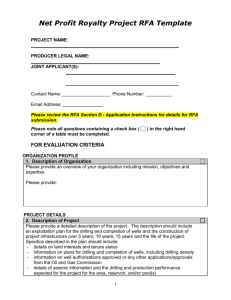

Louisiana Mineral Law Legal Update

advertisement

LOUISIANA MINERAL LAW LEGAL UPDATE Presentation and Materials by JASMINE B. BERTRAND and JEREMY B. SHEALY Materials also by RANDALL C. SONGY and KEVIN M. BLANCHARD 1200 Camellia Boulevard, Suite 300 (70508) P.O. Box 3507 Lafayette, LA 70502 Telephone: (337) 237-2660 Facsimile: (337) 266-1232 E-Mail: mailto:songyr@onebane.com bertrandj@onebane.com shealyj@onebane.com www.onebane.com 3255504.1 Louisiana Mineral Law Legal Update PART 1: CASE LAW UPDATE A. MINERAL LEASE CASES 1. Notice Provided to Lessee’s Sister Subsidiary Company Might Constitute Notice to the Lessee: Estess v. Placid Oil Co., CIV.A. 12-0052, 2012 WL 1222729 (W.D. La. Apr. 10, 2012) In Estess, the Plaintiffs brought suit against Placid Oil Company (“Placid”) alleging that Placid failed to develop a 1972 mineral lease as a reasonably prudent administrator, failed to seek a revision of the true drainage area for the unit well, and failed to pay royalties due to the Plaintiff. Placid brought a motion to dismiss claiming prematurity of the claims, as under the Louisiana Mineral Code, all claims of the Plaintiff required written notice and reasonable time to respond and the Plaintiffs had failed to give such notice. The Plaintiffs had sent notice to Oxy USA, Inc. (“Oxy”) giving notice of their demands regarding drainage and failure to develop the property. Oxy is a separate subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum Corporation (“Occidental”), which was the “eventual parent company” of both Oxy and Placid. A series of letters between Plaintiffs and managing counsel for Oxy (who was also counsel for Placid) followed. Thus the issue for determination was whether notice was provided to Placid in compliance with the notice provisions under the Louisiana Mineral Code in order for the Plaintiffs to bring their claims. The Western District cited La. R.S. 31:136, which requires a mineral lessor to give his lessee written notice in order to make a claim against the lessee for claims of drainage or failure to develop and operate the property as a prudent operator, and La. R.S. 31:137, which requires a mineral lessor to give his lessee written notice in order to make a claim against the lessee for failure to make timely or proper payment of royalties. The Court noted that both statutes require the lessor to not only give notice, but require the lessor to allow the lessee reasonable time to cure the alleged breach, prior to making a judicial demand. The Court also noted that the 1972 Lease included a provision which stated that “in the event Lessor considers that operations are not being conducted in compliance with this contract, Lessee shall be notified in writing of the facts relied upon as constituting a breach hereof and Lessee shall have sixty (60) days after receipt of such notice to comply with the obligations imposed by virtue of this instrument.” After examining the statutes and the lease language, the Court applied the facts to determine that Placid had been placed on notice of the Plaintiffs’ claims. In this instance, written notice from the Plaintiff was directed at Oxy, not Placid, which was not the lessee of record. However, the managing counsel for Oxy was the same person as the managing counsel for Placid. When counsel replied to the notice that was addressed to Oxy, “he made it clear in his 3255504.1 reply correspondence that he was responding on behalf of Oxy and Placid, if for no other reason than the fact he wrote one letter on Oxy letterhead and one on Placid letterhead, while serving as managing counsel for both.” The Plaintiffs had received correspondence from managing counsel on both Oxy and Placid letterhead. In his initial correspondence, managing counsel had directed Plaintiffs to direct all correspondence to him. Thus, the Court found in favor of the Plaintiffs, finding that the written notification made to managing counsel of Placid satisfied both the Louisiana Mineral Code’s notice requirements as well as the requirements made by the parties to the lease. 2. Lessee Found to Have No Cause of Action under LUTPA against Lessors: Bogues v. Louisiana Energy Consultants, Inc., 71 So. 3d 1128 (La. App. 2 Cir. 8/10/11) In Bogues, a group of 22 lessors sued Louisiana Energy Consultants, Inc. (“LEC”), their lessee through assignment, seeking termination of the leases and damages for failure to timely pay royalties and operate the leasehold as a reasonable and prudent operator, and breach of the implied covenant of reasonable development. LEC filed a reconventional demand based on claims of unfair trade practices under the Louisiana Unfair Trade Practices Act (“LUTPA”) and of tortious interference with business, claiming lessors had “engaged in a campaign to discredit LEC” in its negotiations to farm out its interests to third parties so that they (the lessors) could negotiate more favorable terms with those third parties for development of the deep rights to the lands covered by the leases. LEC claimed this made the lessors “potential business competitors.” The Court noted that in order to recover under LUTPA, a plaintiff must prove fraud, misrepresentation, deception or other unethical conduct on the part of the defendant, but that LUTPA does not prohibit sound business practices or the exercise of business judgment. In finding that the facts of the case did not lead to a cause of action under LUTPA, the Court stated that although the lessors “were unhappy with the leasing arrangement” and with LEC’s operations thereunder, there was nothing unethical about the meetings the lessors had amongst themselves to discuss same. Similarly, the Court found that LEC did not have a cause of action for tortious interference with LEC’s business, as LEC could not put forth evidence of any conversation between a particular lessor and any particular potential farmee with whom LEC was trying to conduct business, nor any evidence of malice on the part of the lessors. 