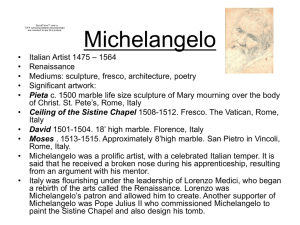

Michelangelo -- Volunteer Presentation

advertisement

1. Portrait of Michelangelo, unfinished, by Jacopino del Conte ca. 1540, oil on wood, 34 ¾” x 25 ¼”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY The Victory, ca. 1532-1534, 8’ 7 1/2”, marble, Sala dei Cinquecento, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence Michelangelo used his own features as the old man who is bound and bent beneath the left knee of the dominating figure of The Victory. Image from The Last Judgment, 1536-1541, wall fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome Michelangelo used his features for the flayed skin held by St. Bartholomew in The Last Judgment fresco painting on the wall of the Sistine Chapel. The Deposition [also known as The Nicodemus Pietà] , ca. 1540-1555, 7’ 8”, marble, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence Michelangelo created his image as Nicodemus in The Deposition [also known as The Nicodemus Pietà]. In this sculpture, Nicodemus hands down the body of Christ to the Virgin Mary and to Mary Magdalene. There were a few artists who created portraits of Michelangelo, both during and after his lifetime. One of these artists was Jacopino del Conte [1510 – 1598], a Mannerist painter who worked in both Florence and Rome. X-ray examination of this unfinished painting found that Michelangelo’s portrait had actually been painted over an earlier blocked in composition of the Holy Family, also by del Conte. Michelangelo evidently created three images of himself. He painted his features on the flayed skin held by the figure of St. Bartholomew in The Last Judgment fresco painted on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. He sculpted his own features on the face of old man who bends beneath the knee of The Victory sculpture in the Sala dei Cinquecento, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence as well as on the face of old Nicodemus in The Deposition [also known as The Nicodemus Pietà] sculpture in the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo [Cathedral] in Florence, Italy. 1 2. Mallet and chisels used to cut and shape the stone; A sculptor working on a stone sculpture photographs Michelangelo believed that each sculpture lived inside a block of stone until it was set free by the artist-sculptor. Here we see some of the tools that Michelangelo used and that are still in use today. The artistsculptor uses variety of mallets to pound the blades of different chisels against the stone’s surface. At first, a large mallet and chisel are used to remove chunks and fragments of stone which allows the rough shape to emerge. Once the intended shape is released from the stone, the artist-sculptor then uses increasingly smaller mallets and chisels to remove smaller bits of stone in order to carefully refine the final form as well as to create fine features and details. Finally, the artist-sculptor uses files, pumice, sandpaper, and cloths to smooth the stone’s final, polished surface. Michelangelo’s most-used tool was the serrated claw chisel, called the gradina. With this tool, Michelangelo was able to create both grooved and cross-hatched textures on the form as he carefully carved away the excess stone. Like the lines and cross-hatchings that he used to create form in his two-dimensional drawings, the grooved textures that Michelangelo carved with his gradina helped define the form of the sculpture that he slowly and skillfully “released” from the stone. Sometimes these textures would later be filed and smoothed away as the work progressed but often, they would remain just as Michelangelo originally created them, as a specifically textured surface. 2 3. Atlas by Michelangelo, ca. 1520-23, unfinished marble, 208 cm, approx. 6’ 10”, Galleria dell’ Accademia, Florence, Italy Young Slave by Michelangelo, ca. 1520-23, unfinished marble, 235 cm, approx. 7’ 8 1/2” Galleria dell’ Accademia, Florence, Italy In 1505, Pope Julius II commanded Michelangelo to come to Rome and design a memorial tomb for him. This was a project that would trouble Michelangelo for the next forty years until a smaller version of the tomb to commemorate Julius II was finally finished in1545 for the church of San Pietro in Vincoli [St. Peter in Chains Church] in Rome. Ironically, Pope Julius II was never buried in this tomb because he died in 1513, long before his memorial tomb was finished. Instead, his remains were interred in St. Peter’s Basilica next to the remains of his uncle, Pope Sixtus IV. These two marble statues are part of a group of four unfinished works that were originally intended to decorate one of the early versions of the Tomb for Pope Julius II. Michelangelo designed several versions of the tomb over the years because Julius’ family, the della Roveres, kept changing their minds as to what they wanted. Why these particular works remained unfinished is a mystery, but the likely reason is because their size and purpose no longer fit the revised plans for the Tomb. Fortunately, Michelangelo kept these works until he died and, after his death, they were installed in the Boboli Gardens of the Pitti Palace in Florence. They remained on display in the Gardens until 1909, at which point they were moved indoors to the Accademia, and they are now displayed in a hallway that leads to Michelangelo’s magnificent sculpture of David.. Because Michelangelo kept these unfinished sculptures, we can actually see how he approached his work. He first imagined the form that waited within the stone. Michelangelo said that, “every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.” He would next pick up his mallet and chisel to began chipping away somewhere in the middle of the piece of marble, carefully working his way upward, downward, and around the block of stone as he removed the excess marble in order to slowly reveal the form that awaited release. Michelangelo’s biographer, Vasari, described Michelangelo’s sculptural skill by saying that his sculptures emerged from the stone, “…as though surfacing from a pool of water.” 