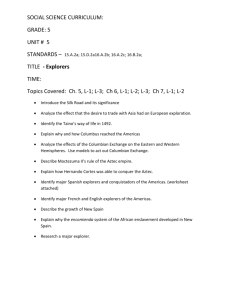

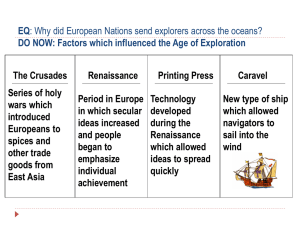

Early Encounters: Native Americans and Explorers

advertisement