3. Attorney’s Fees Denied in Lease Rescission Case: Adams v. JPD Energy, Inc., 87 So. 3d 161 (La. App. 2 Cir. 2/29/12) This was the second disposition in Adams v. JPD Energy, Inc., a lease rescission case brought before the Second Circuit. In the first disposition of the case, the Court held a 2008 mineral lease in the Haynesville Shale to be null and void for failure of the parties to have a meeting of the minds or mutual consent regarding the royalty percentage. The second disposition concerned whether the Adamses were entitled to recover attorney’s fees under La. R.S. 31:206 and 31:207, which allow for an award of attorney fees when a lease is extinguished or expired. JPD contended that the statutes only applied where a valid mineral lease was extinguished and that here, no valid lease was ever formed. The Second Circuit agreed with JPD. The Court stated that La. R.S. 31:206 et seq., refer to authorization to cancel extinguished mineral rights from the public record. However, rather than being 3255504.1 extinguished or expired, a lease found null is deemed never to have existed. Therefore the Court found that La. R.S. 31:206 and 31:207 did not apply and an award of attorney’s fees was inappropriate. 4. Reformation of Lease Denied: Hall Ponderosa, LLC v. Petrohawk Properties, LP, 90 So. 3d 512 (La. App. 3 Cir. 4/4/12) Hall Ponderosa executed a mineral lease with Petrohawk Properties covering its tract in Section 14 (Stella Plantation) in Red River Parish. Later, Hall brought this suit to have the lease reformed to include its lands located in Section 13 in Red River Parish, which was left out of the original agreement, allegedly, by mutual error, and seeking additional bonuses of $15,000.00 an acre based on the additional acreage. The lessor’s basic argument was that while the left-out section of property was never specifically mentioned during lease negotiations, each party intended to lease all of lessor’s property. After trial on the merits, the trial court found in favor of the lessor, ordering the lease to be amended to include the additional 144 acre tract and ordering the lessee to pay nearly two million dollars as remuneration. In reversing the trial court, the Third Circuit found the record to be devoid of any evidence of mutual error. The lessor never once mentioned owning the Section 13 property to the lease broker during negotiations. The Court noted that the lessors did not attempt to have the extra section included in the lease until nearly a year after the lease was signed. Finally, one of the lessor’s principals testified that he signed the lease without reading it, while another said that he signed the lease after seeing that it did not include a property description for the extra section. The Court held that this negligence on their part precluded them from seeking reformation. 5. Permit to Drill Well Not a Title Defect for Purposes of Top Lease Agreement: Pilkinton v. Ashley Ann Energy, L.L.C., 77 So. 3d 465, 2011 WL 5170296 (La. App. 2nd Cir. 2011) Pilkinton involved an addendum to a top lease, in which the parties agreed that the top lease was “expressly made subject” to the prior lease, that the top lease was not intended in any way to cloud or impair the rights of the parties to the prior lease, and that the top lease would come into being “only following the termination” of the prior lease, at which time the remaining bonus be paid. Another provision waived warranty, emphasizing that the lessor would not be obligated to return any bonus consideration on account of a failure of title. Upon execution, top-lessee gave to the lessors a draft for $431,000—representing one-quarter of the $20,000 per acre bonus payment—which included a provision reading “upon approval of title but not later than 20 banking days after sight.” Two weeks later—and within the 20-day provision—the original lessee secured a drilling permit for a unit well. The top-lessee viewed this as a title defect and refused to honor the draft. The top-lessee argued that the 20-day provision on the draft, read together with the addendum to the top lease agreement, set up a 20-day period within which the top lease agreement could fail to become effective because of a “title defect.” The Second Circuit held that the language of the top lease was clear and unambiguous, saying that a top lease, at its inception, exists as a “mere hope or expectancy in the extinction of existing superior leasehold rights.” Importantly, the Court noted the meaningful difference between the effects of permitting a well and those of drilling a well, on the maintenance of a lease beyond its primary term under the standard habendum clause. Here, the defendants had tried to avoid honoring the top lease agreement because the original lessee had secured a drilling permit. But the act of securing a drilling permit would not by itself maintain the lease. Because the well permit could not have a bearing on whether the original lease was extended, it 3255504.1 could not be considered a flaw in the lessor’s title. The Court noted that some other type of title flaw— like another party’s ownership of the mineral servitude burden on the land—might have triggered the 20-day provision in the top-lessee’s favor. 