3 5. The Pietà 1499, marble, 5’ 9” high, 6’6” high, including base, St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome, Italy Besides designing the Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Michelangelo also created this favorite masterpiece that has been prominently displayed there for more than 500 years. When he was commissioned to create this statue of the Holy Mother and Christ, Michelangelo was just 24 years old. When the sculpture was put on display, it truly amazed all who saw it. The Pietà depicts the Holy Mother, Mary, who holds the crucified body of her dead son, Jesus, across her lap. She sits quietly, calmly accepting what has happened, yet her grief and anguish is still clearly communicated through the simple gesture that she makes with her left hand. Michelangelo created a stable, pyramidal [ triangular] form that is unusual because it is also asymmetrically balanced. Unity is created through the position of Christ’s arms and legs that bend and follow the graceful folds of Mary’s robe. The details carved into this sculpture are truly amazing: there are realistic skin folds and fingernails on the hands and toes, the strands of hair are arranged realistically, the chiseled patterns indicating the earth, and the many rippling folds of the garments—some folds are carved so thinly that the stone is translucent—all add such a sense of reality to this work. Although the body of Jesus is life-sized. Mary’s body is larger than life, well-proportioned, and clearly strong enough to hold Christ’s weight easily. If she were to stand up, she would be seven feet tall, yet her head is the same size as Christ’s. To the viewer, however, none of these inconsistencies are readily apparent; the visual effect is real and it is stunning. As Michelangelo said, “ It is necessary to keep one’s compass in one’s eyes and not in the hand, for the hands execute, but the eye judges.” Fun Fact: This was the only work that Michelangelo actually signed with his name. When he overheard someone attributing his sculpture to another artist, he quickly carved the words, “Michelangelo Buonarroti, Florentine, made this” onto the narrow band that falls across Mary’s chest. 4 6. David ca. 1501-1504, marble, 517 cm, approx.16’ 11 1/2”, Galleria dell’ Accademia, Florence, Italy Carved from a huge, piece of white marble that earlier sculptors had started working on and abandoned, the high point of Michelangelo’s early career was this successful and magnificent marble statue of “David.” Michelangelo won the commission to tackle the used piece of marble and to carve a statue of David in 1501. The statue was originally supposed to sit atop a wall that buttressed the Duomo, Florence’s Cathedral, but when it was finally displayed in September of 1504, the Florentine citizens instead enthusiastically embraced and adopted the statue as the symbol of their united defiance and independence because, at the time, Florence was facing imminent threats of war and conquest from other, nearby city-states as well as from France. So, instead of adorning the buttress wall, the “David” was installed in a place of honor in the Piazza della Signoria next to the entrance of Florence’s Town Hall, called the Palazzo Vecchio. Centuries later, in 1873, the “David” was moved inside for safety’s sake, to the nearby Galleria dell’ Accademia. Later, in 1910, a copy of the statue was installed at the original site on the Piazza della Signoria. “David” takes an asymmetrically-balanced, contrapposto stance with his weight carried on his right leg. He stands tense and alert, anticipating the imminent fight he will soon have with the Philistine giant, Goliath. Although “David” holds his sling in both hands with the strap draped loosely across his left shoulder and down his back, his weapon is ready to spin and launch a fatal stone in an instant. “David” frowns slightly as he intently gauges the next move of his foe, Goliath. He assesses the situation and calculates his own next move. He is ready… 5 7. David ca. 1501-1504, marble, 517 cm, approx.16’ 11 1/2”, Galleria dell’ Accademia, Florence, Italy Nearly 17 feet tall, Michelangelo’s “David” truly demonstrated his mastery of sculpture and his ability to create art from stone as he displayed his extensive knowledge of the human body. Unity is achieved by the overall smooth, three-dimensional realism of the carved marble figure. Michelangelo created amazing true-to-life details in the stone that clearly and accurately depict the muscles of the body and even “David’s” veins, fingernails, and toenails. “David’s” alertness and apprehension are both conveyed through the turn of his body, the tightness of the tendons in his neck, the grim expression of his mouth, and even in the uneasy scowl on his brow as he watches and awaits Goliath’s next move. 6 10. Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508 – 1512, fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome The Sistine Chapel is one of many chapels and buildings in the Vatican City, an independent citystate of the Catholic Church that is located within the city of Rome, Italy. Named for Pope Sixtus IV, the Sistine Chapel was built between 1477 and 1486. It was constructed upon the foundation of a much earlier Great Chapel and consequently its walls are not parallel. Many artists created a variety of original wall frescos and the original fresco ceiling consisted of a blue background with golden, gilded stars. In 1508, Michelangelo was commissioned—nay, commanded—by Pope Julius II to create a new fresco painting for the ceiling. Although Michelangelo preferred sculpture and did not want to paint, a rival, Bramante, evidently convinced the Pope to demand Michelangelo’s cooperation because Bramante secretly hoped that Michelangelo would surely fail. Bramante was proved wrong, however, and Michelangelo’s frescos on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling are among the finest pictorial images of all time! Michelangelo divided the vaulted ceiling into ceiling panels, corner spandrels, triangular pediments, and side-wall arched lunettes. The panels depict stories from the Book of Genesis in the Old Testament, from the Creation of the World and of Man, to Noah and the Flood. In the spandrels are four savior bible stories. The pediments depict seven male Old Testament Prophets and five female pagan Sibyls who all foretold of Christ’s coming. In the arched lunettes are the ancestors of Jesus. Each scene and all 343 colorful and mighty images together demonstrate Michelangelo’s skill and ability to depict in brilliant color, such beautiful sculptural forms and movement with a paint brush. Because the vault of the ceiling is 68-feet above the floor, Michelangelo also had to devise the unique scaffolding upon which he and his team of assistants could work safely. While some assistants applied the fresh plaster, or transferred cartoon drawings onto the plaster, others ground pigments and prepared the paints. Michelangelo did the painting and he did not paint the ceiling while lying down. The floor of the scaffold was far enough below the ceiling to allow everyone room to work and Michelangelo spent his days with his arm and brush stretched high above him as he constantly bent backward and looked upward in order to paint. He did this daily for four years, a painful and dedicated task! The ceiling is symmetrical and balanced. It is unified by its biblical theme, by its beautiful bright colors, and by its 343 human figures, all sculpturally depicted in graceful and lively positions. 7 11. Detail: The Creation of Adam, Sistine Chapel Ceiling, 1508 – 1512, fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome “The Creation of Adam” is one of the best-known images from the Sistine Chapel ceiling. In this panel, Michelangelo’s talent for creating three-dimensional, sculptural forms was translated into the two-dimensional shapes of God and Adam. Michelangelo used sculptural highlights and shadows to define the perfection of Adam’s “ideal” Renaissance figure in a reclining, contrapposto position. This image is unified by an overall repetition of colors and shading as well as by the continuous line created by Adam’s arm and hand as he reaches out to receive the give of life from God’s own outstretched arm and empowering fingertip. The focus of this painting is the imminent touch of their fingertips, a powerful focal point in this panel’s space that unites the two sides of the panel both literally and symbolically. 8 12. The Last Judgment, 1536 – 1541, wall fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome The Sistine Chapel, also included another masterpiece created by Michelangelo, and that is the fresco of The Last Judgment on the wall behind the Chapel’s altar. In 1536, Michelangelo was again commanded—this time by Pope Paul III—to complete the Sistine Chapel with a new fresco painting for the altar wall. Michelangelo had two windows removed and plastered over before he spent the next seven years completing his large and sometimes gruesome painting that was called, “The Last Judgment”. Filled with many religious signs and images as well as huge, muscular figures, Michelangelo portrayed the ultimate judgment of the souls of all mankind. The Resurrected Jesus Christ, with the Virgin Mary at his right side, sits in the upper center of the scene, surrounded by a group of martyred saints, each of whom holds the tools that were used to complete their martyrdom. Below them, angels blow on trumpets to awaken the dead and to announce that judgment is nigh. As Christ raises his hand in judgment, some souls rise up on one side of the scene and they ascend to their heavenly blessing and reward. But the souls on the other side are doomed and they slide, fall, or are dragged and bitten by demons as they descend into eternal hell and damnation. Michelangelo also included images taken from Greek myth and Dante’s Inferno with his depiction of the demon ferryman, Charon [Share on], who rowed the damned across Hell’s river, Styx [Sticks], and of Minos [My nos], the satanic Prince of Hades, who awaits the arrival of all condemned souls, In the top two arched areas are two groups of angels who carry instruments of Christ’s Passion and his suffering and death. We can see the cross and the crown of thorns, the column upon which Christ was beaten, the reed and sponge used to offer him vinegar, and the ladder down which the body of Christ was lowered after the crucifixion. 9 13. Moses, 1513– 1515, marble, 235 cm, approx. 