Reconciling the Two Models of the Interest Rate

advertisement

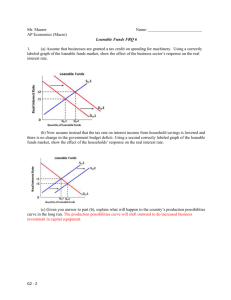

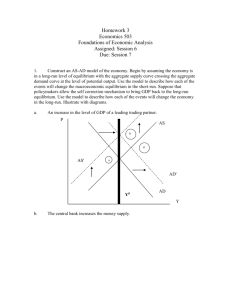

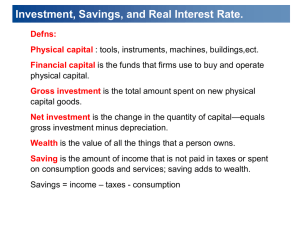

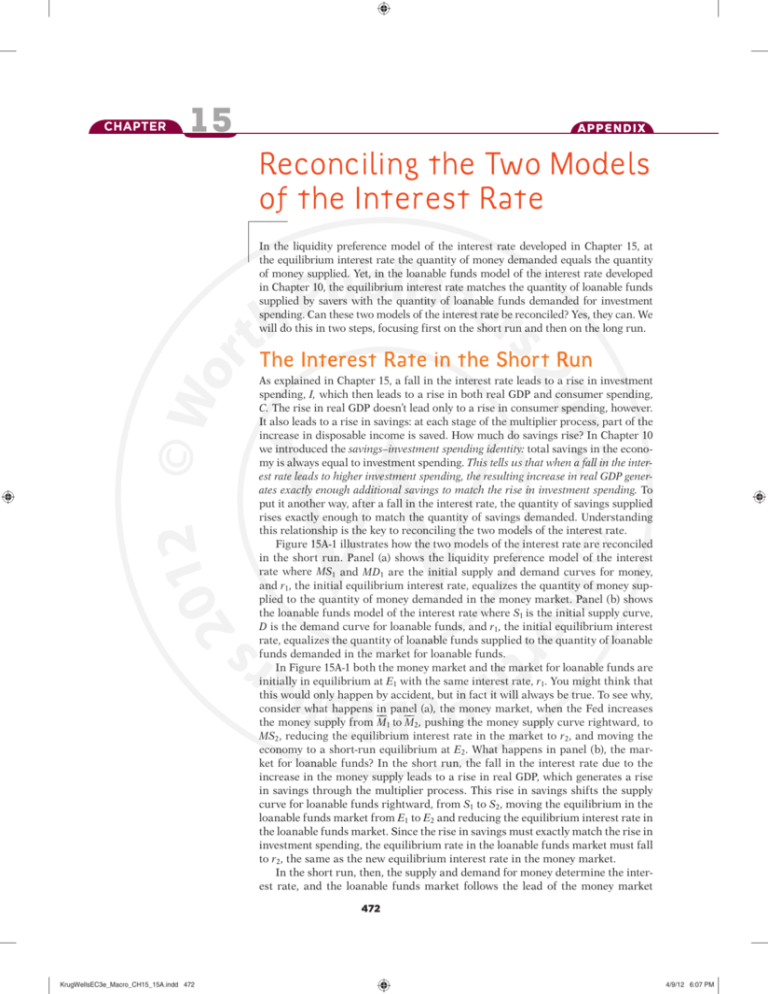

CHAPTER 15 APPENDIX Reconciling the Two Models of the Interest Rate In the liquidity preference model of the interest rate developed in Chapter 15, at the equilibrium interest rate the quantity of money demanded equals the quantity of money supplied. Yet, in the loanable funds model of the interest rate developed in Chapter 10, the equilibrium interest rate matches the quantity of loanable funds supplied by savers with the quantity of loanable funds demanded for investment spending. Can these two models of the interest rate be reconciled? Yes, they can. We will do this in two steps, focusing first on the short run and then on the long run. The Interest Rate in the Short Run As explained in Chapter 15, a fall in the interest rate leads to a rise in investment spending, I, which then leads to a rise in both real GDP and consumer spending, C. The rise in real GDP doesn’t lead only to a rise in consumer spending, however. It also leads to a rise in savings: at each stage of the multiplier process, part of the increase in disposable income is saved. How much do savings rise? In Chapter 10 we introduced the savings–investment spending identity: total savings in the economy is always equal to investment spending. This tells us that when a fall in the interest rate leads to higher investment spending, the resulting increase in real GDP generates exactly enough additional savings to match the rise in investment spending. To put it another way, after a fall in the interest rate, the quantity of savings supplied rises exactly enough to match the quantity of savings demanded. Understanding this relationship is the key to reconciling the two models of the interest rate. Figure 15A-1 illustrates how the two models of the interest rate are reconciled in the short run. Panel (a) shows the liquidity preference model of the interest rate where MS1 and MD1 are the initial supply and demand curves for money, and r1, the initial equilibrium interest rate, equalizes the quantity of money supplied to the quantity of money demanded in the money market. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds model of the interest rate where S1 is the initial supply curve, D is the demand curve for loanable funds, and r1, the initial equilibrium interest rate, equalizes the quantity of loanable funds supplied to the quantity of loanable funds demanded in the market for loanable funds. In Figure 15A-1 both the money market and the market for loanable funds are initially in equilibrium at E1 with the same interest rate, r1. You might think that this would only happen by accident, but in fact it will always be true. To see why, consider what happens in panel (a), the money market, when the Fed increases ᎐ to ᎐M ᎐ , pushing the money supply curve rightward, to the money supply from ᎐ M 1 2 MS2, reducing the equilibrium interest rate in the market to r2, and moving the economy to a short-run equilibrium at E2. What happens in panel (b), the market for loanable funds? In the short run, the fall in the interest rate due to the increase in the money supply leads to a rise in real GDP, which generates a rise in savings through the multiplier process. This rise in savings shifts the supply curve for loanable funds rightward, from S1 to S2, moving the equilibrium in the loanable funds market from E1 to E2 and reducing the equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market. Since