6. Double Damages and Attorney’s Fees Awarded where Concursus Filed After Royalty Demand Made : Oracle 1031 Exchange, LLC v. Bourque, 85 So. 3d 736 (La. App. 3 Cir. 2/8/12) In Oracle, royalty owners sent demand letters to three entities, Oracle, Delphi, and Exchange, demanding payment of unpaid royalties. Thereafter, Exchange filed a petition for concursus and Oracle deposited money into the registry. The plaintiffs then reconvened against Exchange and made third party demands against Delphi and Oracle, asking for penalties and attorney’s fees under La. R.S. 31:139. The trial court awarded the royalty owners double damages and attorney’s fees. The appellate court upheld the trial court’s decision. This damage award included Oracle and Delphi on the theory that they all constituted a single-business enterprise. Although Exchange was the only company with working interest in the assigned leases, the Court found that Oracle and Delphi had engaged in other activities, including operating the well, depositing the money in the registry of the court in the concursus proceeding, paying taxes on the oil sales, and writing the check for the only royalty payment actually made. Additionally, all three entities were headed by the same person. The Court found that penalties were appropriate, despite the defendants’ argument that their invoking a concursus proceeding should preclude same. The Court stated that the defendants’ failure to pay was “willful or without reasonable grounds,” finding little merit to the defendants’ arguments that they were unsure whether royalties were due considering the “minimal amount” of oil produced and that there were unresolved title problems with the lands covered by the leases. This was especially true where the defendants chose to file the concursus proceeding only after “being prompted to take action by the royalty owners’ letter demanding payment.” 7. Fraud Claim Upheld in Favor of Lessor: Petrohawk Properties, LP v. Chesapeake Louisiana, LP, 689 F.3d 380 (U.S. 5th Cir. 7/24/2012) Petrohawk v. Chesapeake concerns competing leases negotiated during the rush to lease the Haynesville Shale formation. In April 2008, the Stockmans executed an extension of their existing lease with Chesapeake, which was to expire on July 14, 2008, receiving a $240,000 bonus. On May 8, 2008, the Stockmans were approached by a landman on behalf of Petrohawk about leasing their property. The landman told the Stockmans that the extension was invalid because it had not been recorded. The landman did not inform the Stockmans that the extension was valid between the parties, despite it not having been recorded, and did not inform them that they could be liable to Chesapeake by signing a competing lease. On May 9, 2008, the Stockmans executed a lease with Petrohawk for a $1.45 million bonus. The landman described the lease as a “placeholder” in order for Petrohawk to win the race to the courthouse. The Petrohawk lease was recorded that same day, and the Chesapeake extension was recorded May 19, 2008. Before depositing the Petrohawk draft, the Stockmans confirmed that the extension had not been recorded. He thereafter had an attorney draft a letter revoking his consent to the Chesapeake extension and returned the bonus money. Petrohawk’s draft was due to be paid to the Stockmans on July 2, 2008, prior to the expiration date of the Chesapeake lease, and therefore Petrohawk dishonored the draft. The Stockmans spoke with a Petrohawk representative and was led to believe that either party could walk away from the May 9 lease, but 3255504.1 that if the Stockmans did so, they would not receive the $1.45 million bonus. The Stockmans were told that if they allowed a delay in payment until July 15, Petrohawk would increase the bonus. On July 15, 2008, Petrohawk executed a second lease with the Stockmans, paying them a $1.7 million bonus. After a settlement between Chesapeake and the Stockmans, the Stockmans sued Petrohawk for fraud in obtaining the first lease, Chesapeake sued Petrohawk for intentional interference with its contract, and Petrohawk sought a judgment that its lease was valid or, in the alternative, for a return of the bonus. The trial court found that Petrohawk procured the first lease by fraud and rescinded the lease and dismissed both Chesapeake and Petrohawk’s claims. In affirming the trial court’s decision, the Court first addressed the Stockmans’ fraud claim. First, the Court found that the landman’s misrepresentation to the Stockmans regarding the invalidity of the lease extension because of Chesapeake’s failure to record same was made as a statement of fact so that the Stockmans would sign the Petrohawk lease and could form the basis of a fraud claim. The Court dismissed Petrohawk’s argument that the landman’s misrepresentation of law could not give rise to a fraud claim. Second, the Court found evidence of Petrohawk’s intent to defraud the Stockmans. Petrohawk’s landman had testified that she was an experienced landman and a former paralegal very knowledgeable about Louisiana law. The Court saw this as evidence that the landman knew she was lying to the Stockmans about the validity of the Chesapeake extension. It found documentary evidence that Petrohawk “was willing to say or do anything to” obtain the Stockman lease. The Court also found intent to defraud through the landman’s statements to Mr. Stockman, when he voiced some legal concerns related to the Chesapeake extension, that he should not worry, because “Petrohawk ha[d] an office full of lawyers.” Third, the Court found that the district court’s determination that the Stockmans relied upon the landman’s misrepresentations was not clearly erroneous. Finally, the Court rejected Petrohawk’s argument that the Stockmans could have easily ascertained the truth, stating that in order to do so, the Stockmans would have needed to consult with a knowledgeable attorney because ascertaining the truth required special skills not possessed by a mere landowner. The Court also found that the Stockman’s subsequent revocation of the first lease and acceptance of the bonus did not amount to a confirmation of the fraud because it was done without actual knowledge of the fraud. Petrohawk was not entitled to a return of the bonus because the second lease was neither an amendment to the first, nor was it a novation. Chesapeake could not bring its claim against Petrohawk because Petrohawk owed no individualized duty to Chesapeake. 