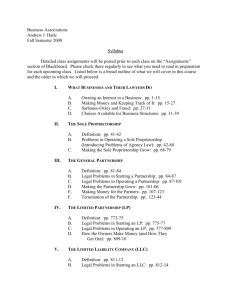

Avoiding a Limited Future For the DE Facto LLC and LLC By Estoppel

advertisement