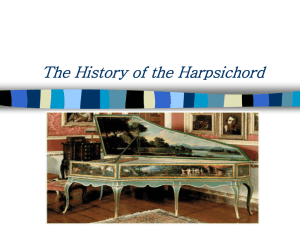

THE HARPSICHORD

advertisement

THE HARPSICHORD by PHILIP WHARTON A brief outline to accompany the Lecture Recital THE ‘ENGLISH’ HARPSICHORD or “What did the Europeans ever do for us ?” at St. Peter’s Church, Cranbourne on Sunday, 25th October 2015 1. Mediæval and Renaissance Art showing Dulcimers plucked manually with quills Detail from The Fountain of Life : Jan van Eyck (c 1395–c 1441) Mediæval Illumination (detail) Detail from "The Rutland Psalter" (c 1260) Illumination detail from The Book of Hours of Leonor de la Vega (early 15th Century) subsequently owned by the Spanish Ambassador to Flanders (c 1498) A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE HARPSICHORD Nomenclature : Italian : French : German : “Clavicembalo” / “Cembalo” “Clavecin” “Cembalo” / “Kielflugel” Early references : 1397 A jurist in Padua wrote that one HERMANN POLL claimed to have invented a CLAVICEMBALUM (a small, primitive, 1-manual Harpsichord) 1425 An Altar-piece sculpture in MINDEN, N.W. Germany, clearly depicts just such an instrument. The Harpsichord’s progenitor was probably the mediæval Psaltery or Dulcimer - which had a choir of strings stretched between bridges over a soundboard and plucked manually with quills. Eventually, someone had the idea of attaching a Keyboard (originally associated with the organ) to operate a separate piece of quill (held in a wooden ’Jack’) for each string. The Harpsichord developed and enlarged over the next 4 centuries. It remained in active use, with music specifically written for it, up to, and throughout 18th. Century, but had fallen into disuse by 1810, as its place was increasingly taken by the FORTEPIANO. The harpsichord is not only a solo instrument, for which a vast repertoire of music was written by composers in all the countries of Western and Central Europe, but was an essential constituent of chamber ensembles and orchestras as well as the almost ubiquitous accompanimental intrument for solo instruments, songs and recitative in operas and oratorios. These uses continued long after its solo function had been usurped by the Fortepiano, [fore-runner of the modern Piano]. Although no one person can definitely be credited with its invention the fortepiano was developed during J.S. Bach’s lifetime, first by CHRISTOFORI of Florence in the 1690’s, and then improved by Bach’s friend, the organ-builder SILBERMANN in the 1730’s. Bach is known to have approved of this new invention. Frederick the Great (who employed Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emanuel) was a genuine enthusiast. The first public Piano recital in England was given by another of Bach’s sons, Johann Christian, in 1768. detail from a carved wooden Altar - Piece (1425) originally in Minden Cathedral, Saxony, showing angels playing early examples of (L to R) Dulcimer, Clavicembalom and Clavichord Drawing by Henri Arnaut de Zwolle (c. 1440) showing the construction of a Clavicytherium [or Clavicembalum] Clavicytherium : German [ ? Ulm ] : 1470 [Royal College of Music Museum] Italian Single-Manual Harpsichord : Giovanni Buffo [Venice] : 1574 [in typical Italian style : a light, delicate instrument in a strong outer case] WHAT IS A HARPSICHORD ? The Harpsichord is a keyboard instrument with strings of brass or iron are stretched over a large soundboard and made to sound by being plucked. The plucking action of each note is brought about by a plectrum made from a piece of quill* from a bird’s feather (or, less commonly, soft leather) mounted in a wooden “tongue” supported in a “jack” which is propelled past the string by the back of the key-lever. On the way up, the jack plucks the string, but on the downwards return, the tongue pivots to allow the plectrum to pass the string silently. In its most developed form the harpsichord has two or more strings to each note, and may have two keyboards [“manuals”]. If there are two sets [usually called “choirs”] of strings, they will both sound at unison pitch [referred to as 8foot - an analogy with organ stops], but are plucked at different points so as to give a contrast in tone-colour. If there is a third string per note, then it will sound an octave higher [“4 