8. Preliminary Acts Performed in Good Faith Constitute Commencement of Drilling Operations: Cason v. Chesapeake Operating, Inc., 92 So. 3d 436 (La. App. 2 Cir. 4/11/12). The Cason case concerns whether putting surveyors on the ground, staking the well, cutting of trees and stacking of lumber constituted the commencement of operations for drilling in compliance with the terms of a mineral lease with a primary term ending May 31, 2010, where a drilling permit was not obtained until after the end of the primary term. The Court noted that despite the lessor’s insistence that the preparatory work was “sluggish,” the evidence showed that Chesapeake spent $8.5 million bringing in the eventually productive well. It discussed the jurisprudence holding that the general rule is that actual drilling is unnecessary but that preliminary acts performed in good faith may constitute commencement of operations. While the preparatory work may have taken longer than normal, the terrain in the area made work difficult. The Court also found that the lessor was properly enjoined from continuing to refuse 3255504.1 right-of-way for a pipeline to be constructed from a section of land not covered by the lease because of the lease’s adjacent lands clause. B. MINERAL RIGHTS CASES 1. Unilateral Execution of Royalty Amendment Found Effective: Cecil Blount Farms, LLC v. MAP00—NET, 2012 WL 3025134, ___ So. 3d ___ (La. App. 2 Cir. 7/25/12): On November 1, 2001, the parties executed and recorded a standard printed form royalty deed with an insertion that the royalty was for a term of seven years. One month later, on December 3, 2001, the mineral owner executed and recorded an amendment to the royalty deed to define the seven year term more specifically. The amendment stated that the royalty was to be subject to “an initial period of liberative prescription of seven (7) years from the date hereof. Thereafter, in the event of a cessation of production the period of liberative prescription shall be one (1) year from the date of last production.” The mineral royalty was subject to mesne conveyances as well as a recognition and confirmation of the amendment to the royalty from the original mineral royalty owner. The recognition and confirmation, however, was executed and recorded after the original mineral royalty owner had already conveyed his interest in the royalty. In May 2009, the then-landowner/mineral owner advised the then-royalty owners that the royalty had expired and demanded the execution of a release, claiming that the 2001 amendment was invalid because of failure of consideration, the grantee did not join in the amendment, and it was not executed as an authentic act. The Court first addressed the effect of the amendment. The royalty owners argued that the original royalty deed provided for a fixed seven year term and that the amendment created a prescriptive period of seven years. The landowner/mineral owner agreed with the royalty owners’ assessment, but argued that the amendment was ineffective for the reasons stated above. The Court cited Louisiana Civil Code article 1839, requiring that immovable property be transferred by authentic act or by act under private signature, and article 1837, which requires the signatures of both parties for an act under private signature. However, the Court noted, the comments to article 1837 state that an act under private signature can still be valid even when signed by only one party, when the party who did sign asserts the validity against a non-signing party whose conduct reveals that he has availed himself of the contract. The Court pointed out that in this case, the amendment benefited the royalty owner, i.e., the party who did not sign the amendment. Although the original royalty owner had already conveyed his interest in the royalty when he executed the recognition and confirmation, the Court found that here, the original royalty owner evidenced acceptance by conveying the royalty interest one day after they had become subject to the amendment. It further noted that the royalty purchaser acquired the mineral royalty subject to the amendment, which had been recorded the previous day. 2. Contra Non Valentem Applied to Unleased Mineral Owner’s Claim: Wells v. Zadeck, 89 So. 3d 145 (La. 5/30/12) The Wells case concerns a mineral servitude created in 1949 in favor of Mr. and Mrs. Wells, burdening a one-half interest in and to 120 acres in DeSoto Parish. The owners of the other one-half interest were Mr. and Mrs. Holmes. The Wellses divorced in the 1950s, with each of them receiving an undivided one-fourth interest in and to the minerals in their community property settlement. In 1954, Mrs. Wells executed a mineral lease. The Lease was released in 1958 when the well resulted in a dry hole. In 1961, Mr. and Mrs. Holmes executed a mineral lease, the property was included in a unit, and 3255504.1 production from that unit continued through 2007. However, Mrs. Wells, who had moved away from the area after the release, never