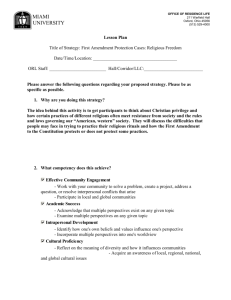

the third amendment in the twenty-first century

advertisement