Term Length and The Effort of Politicians

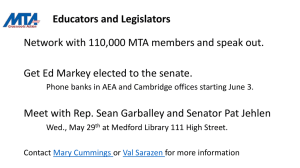

advertisement