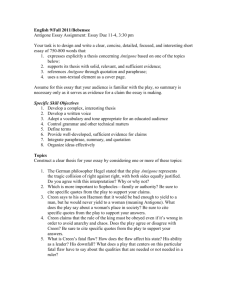

Antigone - SFP Home

advertisement