;58 (vi) the conduct of clinical trials to investigate possible alternative uses of a pharmaceutical product;59 and (vii) lack of manufacturing facilities for the product.60 The following circumstances have been held to constitute an obstacle to use of a trade mark: 52 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 92(4)(b). 53 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 100(3)(c). 54 Woolly Bull Enterprises v Reynolds [2001] FCA 261, [45], [55]. 55 Nature's Remedy Australia Pty Ltd v Nature's Remedy Pty Ltd [1999] ATMO 47. 56 Woolly Bull Enterprises Pty Ltd v Reynolds (2001) 51 IPR 149. 57 Unilever Australia Ltd v Karounas (2001) 52 IPR 631. 58 P & T Basile Imports Pty Ltd v Societe de Produits Nestle [2001] ATMO 16. 59 Kowa Co Ltd v NV Organon (2005) 66 IPR 131. 60 Angioblast Systems Incorporated v UCP Gen Pharma AG [2010] ATMO 53. 10 212805252 (i) the imposition of post-war import restrictions preventing importation of milking machines;61 (ii) delays in obtaining health department approval for a pharmaceutical product;62 (iii) the need to conduct research and trials in relation to pharmaceutical products;63 and (iv) a long history of litigation in relation to the trade mark.64 There is no prescribed time limit for excusable non-use. 11. Within which period of time does use have to take place? If the trade mark owner had no intention in good faith to use, authorise the use of or assign the trade mark and there has been no use or good faith use at any time in the lead up to one month prior to removal, the trade mark may be removed from the Register. The trade mark may also be removed from the Register if there has been no use or no good faith use for a continuous three year period and the removal application is made five years after the filing date (which is also the registration date in Australia). 12. Does use of the mark by licensee or distributor constitute genuine use for maintaining protection? If so, does the license have to be registered? If so, are there any requirements to be met by the trademark holder (the licensor) to maintain the trademark (e.g. quality controls, inspections or retaining a contractual right to control or inspect)? Use of a registered trade mark by a licensee or distributor constitutes genuine use for maintaining protection, provided that use by the licensee or distributor is an "authorised use". Section 8 of the Act provides that a person is an authorised user of a trade mark if the person uses the trade mark in relation to goods or services under the control of the owner of the trade mark.65 Section 8 then provides that "quality control" constitutes the necessary control:66 If the owner of a trade mark exercises quality control over goods or services: 61 Aktiebologet Manus v RJ Fullwood and Bland Ltd (1949) 66 RPC 71. 62 Pierre Fabre SA v Marion Laboratories Inc (1986) 7 IPR 387. 63 Upjohn Co v Sanofi (1998) 42 IPR 576. 64 Natural Selection Clothing Co Ltd v Doyle [2001] ATMO 23; Lomas v WM Productions Pty Ltd [2005] ATMO 57 (in obiter). 65 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 8(1). 66 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 8(3). 11 212805252 (a) and dealt with or provided in the course of trade by another person; (b) in relation to which the trade mark is used; the other person is taken, for the purposes of subsection (1), to use the trade mark in relation to the goods or services under the control of the owner. Section 8 then provides that financial control will constitute control: If: (a) a person deals with or provides, in the course of trade, goods or services in relation to which a trade mark is used; and (b) the owner of the trade mark exercises financial control over the other person’s relevant trading activities; the other person is taken, for the purposes of subsection (1), to use the trade mark in relation to the goods or services under the control of the owner. However, "quality control" and "financial control" are not exhaustive definitions of "under the control".67 An authorised use of a trade mark by a person (see section 8) is taken, for the purposes of the Act, to be a use of the trade mark by the owner of the trade mark.68 While in general control must be actual and there is obiter that a mere contractual power to control (in the absence of the exercise of that power) may not be sufficient,69 Australian courts have taken a fairly liberal approach to the authorised use provisions.70 For example, a finding of authorised use was made notwithstanding that the registered owner was deceased during the relevant use period.71 In the context of authorised use of licensees, the High Court has held that:72 the essential requirement for the maintenance of the validity of a trade mark is that it must indicate a connexion in the course of trade with the registered proprietor, even though the connexion may be slight, such as selection or quality control or control of the user in the sense in which a parent company controls a subsidiary. Use by either the registered proprietor or a licensee (whether registered or otherwise) will protect the 67 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 8(5). 68 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 7(3). 69 CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd (2000) 52 IPR 42, [69]; M Davison, T Berger and A Freeman, Shanahan's th Australian Law of Trade Marks and Passing Off (4 ed, 2008) [80.505]. 70 R Burrell and M Handler, Australian Trade Mark Law (2010) 293. 71 CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd (2000) 52 IPR 42. 