7’ 8 ½”, San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome In 1505, Michelangelo was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II to design a magnificent, 3-story memorial Tomb for Julius. In 1506, however, Julius changed his mind and, instead, made Michelangelo paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. When Julius died in 1513, the family of Julius, the della Roveres, demanded that Michelangelo revise and reduce his plans for Julius’ Tomb. The revised Tomb was smaller, but it still included the sculpture of “Moses,” the stern and mighty leader of the Israelites, the man who met with God on the mountain top for forty days and nights, and who, with his face radiant and shining, brought down Stone Tablets upon which had been carved the Ten Commandments. Michelangelo completed his “Moses” sculpture in 1515, during an interval when other work on the Tomb had been halted. Michelangelo decided to keep the sculpture in his studio and eventually, in 1545, the “Moses” and two sculptures of Jacob’s wives “Rachel” and “Leah”, were finally installed for the completed Tomb of Julius II in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli [St. Peter in Chains] in Rome. Michelangelo’s interpretation of “Moses” forms a powerful, muscular, ever-vigilant, and stern leader. He sits in a twisting, active, contrapposto pose as he holds the Stone Tablets under his right arm and grasps the intricate coils of his beard in his hand. The horns on Moses’ head were the result of an early version of the Latin Bible that mistranslated a Hebrew word meaning “radiant” or “shining” and that mistakenly used the Hebrew word for “horns,” instead. Fun Fact: This “Moses” sculpture was originally intended to be installed as an impressive large form that was supposed to loom above spectators on an upper level of the original Tomb’s design. Instead, after many years, the “Moses” was finally installed at ground level in the center of the smaller Tomb’s façade. 10 14. Tomb of Giuliano de Medici, 1519–1534, New Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence, Italy Tomb of Lorenzo de Medici, 1519–1534, New Sacristy, San Lorenzo, Florence, Italy When Giuliano de Medici [the Duke of Nemours by marriage] died in 1516 and Lorenzo de Medici [the Duke of Urbino] died in 1519, the Medici family called upon Michelangelo to design a fitting family Tomb in the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo Church in Florence. After several years and with modifications, two single tomb facades on opposite walls of the New Sacristy were installed. Each tomb memorialized the former greatness of the Medici family, now ended by the death of these last Medici men. Michelangelo depicted both of the Dukes as Roman Generals in seated positions. Neither statue was an exact portrait and when someone pointed this out, Michelangelo is supposed to have said, “a thousand years from now, nobody will know what they looked like.” The forms of Giuliano and Lorenzo represented the Active Life and the Contemplative Life, respectively. Four sculptures depicting the four times of the day were included to symbolize the ongoing cycles of time and of life—from Dawn’s beginning and new potential to the eventual fall of Night and the inevitability of death and eternity. The Active figure of Giuliano holds a baton indicating his status as a Captain-General of the papal army; he is accompanied by the figures of Night and Day. The Contemplative Lorenzo wears a Roman helmet and sits lost in thought as he holds a money bag; the figures of Dusk and Dawn recline below Lorenzo’s seated figure. Vasari wrote: “Michelangelo’s ideas for the tombs of Duke Giuliano and Duke Lorenzo de’ Medici caused even more astonished admiration. For here he decided that Earth alone did not suffice to give them an honorable burial worthy of their greatness but that they should be accompanied by all parts of the world; and he decided that their sepulchers should have around and above them four statues. So to one tomb he gave Night and Day, and to the other Dawn and Dusk; and these statues are so beautifully formed, their attitudes so lovely, and their muscles treated so skillfully, that if the art of sculpture were lost they would serve to restore to it its original luster.” 11 15. Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican, Rome In 1506, Pope Julius II initiated the reconstruction of the ancient St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Over the course of its reconstruction, a succession of prominent men were employed as the Pope’s Chief Architect. In 1546, Michelangelo took over as Chief Architect and he worked on St. Peter’s without pay for nearly 18 years, until his death in 1564. Without him, St. Peter’s would not be the incredible space it is today. Michelangelo decided to have some areas demolished and reconstructed, he redesigned the shape and structure of the Dome, he simplified the Basilica’s floor plan, and he gave the architectural features of the exterior a new rhythm and monumentality that all previous designs had lacked. Michelangelo’s design for the Dome of St. Peter’s Basilica was an elongated hemisphere rather than a typically rounded hemisphere, like that of the Pantheon. The elongation created a more pleasing and imposing exterior view and the revised Dome’s ribbed design added greater strength while the windows around the drum wall allowed more light to enter the interior. Michelangelo did not live to see St. Peter’s finished. Giacomo della Porta assumed the position of Chief Architect after Michelangelo’s death, and it was he who finally completed the project in 1590 with minimal changes to Michelangelo’s design. The exterior of the Dome reflects a symmetrical balance with evenly spaced windows that alternate with double columns around the drum wall, the vertical portion that supports the curved dome portion above. The evenly spaced vertical ribs form the dome’s imposing shape as they converge at the base of the cupola at the top. Unity is achieved by Michelangelo’s design with its organized, rhythmic, and repeated architectural details such as the columns, windows, and ribs. 12