foot” ] to give the sound added brilliance. There may also be an additional row of jacks to one or both of the 8’ choirs, so as to further increase the variety of tone colours available to the player, plus a “buff” stop which damped the strings of the other 8’. Some instruments (especially in Germany) had a 16-foot stop as well as the usual 2 x 8’, 1 x 4’, which added a very deep and rich timbre. In some instruments this can tend to rather ‘muddy’ the sound and reduce the clarity of the musical lines, but Bach specified such an instrument for his own use. Harpsichords cannot respond in loudness to the force or speed of the fingers, and therefore rely on the player’s ability to nuance phrasing and touch for their expression, helped, in the larger instruments, by the possibility of varying the sound by the use of ‘stops’ [as on an organ] or pedals to change which jacks and strings are in use on each keyboard [the ‘registration’]. * Modern instruments, even ‘historical’ copies, usually use synthetic substitutes such as ‘Delrin’ or ‘Celcon’ which are much more reliable and durable. 3. How a Harpsichord works Harpsichord Action (side view) Detail of a Jack Plucking Action of a Jack DEVELOPMENT of the HARPSICHORD Most of the earliest instruments were made in Italy : over 50% of all those known came from Venice, which seems to have been the cradle of a rapidly growing Harpsichord industry from the mid 15th. century. Italian instruments soon adopted a “house style” comprising a single-manual, 2 x 8’ registers of bright tone, a very light case housed within a protective “outer” which was heavy and ornate. Variety of design and concept soon took hold in other parts of Europe, however : for example, an upright harpsichord, known as a CLAVICYTHERIUM was developed (either in Germany or the Netherlands) and an example [probably from Ulm] dated c.1470 still exists [Royal College of Music Museum ]. This instrument is very similar to that described in the Henri Arnaut de Zwolle drawing of about 30 years earlier. The pinnacle of the art of the Luthier (harpsichord - maker) is generally associated with the four generations of the RUCKERS family, who worked in Antwerp from 1579 - 1706. They built a vast number of instruments, being most famous for their double-manual harpsichords. In early instruments, the two keyboards were set at different pitches [at the interval of a fourth or fifth], probably to permit easier transposition between the many different pitches used by other instruments [as depicted, for example, in Breughel’s “The Sense of Hearing” (c.1620)]. At this time, there was no universal standard pitch; indeed, Church music, Chamber music, Orchestras and Opera of the period all had their own different tuning systems. Meanwhile, the French, (as usual ! ) had been developing a different style. Their harpsichords were usually double-manual instruments with 2 x 8’ registers [often also a 4’ stop] and a method of coupling the manuals together [or sharing a “dog-leg” register] to give increased flexibility and subtlety. Early French instruments had been quite plain, delicate and light but from the late 1600s, the influence of the great Ruckers instruments led to harpsichords becoming larger, more ornate and more resonant in tone [e.g. the famous instruments by Taskin]. So great was the reputation of the old Ruckers instruments that many were re-built and enlarged so as to accommodate the wider range and sonorous bass required by the French repertoire. This rebuilding and enlargement was termed “Grande Revallement”. Many of these instruments were richly decorated and even the soundboards were painted (usually in egg tempora) . 