72 Pioneer Kabushiki Kaisha v Registrar of Trade Marks (1977) 137 CLR 670, 683 (Aicken J). 12 212805252 mark from attack on the ground of non-user, but it is essential both that the user maintains the connexion of the registered proprietor with the goods and that the use of the mark does not become otherwise deceptive. Conversely registration of a registered user will not save the mark if there ceases to be the relevant connexion in the course of trade with the proprietor or the mark otherwise becomes deceptive. This statement was approved in Yau's Entertainment Pty Ltd v Asia Television Ltd.73 In that case, the licensee's entitlement to use trade marks was referable to the licensing arrangements, one of the terms of which was that title selections were subject to ATVE's approval. This provided a sufficient connection in the course of trade with the registered proprietor. In the recent Gallo case, the High Court held that authorised use of a mark on goods by an overseas authorised user, which goods were then offered for sale and sold in Australia, constituted use of that mark in Australia. 74 If the trade mark owner is unable to demonstrate control of the licensee or use of its registered trade mark, the trade mark may be removed from the Register for non-use75 or pursuant to an application to the court for rectification of the Register.76 The fairly liberal approach to the authorised use provisions notwithstanding, it is advisable that trade mark licensors in Australia ensure that written licensing arrangements are in place and ownership and licensing arrangements are made clear to consumers of goods or services supplied under licensed trade marks. Otherwise, the necessary element of control may be absent. In HealthWorld Ltd v Shin-Sun (Aust) Pty Ltd,77 the court found that control was absent on the basis of the following facts, among others: (a) the absence of a written licence agreement; (b) the product labelling never displayed the name of the trade mark owner and associated the product exclusively with the licensee. Trade mark licences do not have to be registered with the Australian Trade Marks Office. Although this was a requirement under the predecessor to the current Act, namely, Trade Marks Act 1955 (Cth). In practice, it is uncommon to register trade mark licences. There are requirements to be met to maintain the trade mark, as discussed above, namely quality control which may be proved by contractual control and inspection powers as well as actual inspections. 73 (2002) 54 IPR 1. 74 E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144, [52]. 75 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 92. 76 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 88(2)(c). 77 (2008) 75 IPR 478. 13 212805252 13. What are the consequences if a mark has not been put to genuine use? Who may apply for a cancellation and in what circumstances? Is a defendant in opposition proceedings entitled to challenge the opponent and demand proof of genuine use of the earlier mark? If so, under what circumstances? If a trade mark has not been put to genuine use, an independent party may apply to have the trade mark expunged from the Register for non-use. If this non-use application is unopposed, the Registrar must remove the trade mark from the Register.78 Other events which may lead to removal or cancellation of a trade mark include: (i) removal by the Registrar;79 (ii) removal for non-payment of a renewal fee;80 (iii) cancellation upon request of the registered owner;81 and (iv) removal by court order on the application of an aggrieved person or the Registrar.82 If a non-use application is opposed, the Registrar has a discretion to: • remove the trade mark from the Register, in relation to any or all of the goods and / or services to which it relates; or • allow the trade mark to remain on the Register even if grounds for removal have been made out, if it is reasonable to do.83 Any person may apply to the Registrar of Trade Marks to have a particular trade mark expunged from the Register for non-use.84 It is no longer required that the applicant be a "person aggrieved".85 A non-use application can be brought in relation to any or all of the goods / services contained in the specification for a given mark.86 A non-use application against a challenged registered trade mark can be made on one or both of the following grounds:87 78 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 97. 79 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 84A. 80 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 78. 81 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 84. 82 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) ss 85-88 and ss 86-88A. 83 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 101. 84 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 92(1). 85 Trade Marks Amendment Act 2006 (Cth) s 46. 86 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 92(2)(b). 87 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 92. 