knew about the production. She died in 2002 never having received any payment due her as an unleased owner. Her son, as successor, brought suit in 2009, only after finding out about the production and lease after receiving a call from a landman interested in leasing his mineral interest. Zadeck, one of the defendants in the suit, filed an exception of prescription based on the theory that Wells’ claim was quasi contractual, governed by a ten year prescriptive period. Zadeck stated that it had ceased being the operator of the well in 1994 and that therefore the claim Wells had against Zadeck for failure to pay him as an unleased owner had prescribed. The issue in the case was whether the doctrine of contra non valentem, a doctrine that suspends the running of prescription, excused the plaintiffs from having not timely brought an action against Zadeck for failure to follow its statutory duty to make payments to the unleased mineral owner. The Louisiana Supreme Court first set forth the four instances where contra non valentem can be applied, finding the fourth, being “where the cause of action is not known or reasonably knowable by the plaintiff, even though this ignorance is not induced by the defendant”, to be at issue. After a discussion of the jurisprudence regarding application of the fourth category of the doctrine, the Louisiana Supreme Court stated that the test for a determination of whether the doctrine should apply in this case was whether Mrs. Wells’ inaction was reasonable in light of her education, intelligence, and the nature of the defendant’s conduct. The Court took note that Mrs. Wells was an unsophisticated single-mother who lived away from the area and who had never received her statutorily required payment or notice of unitization. The Court stated that Zadeck would clearly have had notice that, when it acquired only a one-half interest in the property through the Holmes’ lease, the other one-half interest was owned by another person or entity. Zadeck failure to comply with its statutory duty to pay its unleased interest owner was a factor the Court considered in assessing the reasonableness of Mrs. Wells’ conduct, in light of her intelligence and situation. The Court stated that “an unleased mineral interest owner, who was minimally educated and not living in the same parish where the subject unit well was located, should not be required to continuously search the public records, make cold calls, or investigate the possibility of a unit well not located on the property subject to the mineral servitude.” It then held that Mrs. Wells’ particular inaction was reasonable and her ignorance of the claim was not negligent, and that contra non valentem operated to suspend the running of prescription against the claim. 3. Subdivided Tract Created Mineral Servitude Which Prescribed: Horton v. Browne, 2012 WL 2478274, ___ So. 3d ___ (La. App. 2 Cir. 6/29/12). The Horton case concerns a donation inter vivos executed in 1997, wherein the mother of the plaintiffs divided a 40 acre tract of land into three tracts, giving two 18.75-acre tracts to two of her children and one 2.5-acre tract to one of her children. The donation further provided that each sibling receive an undivided one-third interest in the minerals underlying the 40 acres, thus creating a single mineral servitude burdening the tract. Through a series of transactions in 2002 and 2003, the acreage was sold to Browne, the defendant, with the plaintiffs reserving mineral rights. No wells were spud on the property until 2010. In the suit, the plaintiffs sought a declaratory judgment recognizing them as owners of the minerals. The defendant sought declaration that the plaintiffs’ servitude had prescribed 3255504.1 in 2007. The trial court determined that the donation inter vivos had created a servitude that prescribed in 2007 for non-use, and that therefore the defendant was the owner of the mineral rights. In the appeal, the plaintiffs made two basic arguments. First, the plaintiffs argued that the 1997 donation did not create a valid mineral servitude. They based this argument on La. R.S. 31:66, which provides that owners of several contiguous tracts can create a single mineral servitude, stating that in this case, there was only one owner, in the singular. The Court disagreed, however, finding that the donation of the surface rights and the donation of the mineral rights were two separate donations, albeit encapsulated in the same instrument. The plaintiffs’ second argument was based upon application of the doctrine of confusion. The plaintiffs argued that the transfer resulted in confusion of ownership of surface and mineral rights. However, in this instance, the dominant and the servient estates were never acquired in their entireties by the same individual and therefore confusion did not apply. C. OPERATIONS CASES 1. No Cause of Action against DNR where P&A of Wrong Well Saved Working Interest Owner Money: Winn v. State Dept. of Natural Resources, Office of Conservation, 2012 WL 3192767, ___ So. 3d ___ (La. App. 2 Cir. 8/8/12): In 2004, an employee of the Department of Natural Resources (“DNR”) directed an independent contractor, pursuant to the department’s Abandoned Well Program, to plug what turned out to be the wrong well. Winn, the working interest owner of the well, however, who owned two wells in the area—the other of which was supposed to have been plugged—did not notice the error until years later. Winn filed suit against DNR, the independent contractor, and the parties he had hired to oversee physical operations of the well, seeking damages for lost production and the cost of drilling a replacement well. In affirming the trial court’s grant of summary judgment in favor of DNR and the independent contractor, the Second Circuit agreed with the trial court that the well owner had failed to establish the necessary element of damages to support a negligence claim against DNR. DNR had an expert demonstrate that, because the well had been declining in production before its wrongful plugging, the plaintiff had likely saved money because of the mistake. In other words, the plaintiff would have made less money in production proceeds over the years than he would have been required to spend if he would have had to shoulder the cost of plugging the well himself. The well owner, who admitted he was not sophisticated in the oil and gas business, and had a hard time even finding his own well sites, could not produce any contradictory evidence. 