the rise in savings must exactly match the rise in investment spending, the equilibrium rate in the loanable funds market must fall to r2, the same as the new equilibrium interest rate in the money market. In the short run, then, the supply and demand for money determine the interest rate, and the loanable funds market follows the lead of the money market 472 KrugWellsEC3e_Macro_CH15_15A.indd 472 4/9/12 6:07 PM CHAPTER 15 FIGURE A P P E N D I X : R E C O N C I L I N G T H E T W O M O D E L S O F T H E I N T E R E S T R AT E 473 15A-1 The Short-Run Determination of the Interest Rate (a) The Liquidity Preference Model of the Interest Rate Interest rate, r MS1 r1 MS2 In the short run, an increase in the money supply reduces the interest rate . . . S1 S2 r1 E1 E2 r2 (b) The Loanable Funds Model of the Interest Rate Interest rate, r E1 E2 r2 D MD1 M1 M2 . . . which leads to a short-run increase in real GDP and an increase in the supply of loanable funds. Quantity of money Panel (a) shows the liquidity preference model of the interest rate: the equilibrium interest rate matches the money supply to the quantity of money demanded. In the short run, the interest rate is determined in the money market, where an increase in the money supply, from M1 to M2, pushes the equilibrium interest rate down, from r1 to r 2. Panel (b) shows the loanable funds model of the interest rate. The fall in the Q1 Q2 Quantity of loanable funds interest rate in the money market leads, through the multiplier effect, to an increase in real GDP and savings; to a rightward shift of the supply curve of loanable funds, from S1 to S2; and to a fall in the interest rate, from r1 to r 2. As a result, the new equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market matches the new equilibrium interest rate in the money market at r 2. until the equilibrium interest rate in the loanable funds market is the same as the equilibrium interest rate in the money market. Notice our use of the phrase “in the short run.” Changes in aggregate demand affect aggregate output only in the short run. In the long run, aggregate output is equal to potential output. So our story about how a fall in the interest rate leads to a rise in aggregate output, which leads to a rise in savings, applies only to the short run. In the long run, as we’ll see next, the determination of the interest rate is quite different, because the roles of the two markets are reversed. In the long run, the loanable funds market determines the equilibrium interest rate, and it is the market for money that follows the lead of the loanable funds market. The Interest Rate in the Long Run In the short run an increase in the money supply leads to a fall in the interest rate, and a decrease in the money supply leads to a rise in the interest rate. In the long run, however, changes in the money supply don’t affect the interest rate. Figure 15A-2 shows why. As in Figure 15A-1, panel (a) shows the liquidity preference model of the interest rate and panel (b) shows the supply and demand for loanable funds. We assume that in both panels the economy is initially at E1, in long-run macroeconomic equilibrium at potential output with the money supply ᎐ . The demand curve for loanable funds is D, and the initial supply curve equal to ᎐ M 1 for loanable funds is S1. The initial equilibrium interest rate in both markets is r1. ᎐ to ᎐M᎐ . As in Figure 15A-1, this Now suppose the money supply rises from ᎐ M 1 2 initially reduces the interest rate to r 2. According to the neutrality of money, in the long run the aggregate price level rises by the same proportion as the increase