14 212805252 (a) at the time when the application for registration was filed the applicant had no intention in good faith to use the trade mark in Australia, to authorise its use by another, or to assign it to a body corporate, and the trade mark had not been used up to 1 month before the removal application was made; or (b) the trade mark was registered for a continuous period of 3 years and 1 month before the date of the removal application, it had not been used in good faith in Australia on the goods or services in respect of which it was registered, and the removal application was made on or after the 5 year anniversary of the filing date of the application for registration of the challenged trade mark. A defendant (ie, the trade mark applicant) in opposition proceedings may challenge the opponent to registration by making a non-use application by means of a separate proceeding. In that non-use application, the defendant may plead that the opponent did not use an earlier registered trade mark, which mark forms one of the bases on which the opponent opposes registration. In such circumstances, it may be possible for the opposition proceedings to be suspended pursuant to regulation 5.16 of the Trade Mark Regulations pending the outcome of the non-use proceeding. Although the Registrar has no express power to suspend or temporarily stay opposition proceedings,88 the courts have held that the Registrar may do so for "proper reasons",89 such as to await a court's resolution of disputed facts that may be relevant to the opposition proceeding.90 We consider that "proper reasons" for suspension of opposition proceedings include non-use applications challenging earlier marks on which an opponent relies in its opposition. 14. Assuming a trade mark owner has not made genuine use of his mark within the prescribed period, can he cure this vulnerable position by starting to use in a genuine way after this period and will he then be safe against requests for cancellation or revocation? Is it allowed to re-register a trade mark that has not been genuinely used in the prescribed period of time? A trade mark owner who has not made genuine use of its mark within the prescribed period can cure this vulnerable position by starting to use the mark in a genuine way, provided no one files a non-use application within one month of the trade mark owner resuming or commencing use of the registered trade mark. The trade mark owner cannot re-register a lapsed mark and must file a fresh trade mark application. II. Proposals for adoption of uniform rules 88 Cadbury UK Ltd v Registrar of Trade Marks (2008) 77 IPR 608, 611. 89 Ibid. 90 Ibid. 15 212805252 The Groups are invited to put forward proposals for adoption of uniform rules as concerns the requirement of genuine use for maintaining protection. More specifically, the Groups are invited to answer the following questions: 15. What should the purpose of the uniform rules be? Should the rules address either or both purposes of protecting the consumers from confusion and of keeping the register uncluttered for new/potential trademark registrants? The purpose of the Uniform Rules should be to advance the functions of trade marks and the function of maintaining uncluttered trade mark registers. Burgunder has described the functions of trade marks as:91 (i) to enable consumers to discriminate efficiently among similar products in the marketplace with minimal private and social costs (Distinguishing Function); (ii) to preserve the goodwill of traders (and, hence, foster incentives for traders to offer quality goods and services) (Goodwill Function); and (iii) to allow consumers to associate goods or services in the marketplace with certain forms of information expressed in advertising (Advertising Function). Without public use of a trade mark, that trade mark: (i) will not serve the Distinguishing Function because consumers will not have developed any association between the trade mark and a particular good or service; (ii) will not serve the Goodwill Function because traders will not have developed any goodwill in that trade mark; and (iii) will not serve the Advertising Function because consumers will not have developed any associations between the trade mark and useful advertising information (eg, price, source, ingredients, quality, characteristics, etc). Further, without public use of a trade mark, a trade mark owner may "trademark-squat" certain trade marks, the use of which other traders are considering, but which other traders discount on the basis of trade mark registry searches. However, we do not consider the above functions justify or necessitate the introduction of a de minimis threshold. First, these policy considerations must be balanced against a trade mark owner's right to undertake an orderly, and commercially viable, expansion of use of the trade mark.92 Second, provided use is genuine, the above functions will be met to some degree—it is not the 91 Lee B Burgunder, 'An Economic Approach to Trademark Genericism' (1985) 23(3) American Business Law Journal 391, 396. 92 Ann Dufty and James Lahore, Patents, Trade Marks & Related Rights (2006) [57,555]. 16 212805252 job of non-use provisions to police use of trade marks to ensure that this use fulfils the above functions to a certain minimum degree. Third, where the onus for proving genuine use rests on the trade mark owner,93 self-policing by trade mark owners of their use of the mark is promoted. Accordingly, the purpose of the Uniform Rules on genuine use should be twofold: (i) to ensure registered trade marks have the functions outlined above without prejudicing the legitimate rights of trade mark owners to undertake orderly expansions of use of the trade mark; and (ii) to ensure that trade mark registers provide third parties with an accurate understanding of trade marks in current active use and prevent cluttering up of the register. The Australian Group considers that the existing Australian legal framework meets these policy objectives. However, if this legal framework is considered problematic, a solution may be to provide for shorter registration periods to encourage trade mark owners to consider trade mark renewal