strategic management of human capital in public education

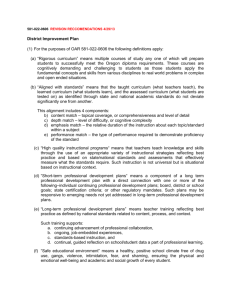

advertisement