2. Transportation Costs Properly Deducted as Post-Production Processing Costs: Culpepper v. EOG Resources, 92 So. 2d 1141 (La. App. 2 Cir. 5/16/12) The sole issue in Culpepper was whether or not transportation costs could be properly deducted from gross revenues when computing a lessor’s royalty payment when the contract language at issue provided that royalties were determined upon gas production “computed at the mouth of the well.” An earlier case, Merritt v. Southwestern Electric Power Co., 499 So. 2d 210 (La. App. 2 Cir. 1986) had found the language “at the mouth of the well” to mean that compression costs were deductible post- 3255504.1 production costs. The court found that, under the reasoning in Merritt, there was no market for the gas “at the mouth of the well” because it was useless and had no market value until it was transported. Because the parties had not provided otherwise by contract, the lessee properly withheld transportation costs as post-production processing costs. 3. Pipeline Company with Expropriation Authority Has Much Discretion in Selecting Site: Acadian Gas Pipeline Sys. V. Nunley, 46,648 La. App. 2 Cir. 11/2/11, 77 So. 3d 457, 458 writ denied, 2011-2680 La. 2/10/12, 80 So. 3d 487 This case concerns a natural gas pipeline Acadian was constructing from Napoleonville to Mansfield, a portion of which it sought to cross the Nunley’s 400-acre tract in DeSoto Parish. After unsuccessful negotiations with the Nunleys, Acadian filed suit, alleging that it had acquired expropriation authority through a certificate of transportation from the Department of Natural Resources to acquire property necessary for transporting and supplying the public with natural gas under Louisiana law. The trial court found in Acadian’s favor. The main issue on appeal concerned the evidence at trial presented by Acadian and testimony by Acadian’s senior project manager with respect to the route chosen for the pipeline. The Nunley’s took issue with the fact that Acadian produced no data such as designs, photographs, field notes and constructability notes with respect to the site selection process, but instead relied on the testimonial evidence of the project manager. In its discussion, the Second Circuit noted that with respect to site selection, the expropriator must act in good faith and consider factors such as costs, environmental impact, long-range area planning and safety considerations. However, the Court found that testimony alone may suffice to prove that the expropriator considered these factors. PART 2: STATUTORY UPDATE CHANGES TO “RISK FEE” STATUTE BY ACT 743 OF 2012 Act 743 of 2012 revises La. R.S. 30:5.1 to add new provisions for the creation of units for “ultra deep structures” and also revises La. R.S. 30:10 to significantly change the operation and dynamics of the “risk fee” provisions of the statute. This outline addresses the latter revisions, with an emphasis on the most notable changes, in general comparing how the “risk fee” system operates both before and after the August 1, 2012 effective date of the Act. Generally, the risk fee procedure is one in which a party desiring to drill a well to serve a unit may (a) send out a Notice of Intent to drill a well to all other working interest owners in the unit, (b) require each of those owners to commit to whether they will participate in the risk and expense of the well, and (c) collect out of the non-participant’s share of unit production, not only 100% of the non-participant’s share of the cost of drilling, testing, completing, equipping and operating the well, but also an additional “risk charge”, being a percentage (in the current statute 200%) of the costs of drilling, testing, and completing the well. The drilling party, however, may not collect the risk charge from unleased owners. 3255504.1 Which wells qualify? Under the prior version of the statute, operators had to follow this procedure for unit wells, including substitute unit wells. The statute did not expressly mention whether alternate unit wells were included. The procedure was available only if there was no cost-sharing agreement in place. Now, the revised statute specifically provides that unit wells, substitute unit wells, alternate unit wells, and cross-unit wells all may qualify for use of the procedure—although, again, only if there is not a cost-sharing agreement in place. What content is required in the Notice? Under the old statute, the Notice which must be sent by the drilling party to activate the risk fee procedure was required to include: (1) an estimate of cost of drilling, testing, completing and equipping the proposed well; (2) the proposed location; (3) the proposed objective depth; and (4) if the well had been drilled or was drilling, all non-public logs, core analysis, production and well test data. The revised statute still requires that those