on a more regular basis, rather than imposing the substantial burden of up front filing of proof of use. We note that, in Australia, the legal elements of establishing non-use under section 92 of the Act are not concerned with preserving the functions of trade marks outlined above (which may also be cast in terms of protecting consumers from confusion). For example, the goodwill in a trade mark is not relevant to establishing use: as noted in the answer to 4 above, a single bona fide use of the mark may suffice. However, these functions may be considered by the Registrar in the exercise of his or her discretion not to remove an unused trade mark under sections 101(3) and 101(4) of the Act. 16. Should there in your opinion be a threshold to the “genuine use”, such as a de minimis rule for a trade mark? If so, what would be suitable threshold? Should the rule be construed differently for large co-operations than for small businesses? We consider a de minimis rule to be unnecessary. Genuine use is genuine use irrespective of the amount of such use. The current position under Australian law is noted in the answer to question 2 above, namely, use is sufficient if the trade mark has gone beyond investigating whether to use the mark and beyond planning to use the mark and has got to the stage where the trade mark owner can be seen objectively to have committed itself to using the mark, ie, to carrying its intention to use the mark into effect.94 We consider this to be a suitable threshold. We do not consider that any threshold of use rule should be construed differently for large co-operations than for small businesses because of 93 As under Australian law: see answer to question 9 above. 94 Woolly Bull Enterprises v Reynolds [2001] FCA 261, [40]. 17 212805252 enforcement difficulties and because such rules may create uncertainty for business. 17. To what extent should it be possible to use a mark that differs from the representation in the register and maintain protection? Should it even be possible to add or omit elements of a registered figurative mark and maintain the trademark? How should the system ensure that registers are reliable for third parties and yet provide some flexibility for the trademark holder when using the mark in commercial activities? We agree with the position as it currently stands under Australian law, namely, a trade mark owner may use a mark that differs from the representation in the register, provided the trade mark used does not substantially affect the identity of the registered trade mark. Our reason is that this position strikes a fair balance between maintaining the accuracy of the register (to serve the function of providing third parties with an accurate picture of registered trade marks) and the practical difficulties of the trade mark owner ensuring that all marketing conducted uses the trade mark in exactly the same form as the registered form. The current position also allows trade mark owners to make minor updates and revisions to the registered mark over time without incurring the expense of filing new trade mark applications. However, we also consider that further empirical research into the actual "clutter" on the Australian Trade Marks Register would be advantageous. Such research could draw lessons from studies conducted in the United States prior to the Trademark Law Revision Act 1988 which estimated that 23% of registrations over six years old reprsented unused "deadwood".95 18. Should the requirement of genuine use deemed to be met if the use is limited to one product or service out of several registered? Is it in your opinion reasonable that a trademark holder can “block” an entire product category by using the mark for only one type of product within the category? If not, what kind of standard should be adopted? The requirement of genuine use should not be deemed to be met if the use is limited to one product or service out of several registered. Under Australian law, if a registered trade mark is used in relation to just one product or service among several registered, the trade mark owner risks facing a partial non-use action in respect of the products or services in the specification in relation to which the trade mark is not used.96 We do not consider it reasonable that a trade mark holder can "block" an entire product category by using the mark for only one type of product within that category. We consider that the standard currently in place under Australian law (as described in question 8 above) is adequate. 19. What would be a suitable grace period for genuine use? 95 Trademark Review Commission Report (1987) 77 Trademark Reporter 375, cited in L Bently and R Burrell, 'The Requirement of Trade Mark Use' (2002) 13 AIPJ 81, 181-2, 185-8. 96 For further details, see our answer to question 8 above. 