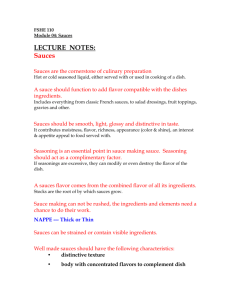

Sauces

advertisement

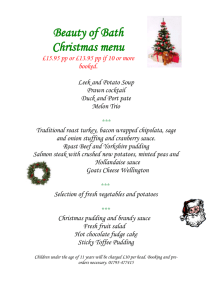

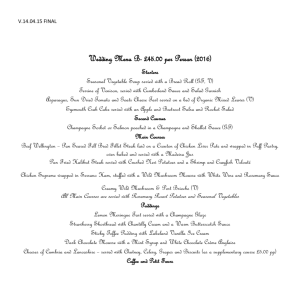

Getting started 38 Sauces Sauces 21 The main purpose of adding a sauce to a food is to add moistness, flavor, richness, to enhance the food’s appearance, and to give it appetite appeal. To make the perfect sauce is the greatest test of any chef and the ability to pair a sauce with a food shows great understanding of technique and skill. There are two categories of sauce—classic and modern. Classic sauce method Modern sauce method The “classic” sauce method involves three components—the liquid, or body, of the sauce, the thickening agent, and the addition of seasoning and flavoring ingredients. Most of the classic sauces are built on one of five liquids. These are known as the “mother” sauces (see the box below). The modern sauce method relies less on thickening agents and more on fresher, lighter flavors and ingredients. Today many chefs have also been influenced by cuisines from around the globe, such as Latin American and Asian cuisine. Because of the development of, and experimentation with, new sauces it is often difficult to classify and define them exactly. The main modern sauces are: salsa, relish, chutney, floured oil, and purée, plus a whole range of Asian sauces. Salsa is the Spanish and Italian word for sauce, but the Mexican “salsa” is made of chopped tomatoes, onions, chilies, and herbs. In most English-speaking countries the word “salsa” refers to a mixture of raw or cooked, chopped vegetables, herbs, and occasionally, fruits. Relishes are made either using raw or pickled vegetables. Chutney originated in India and is a cooked fruit and vegetable condiment that is sweet, spicy, and tangy. Floured oils make a light and interesting sauce that could be used instead of salad dressings to drizzle around the plate (see picture left.) Nearly any vegetable can be turned into a purée, sometimes called a “coulis.” Vietnamese, Indian, and Japanese sauces have recently entered the Western chef’s repertoire—it would take years of study to know them all. They are beyond the scope of an introductory cooking course . Mother sauces The five mother sauces can be turned into smaller, or derivative, sauces. For example, take hollandaise (awl-lawn-daze), add chopped tarragon and chervil and you have Béarnaise (bare-nez) sauce, then add tomato and you have Choron sauce. The liquid • Milk—béchamel (beh-sha-mel) • White stock (chicken, veal, or fish)—velouté (ve-loo-tay) sauces • Brown stock—brown sauce, or espagnol • Tomato with stock—tomato sauce • Clarified butter—hollandaise The thickening agents • Roux (roo) is a cooked mixture of equal quantities of fat and flour by weight. There are three different stages of cooking a roux: white, blond, and brown. • Starches such as flour, arrowroot, corn flour, or potato starch. • Vegetable purées. • Egg yolk and cream liaison. Eggs can thicken a liquid due to the protein in the egg coagulating with heat. The liaison enriches the sauce at the same time as thickening it. • Reduction. Although not strictly an agent, the process of simmering a sauce reduces the liquid through evaporation and therefore thickens the sauce at the same time as concentrating the flavor. The seasonings • Salt is the most important, followed by lemon juice. These two emphasize the flavor that is already there. • Cayenne and white pepper. • Madeira and sherry. • Fresh and dried herbs. Ingredients in mother sauces Liquid + Thickening agent = Mother sauce Milk + white roux = béchamel White stock (veal, chicken) + white or blond roux = velouté Brown stock + brown roux = brown sauce Tomato + stock + optional roux = tomato sauce Butter + egg yolks = hollandaise 22 Workout: Research mother sauces The next time you go out to eat, study the menu and see how many sauces fit into the classic (the five mother sauces) or modern (using light, fresh ingredients) categories. If the restaurant permits, collect menus from different venues. If you can’t take the menu away, carry a notebook and make notes about the various sauces. This will give you some great ideas to try out at home. Menus are also a great source of information when it comes to pairing ingredients—especially matching sauces with meats, fish, pastas, or vegetables. Go on the Web and check out a few of the many culinary sites available—Wikipedia has great culinary sections. Type in “mother sauces” and then see how many variant sauces you can make from one mother sauce. You’ll be surprised at the range of sauces available at your fingertips! 23 Workout: Collecting menus Workout: Make pesto Make your own pesto Recipe • 4 oz (125 g) basil leaves • 4 oz (125 g) toasted pine nuts • 2 garlic cloves, peeled • 1⁄2 tsp salt • 4–8 fl oz (120—240 ml) olive oil • 4 oz (125 g) Parmesan Put the basil, pine nuts, garlic, and salt in a food processor or pestle and mortar. Grind them together and slowly add the oil, until you have thick paste. Taste and adjust seasoning, stir in the Parmesan. 25 24 Workout: Pesto serving suggestions Add extra oil to the pesto, put it in a plastic squeeze bottle and drizzle over grilled meats or fish. Practice a zigzag or complex artistic design on or around the plate to give a rich color and dramatic effect to the presentation of your dish. Alternatively, using a spoon, lightly coat the finished dish or place a pool of sauce. dragging the spoon through it to add visual appeal. Alternatively spoon the sauce under the meat rather than on top. This allows the meat’s crust to stay crisp while also offering a contrasting circular shape beneath. Workout: Make your own maître d’hôtel butter You can roll or pipe the butter and serve it with fried/grilled meats or fish. Recipe • 1⁄2 lb (225 g) butter • 1 oz (30 g) chopped parsley • Squeeze of lemon juice 1 Stir chopped parsley and grated lemon zest into the butter, season with salt and pepper, and stir. 2 Spoon the mixture on to a sheet of waxed paper, creating a log shape. Roll the paper around the butter to create a sausage shape. 3 Compact the butter by rolling and pushing in the ends. Twist the ends firmly and tuck them under. Refrigerate for four hours. 4 To serve the butter, carefully unwrap the roll and slice it into disks, using a sharp knife. 39