same items be included, but also specifies that additional information must be included in the Notice, including a current authorization for expenditure form, or AFE, that includes a “detailed” estimate of costs of drilling, testing, completing and equipping the proposed well, and an estimate of unit ownership percentage of the recipient. When must the Notice be sent? The prior statute contained no deadlines for sending the Notice. For various reasons, it was advantageous for the drilling party to send the Notice as early as possible; further, the Notice could always be reissued later if there was a need to correct omissions or erroneous names or addresses of owners. The revised statute appears to set a hard deadline for sending the Notice. The Notice is now, apparently, required prior to the actually spudding of a well if the unit is in place on the spud date. But if the unit was created during or after drilling, then the Notice is required to be sent within 60 days of “date of the order” creating the unit. If the unit is revised to include an additional tract or tracts after drilling, then the Notice is required to be sent within 60 days of “date of the order” revising the unit. It is not clear whether the statute is referring to the date the order was issued or the date the order was made effective, which is usually the hearing date, which can be 30 or more days prior to the issuance date. Because of this change, there is apparently no longer a chance for a drilling party to correct errors or omissions after these deadlines have passed. If the initial Notice is improper or late, then the drilling party may lose the ability to collect the risk charge. 3255504.1 When must participating party pay to avoid risk charge? Under the old statute, the participating party had to make payment within 60 days of receipt of “detailed invoices” in order to avoid being deemed a nonparticipating party subject to the risk charge. This likely meant that the drilling party could not require payment until 60 days after it had sent third party invoices to the participating party. Under the revised statute, the participating party is required to pay the drilling costs as per the AFE within 60 days of spud in order to avoid being deemed a nonparticipating party subject to the risk charge. Additionally, any “subsequent drilling, completion and operating expenses” have to be paid within 60 days of receipt of subsequent detailed invoices. What is the amount of the risk charge? Under the prior version of the statute, the risk charge equaled 200% of drilling, testing and completing costs for unit and substitute unit wells. Alternate and cross-unit wells were not mentioned. This was in addition to the right to recoup 100% of drilling, testing, completing, equipping and operating costs. Under the revised statute, the risk charge remains at 200% of drilling, testing and completing costs for unit and substitute unit wells. Act 743 sets the risk charge at 100% of drilling, testing and completing costs for alternate unit wells. Cross-unit wells are specifically mentioned by the Act 743 as well, and the risk charge depends on whether the cross-unit well is a unit or substitute unit well (200%) or an alternate unit well (100%). Again, collection of these risk charges is in addition to the right of the drilling party to recoup 100% of drilling, testing, completing, equipping and operating costs. Who is responsible for paying the royalty and overriding royalty burdens under the nonparticipating owner’s lease during recoupment period? Under the old statute, during the recoupment period, the nonparticipating party was solely responsible for royalties created out of its working interest, and was required to make those payments out of pocket, that is, without any reimbursement from the drilling owner. Drilling parties had no liability to these royalty and overriding royalty owners if they were not co-owners of the lease or co-assignors of the overriding royalty in question. The nonparticipating party is still directly responsible to its royalty and overriding royalty owners under the new statute. However, in a dramatic change, Act 743 provides that the nonparticipating party is now “entitled to receive from the drilling owner…that portion of production due to the lessor royalty owner under the terms of the contract or agreement creating the royalty…” There is no limit on the royalty percentage for the base royalty due under this new provision. Similar new provisions of the statute apply to the overriding royalty due under the nonparticipating owner’s lease; however, the overriding royalty payment due under the new statute involves a somewhat complicated formula. Basically, the nonparticipating party is 3255504.1 entitled to receive from the drilling owner its overriding royalty burdens, but only to the extent that the sum of the nonparticipating owner’s base royalty and overriding royalty does not exceed the drilling owner’s unit weighted average total royalty burden (base royalty and overrides). The nonparticipating party receives this payment “for the benefit of his lessor royalty owner” and “for the benefit of the overriding royalty owner.” The amounts for the royalty and overriding royalty are calculated based on the agreements “reflected of record at the time of the well proposal.” These amounts are excluded from the revenue side of the equation in determining when the drilling owner has fully recouped all costs recoverable under the statute. What information regarding production must the drilling owner provide to the nonparticipating owner? Under the old statute this question was not addressed; the statute contained no specific