18 212805252 We consider that the period of non-use allowed under Australian law, namely three years, is suitable with removal actions only able to be made 5 years after the filing date of the application for registration of the mark.97 20. What circumstances should justify non-use? Should different criteria apply for different industry sectors (e.g. pharmaceuticals and other industries where authorities typically require particular market approvals which could delay the use of a trademark)? Should the criteria be more stringent the longer the period of non-use is? We agree with the current position under Australian law that non-use is justified by "circumstances (whether affecting traders generally or only the registered owner of the trade mark) that were an obstacle to the use of the trade mark during that period".98 An example would potentially be the current Australian Government plans to introduce legislation by 1 July 2012 requiring plain packaging for tobacco products. There may be some value in providing a non-exhaustive list of specific circumstances that would excuse non-use. We do not consider that different criteria should apply to different industries. We do not consider it desirable to stipulate more stringent criteria for longer periods of non-use. If the non-use is genuinely excusable (ie, it was, inter alia, caused by obstacles of a trading nature external to the trade mark owner),99 then the duration of the non-use should not be a relevant criterion. In any event, this concern is addressed by the fact that the longer the period of nonuse, the more difficult it will be for the trade mark owner to prove the necessary causal link between the obstacle and the non-use. 21. Should any use of a trademark by entitled third parties be attributed to the proprietor? Should there be a difference between licensees and independent distributors and will registration of a license be necessary? Use by an entitled third party should only be attributed to the proprietor where that use meets the requirements of "authorised use" under the law as described in the answer to question 12 above. Australian law requires use by entitled third parties to be under the control of the owner of the trade mark. In this way, the law meets the policy objective of ensuring that consumers will be able to properly assume that a good or service offered under that trade mark is controlled by a particular trader. In other words, the quality control requirement ensures that the trade mark, once licensed, continues to signify the origin of the quality of the relevant good or service. Provided the necessary control element is met, the law should not stipulate different criteria for authorised use of a licensee as opposed to an independent distributor. Similarly, registration of a licence should not be necessary if the requisite element of control by the trade mark owner is present. 97 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 93(2). 98 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 100(3)(c). 99 See our answer to question 10 for further detail. 19 212805252 22. Should there be an exception from the genuine use requirement in some cases ? The capacity to register "defensive trade marks" under section 185 of the Act constitutes such an exception. Under section 185 of the Act, a trade mark owner can register a "defensive trade mark" in respect of goods or services in relation to which it does not or does not intend to use its mark. In order to obtain registration of a defensive trade mark, an applicant must show that one its registered trade mark has been used so extensively in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered, that its use in relation to other goods or services will be taken to indicate that there is a connection between those other goods or services and the applicant.100 We consider that "defensive trade marks" and genuine obstacles to use discussed in our answer to question 10 above should constitute the only exceptions to the genuine use requirement. 23. Should there be uniform rules addressing the issue whether the cancelled trademark should be eligible for re-registration immediately upon the cancellation decision? Should other parties’ interests than those of the new registrant be taken into account, e.g. consumers’ interests in avoiding confusion as to the nature and quality of goods and services that might be expected under a particular mark? We do not consider it necessary to have specific rules relating to the reregistration of marks following their removal from the Register for non-use. We understand that one purpose of such rules would be to avoid the "clutter" created on the Register by re-registration of removed marks by their former owners, which marks they do not intend to use. However, we consider that this purpose would be better served by a requirement to file proof of use (as is the case in the United States and the Philippines). Another purpose may be to avoid prejudicing the former trade mark owner in the event that that person intends to overcome the cancellation or removal decision. This concern is addressed by the fact that the trade mark owner may appeal any cancellation or removal decision and the trade mark will not be cancelled or removed until a final court order has been made and all avenues of appeal exhausted. Interests of parties other than the applicant for a cancelled or removed mark should and, under Australian law, are taken into account. In theory, if there has been no use of the expunged mark, then re-registration should not entail a risk of consumer confusion. Under Australian law, the Registrar must reject a trade mark application if satisfied that certain statutory grounds for rejection are met, including, most relevantly, if: 100 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 185(1). 20 212805252 (a) the use of the trade mark would be contrary to law,101 including consumer protection law under which misleading or deceptive conduct is proscribed;102 or (b) the use of the trade mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.103 In addition, third parties, including the former trade mark owner, may oppose the application for an expunged mark on statutory grounds, including, most relevantly, in addition to those mentioned above, the following: (a) the applicant is not the owner of the trade mark;104 (b) the trade mark is similar to a trade mark that has acquired a reputation in Australia;105 or (c) the application was made in bad faith.106] We consider the above provisions in Australian trade mark law address the issues raised by this question. 