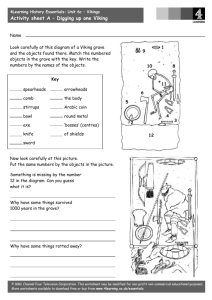

VIKING AGE SITES IN NORTHERN EUROPE

advertisement