provisions for providing production data or proceeds of production other than what is reported to the Office of Conservation. Now, the revised statute provides that when the drilling owner delivers to the nonparticipating owner “the share that is to be received,” the drilling owner must also provide all the information that La. R.S. 31:212.31 requires a mineral lessee to provide its royalty owner when making royalty payments. During the recoupment period, what remedies are available to the royalty and overriding royalty owners of the nonparticipating owner for nonpayment to them of their royalties? The prior version of the statute did not specifically address this question. Royalty and overriding owners had available to them special procedures in the Mineral Code which require prior written notice, response or payment within 30 days, and consequences for failure (double royalty penalty, attorney fees, interest, and in rare cases lease cancellation). But those special procedures applied only as between these royalty or overriding royalty owners and the nonparticipating owner. Act 743 specifically incorporates those special Mineral Code non-payment procedures into La. R.S. 30:10 to be applicable to royalties accruing during the recoupment period, but specifically provides that the nonparticipating owner’s royalty and overriding royalty owners have those same remedies not only against the nonparticipating owner, BUT ALSO AGAINST THE DRILLING OWNER. Because there is no contractual relationship between the nonparticipating owner’s royalty/overriding royalty owners and the drilling party, there are significant uncertainties about how this procedure will be applied. A specific provision of the statue prohibits a cause of action against the drilling owner if he “provides sufficient proof of payment of the royalties to the nonparticipating party.” 3255504.1 During the recoupment period, what are the remedies available to the nonparticipating owner for nonpayment to him by the drilling owner of the amounts required for the benefit of his royalty and overriding royalty owners? This is an entirely new provision because under the old statute no such payment was due. Under the changes enacted by Act 743, if the nonparticipating owner pays his royalty/overriding royalty owners, and the drilling party fails to pay the nonparticipating owner the statutory amounts due, then a claim is made using a new special procedure. Similar to the procedure available to an overriding royalty owner for nonpayment, this new procedure requires prior written notice of nonpayment by the nonparticipating owner to the drilling owner, and gives the drilling owner 30 days to pay or state a reasonable cause for nonpayment. If he does neither, the court may award as damages double the royalty due, interest and reasonable attorney’s fees. If the nonparticipating owner has not paid his royalty/overriding royalty owners, and the drilling party has not paid him, he likely can still make demand for payment on the drilling owner and file suit to collect under the general law and procedures applicable for collection of debts. He may be entitled to the same damages that any creditor generally may get in a suit to collect monies due by statute or under a contract. What are the rights/liabilities as between the drilling owner and a working interest owner in the unit who has not been given a “risk fee” notice? Under the prior statute the unnotified working interest owner could not be assessed a risk charge, but the drilling owner could still recoup unit well costs from 100% of his production before having to deliver production or proceeds to such a party. In addition, the unnotified working interest owner had to pay his royalty and overriding royalty owners out-of-pocket. The law remains the same in that it does not assess a risk charge to the unnotified owner. And the drilling owner recoups his unit well costs from 100% of production less and except royalties and overriding royalties (subject to some statutory limitations). But the statute now requires the “participating owner” to deliver to the unnotified owner “the proceeds attributable to his royalty and overriding royalty burdens as described in this Section.” Note that the statute uses the term “participating owner” here instead of “drilling owner,” which is used everywhere else in the statute; this variance in terminology may merely be an insignificant oversight. The statute also uses the term “proceeds” here, rather than “portion of production,” so the option of delivery in kind may not be available under this provision. 3255504.1 May the drilling owner satisfy these new obligations to the nonparticipating party during the recoupment period by delivery “in kind” to the nonparticipating party (or a third party purchaser for his benefit) rather than payment of proceeds? The drilling owner, more likely than not, will be able to satisfy its obligations during the recoupment period by delivery in kind, but the language in different parts of the statute is inconsistent as to this point. Do any of these new provisions apply to existing wells, and if so, how? The Legislature did not provide an effective date in the statute, meaning August 1, 2012 is the default effective date. Because this new statute makes a substantive change to the law—as opposed to a procedural or interpretive change—it cannot be applied retroactively. But even if a court were to determine that the changes were merely procedural or interpretive, a retroactive application would still likely be found unconstitutional, as it would divest operators of vested rights and/or impair previously existing contractual obligations. 3255504.1