101 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 42(b). 102 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, s 18. 103 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 43. 104 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) sub-s 58. 105 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 60. 106 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) s 62A. 21 212805252 Summary In Australia, genuine use is a requirement for maintaining protection. While there is no formal requirement that Australian Trade Mark registration owners must lodge proof of use or the like on a periodic basis, an Australian Trade Mark registration is vulnerable to being expunged or being endorsed with limitations as a result of a non-use application by any person. Genuine use requires use in good faith, as a trade mark, in the course of trade, in Australia, upon or in relation to the goods and / or services and by the trade mark owner, predecessor in title or an authorised user. The use may be in a form different to the registered form, provided that the form in use does not substantially affect the identity of the registered form. If the owner's good faith intention to make genuine use of the mark is not in question, the mark is vulnerable to expungement on the ground of lack of good faith use for a continuous three-year period. However, genuine obstacles to use may excuse non-use. The Australian Group considers that the existing Australian legal framework meets the policy objectives of the genuine use requirement, namely: a) a public register that provides an accurate picture of registered trade marks in active use; and b) ensuring registered trade marks perform their functions as trade marks without prejudicing the legitimate rights of trade mark owners to undertake orderly expansions of use of their registered marks. Résumé En Australie, l’usage sincère est une nécessité pour le maintien de la protection. Alors qu’il n’est pas exigé de façon formelle que les propriétaires d’un enregistrement de Marque Déposée Australienne doivent fournir périodiquement la preuve de l’usage ou équivalent, l’enregistrement d’une Marque Déposée Australienne peut être supprimé ou être assorti de restrictions suite à une demande pour non-usage faite par quiconque. L’usage sincère exige l’usage en toute bonne foi, comme marque, dans le cadre commercial, en Australie, sur ou en lien avec les marchandises et/ou services, et ce par le propriétaire de la marque, le prédécesseur en titre ou un utilisateur habilité. Cet usage peut prendre une forme différente de la forme déposée pourvu que la forme utilisée n’affecte pas en substance l’identité de la forme déposée. Si l’intention de bonne foi du propriétaire de faire un usage sincère de la marque n’est pas en cause, la marque peut être supprimée au motif d’absence d’usage de bonne foi pendant une période de trois années consécutives. Cependant, de véritables obstacles à l’usage peuvent excuser le non-usage. Le Groupe Australien considère que le cadre juridique australien existant répond aux objectifs stratégiques de l’exigence d’usage sincère, à savoir: 22 212805252 a) un registre public qui fournit une image exacte des marques déposées enregistrées activement utilisées ; et b) assurant que les marques déposées enregistrées remplissent leurs fonctions en tant que marques déposées sans porter atteinte aux droits légitimes des propriétaires de marques déposées d’entreprendre des extensions en ordre de l’usage de leurs marques déposées. Zusammenfassung In Australien stellt die ernsthafte Benutzung eine Voraussetzung zur Aufrechterhaltung des Schutzes dar. Auch wenn es kein formelles Erfordernis gibt, dass Besitzer eingetragener australischer Handelsmarken regelmässig Benutzungsnachweise oder Vergleichbares einreichen müssen, sind eingetragene australische Handelsmarken dennoch gefährdet, als Folge einer Beschwerde wegen Nichtbenutzung durch beliebige Personen gelöscht zu werden oder Begrenzungen zu erfahren. Ernsthafte Benutzung erfordert die gutgläubige Nutzung als Handelsmarke im gewöhnlichen Geschäftsverlauf in Australien auf oder in Beziehung zu Gütern und / oder Dienstleistungen durch den Besitzer der Handelsmarke, den Rechtsvorgänger oder einen bevollmächtigten Nutzer. Die Benutzung kann in einem Format geschehen, das nicht dem eingetragenen Format entspricht, sofern das Format die Identität des eingetragenen Formats nicht erheblich in Mitleidenschaft zieht. Falls die gutgläubige Absicht des Besitzers, die Marke ernsthaft zu benutzen, ausser Frage steht, besteht für die Marke die Gefahr der Löschung aufgrund mangelnder gutgläubiger Nutzung während eines durchgehenden Zeitraums von drei Jahren. Ernsthafte Hindernisse bezüglich der Benutzung können allerdings die Nichtbenutzung entschuldigen. Die australische Gruppe ist der Ansicht, dass das vorhandene australische gesetzliche Regelwerk den grundsätzlichen Zielen des Erfordernisses ernsthafter Benutzung entspricht, da a) ein öffentliches Register existiert, das ein präzises Bild der eingetragenen Handelsmarken in aktiver Benutzung vermittelt, und b) sichergestellt wird, dass Handelsmarken ihre Funktionen erfüllen, ohne die legitimen Rechte von Handelsmarkenbesitzern zu beeinträchtigen, eine systematische Erweiterung der Benutzung ihrer eingetragenen Marken zu betreiben. 23 212805252