in the money supply. And we also know that a rise in the aggregate price level increases money demand by the same proportion. So in the long run the money demand curve shifts out to MD2 as money demand responds to KrugWellsEC3e_Macro_CH15_15A.indd 473 4/9/12 6:07 PM 474 PA RT 6 FIGURE S TA B I L I Z AT I O N P O L I C Y 15A-2 The Long-Run Determination of the Interest Rate (a) The Liquidity Preference Model of the Interest Rate Interest rate, r 1. In the long run, the rise in the price level shifts the money demand curve to the right, . . . MS1 r1 S1 MS2 E3 E1 S2 2. . . . which raises the interest rate back to its original level . . . E2 r2 (b) The Loanable Funds Model of the Interest Rate Interest rate, r r1 E1 3. . . . reducing real GDP and the supply of loanable funds until aggregate output equals potential output. E2 r2 MD2 MD1 M1 M2 D Quantity of money Panel (a) shows the liquidity preference model long-run — adjustment to an increase in the money supply from M1 to — M2; panel (b) shows the corresponding long-run adjustment in the loanable funds market. Both panels start from E1, a long-run macroeconomic equilibrium at potential output and with interest rate r1. As we discussed in Figure 15A-1, the increase in the money supply reduces the interest rate from r1 to r2, increases real GDP, and increases savings in the short run. This is shown in panel (a) and panel (b) as the movement from E1 to E2. In the long run, however, the Q1 Q2 Quantity of loanable funds increase in the money supply raises wages and other nominal prices. This shifts the money demand curve in panel (a) from MD1 to MD2, leading to an increase in the interest rate from r2 to r1 as the economy moves from E2 to E3. The rise in the interest rate causes a fall in real GDP and a fall in savings, shifting the loanable funds supply curve back to S1 from S2 and moving the loanable funds market from E2 back to E1. In the long run, the equilibrium interest rate is determined by matching the supply and demand for loanable funds that arises when real GDP equals potential output. higher prices, and moving the equilibrium interest rate rises back to its original level, r1. Panel (b) of Figure 15A-2 shows what happens in the market for loanable funds. As before, an increase in the money supply leads to a short-run rise in real GDP, and this shifts the supply of loanable funds rightward from S1 to S2. In the long run, however, real GDP falls back to its original level as wages and other nominal prices rise. As a result, the supply of loanable funds, S, which initially shifted from S1 to S2, shifts back to S1. In the long run, then, changes in the money supply do not affect the interest rate. So what determines the interest rate in the long run—r1 in Figure 15A-2? The answer is the supply and demand for loanable funds. More specifically, in the long run the equilibrium interest rate matches the supply and demand for loanable funds that arise at potential output. PROBLEMS 1. Using a figure similar to Figure 15A-1, explain how the money market and the loanable funds market react to a reduction in the money supply in the short run. 2. Contrast the short-run effects of an increase in the money supply on the interest rate to the long-run effects of an increase in the money supply on the interest rate. Which market determines the interest rate in the short run? Which market does so in the long run? What are the implications of your answers for the effectiveness of monetary policy in influencing real GDP in the short run and the long run? www.worthpublishers.com/krugmanwells KrugWellsEC3e_Macro_CH15_15A.indd 474 4/9/12 6:07 PM