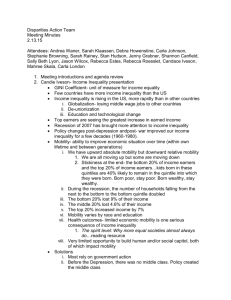

Rough draft/outline of paper for Harvard April 2010

advertisement