2-Manual Harpsichords how the 2 keyboards can be ‘coupled’ The ‘Shove’ coupler (one of the keyboards is made to slide to engage or disengage the coupling) Another system : The ‘Dogleg’ (register A is shared between both keyboards) Two French Harpsichords in the Russell Collection, Edinburgh Baillon : 1755 Jean Goermans / Pascal Taskin : 1764 / 1783-4 Soundboards were often richly decorated (usually using egg tempora) This art is still practised today. DEVELOPMENT OF THE HARPSICHORD [cont.] In England, most of the instruments built before 1700 were of a single-manual, 2 x 8’ type, much influenced initially by the Italian school. Queen Elizabeth I. had a particularly fine, highly ornate virginals (q.v.) of Italian manufacture. At this time, most English makers seemed to have concentrated on virginals. After 1700, the English harpsichord developed rapidly, largely due to the influence of an Antwerp-trained maker, TABEL, who emigrated from Holland to England in 1700. It can be no coincidence that the two greatest harpsichord builders in this country, SHUDI and KIRCKMAN, were both apprenticed to Tabel. [Shudi’s son later went on to join Broadwood in a partnership which produced the best pianos of the early 19th. century, including one reputed to be Beethoven’s favourite! ] Most instruments were now of 2 manual form with increasing numbers of stops and special mechanisms to allow changes of registration whilst playing. Some were even fitted with a “Venetian Swell” : louvres in the lid [c.f. “Venetian” blinds! ] to allow some crescendo and diminuendo. Kirckman made his last harpsichord in 1809, by which time, the instrument was considered obsolete. Harpsichords were rarely used except for occasional “period” performances, (e.g. an “historical” recital by the virtuoso pianist Moscheles in 1837) and it was not until the late 1880’s when Arnold Dolmetsch took an interest, bought and restored an old Kirckman “double” and, at the instigation of William Morris, built a harpsichord for his “Arts and Crafts” exhibition. [- used for a performance of Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” at Covent Garden in 1897] The instruments used this evening both have 2 manuals with 3 sets of strings [2 x 8’, 1 x 4’ ]. One is a “5-row” harpsichord, built by Michael Thomas in 1968 and based on the style of English instruments of the late 18th century. It is tuned to A=415 (lower than modern concert pitch) and in an unequal temperament (6th-comma mean-tone). The other, by Goble (1973), though not an attempt at an ‘authentic’ historical copy, is nearer to the Franco-Flemish style. It is tuned to modern pitch and equal temperament. REVIVAL Interest in “authentic” baroque performance started again in Germany and elsewhere around 1900, and there were some, mostly ill-informed, attempts to reconstruct harpsichords at that time. WANDA LANDOWSKA was the first modern Harpsichord virtuoso. In 1912 she asked the French piano and harp manufacturer, Pleyel, to build her a large concert harpsichord. Unlike historic examples or recent copies, this had a heavy iron frame, like a grand piano, massively thick strings at high tension, heavy jacks with mostly leather plectra and 7 pedals for changing the array of registers and effects. Whilst the tuning was stable, the sound was harsh, loud and unsubtle. Not for nothing did the famous conductor Sir Thomas Beecham liken it to “. . . the sound of two skeletons copulating on a corrugated iron roof ” and “. . . playing a birdcage with a toasting fork”. Several composers wrote for Landowska - with this instrument in mind. Poulenc, for example, wrote his “Concert Champetre” for harpsichord and orchestra. In live performance, only the massive tone of the Pleyel or it’s successors is capable of being heard over the accompanying band : an historically authentic instrument would not stand a chance without electronic amplification! Landowska continued to use this instrument, or others made for her [to very similar specifications], for all her concerts and recordings, right up to her death in 1959. After World War II, interest and scholarship in “authentic” instruments and performance styles increased - led, in this country, by scholar-performers including George Malcolm, Thurston Dart and David Munrow among others, and in America by Ralph Kirkpatrick. Today we are used to hearing copies of ancient instruments of all kinds in attempts to get as close as possible to the sound-world of the great composers of past ages. The art of the harpsichord maker is thriving in many parts of the world. Some of the greatest surviving instruments have been restored to playing condition, and many very fine, historically informed, new instruments are being created. Other members of the Harpsichord Family : The Virginals and Spinet both have brass or iron strings plucked by quills mounted in “jacks”, but on account of their smaller size and shorter, lighter strings, the sound is less powerful and resonant than the harpsichord. They only ever have a single keyboard [“manual” ] and a single set [“choir” ] of strings which is usually at 8’ [unison pitch]. Miniature versions of these instruments [“Spinettino” , “Octave virginals”, etc., having a single 4’ register] were also made. The Virginals were much favoured and played (very well, apparently) by Queen Elizabeth I . The name, however, dates from much earlier and is derived from the Latin Virgae (= rods - i.e. the ‘Jacks’ which carry the quills to pluck the strings). The strings run side to side, parallel to the keyboard. English Virginals are usually rectangular in shape (superficially similar to the much later “Square Piano”), whereas Italian instruments are polygonal. In the Spinet, the strings run at approximately 45º to the keyboard. Consequently, the spinet is usually made in an angled ‘wing’ shape which results in a much more compact instrument compared to the Harpsichord. On account of their shorter strings and smaller soundboard, the Virginals and Spinet produce a sound which is much less resonant and than that of the Harpsichord . They were, essentially, intended as domestic instruments. Other Strung Keyboard Instruments : The Clavichord is similar in shape to the virginals and also has a single set of strings parallel to keys, but instead of being plucked, they are struck by a metal “TANGENT”on the end of the key-lever. This tangent also “stops” string at the correct length, forming a temporary ’bridge’. The clavichord is capable of subtle expression, but is very quiet, so it was never a concert instrument! It is also the only string keyboard instrument capable of vibrato. Many of Bach’s more intimate and thoughtful keyboard works were probably intended for the clavichord of which he was very fond. The Tangent Harpsichord : (rare, obsolete, no surviving examples) was a hybrid of the harpsichord and clavichord. Its strings were hit by wooden tangents propelled by a primitive piano-type lever action. It is sometimes considered a possible prototype for the fortepiano. In the Geigenwerk, the strings were “bowed” by pedal-driven wheels, the key action raising the appropriate wheel to its string. The idea was to produce a sustained sound which was meant to imitate violin, cello, etc. 3. Other members of the Harpsichord Family : The Virginals and Spinet English Virginals (rectangular) : Thomas White [London] : 1642 Italian Virginals (polygonal) : Annibale Rossi [Milan] : 1555 Bentside Spinet : John Crang [London] : 1758 The three images above are reproduced courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 5. Highly decorated instruments of the Harpsichord family The “Queen Elizabeth Virginal” : Giovanni Baffo, Venice, 1594 Spinet : Annibale dei Rossi : Milan : 1577 Octave Spinet : Italian c. 1560 The three images above are reproduced courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London 4. The Clavichord Interior views of Clavichords showing the Tangents on the ends of the key - levers M USICAL I LLUSTRATIONS Johann Sebastian BACH (1685 - 1750) Prelude No. 1 in C (‘48’ Preludes & Fugues : “The Well-Tempered Clavier”) Anonymous English pieces for Virginals : “The Short Mesure off My Lady Wynkfylds Rownde” from “The Mulliner Book” (mid 16th Century) “A Toy” William BYRD “Alman” and from “The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book” (c. 1616) (c.1542 - 1623) Pavanne [“The Earl of Salisbury”] & Galliard Jan Pietersoon SWEELINCK (1562 - 1621) Variations on “Est - ce Mars” Daniel PURCELL (c.1660 - 1717) Suite in D minor Jeremiah CLARKE (c.1673 - 1707) “The Prince of Denmark’s March” François COUPERIN (1668 – 1733) “Les Ondes” [“Pièces de clavecin” : 1er livre; 5me Ordre] Louis-Claude DAQUIN (1694 – 1772) “Musette” & “Tambourin” [Premiére Suite] “La Guitarre” [Première Suite] “Le Coucou” [Troisième Suite] Pietro Domenico PARADIES (1707 - 1791) Sonata VI in A Thomas ARNE (1710 – 1778) Sonata III in G Johann Sebastian BACH (1685 - 1750) ‘English’ Suite No.2 in A minor (excerpts)