'Sequentialism' or 'Gradualism'? On the Transition to Democracy and

advertisement

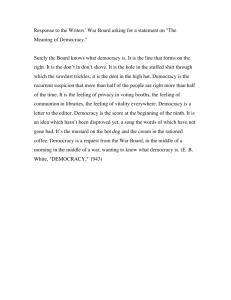

National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century Working Paper No. 38 'Sequentialism' or 'Gradualism'? On the Transition to Democracy and the Rule of Law Malcolm MacLaren University of Zurich ml.maclaren@utoronto.ca October 2009 'Sequentialism' or 'Gradualism'? On the Transition to Democracy and the Rule of Law Malcolm MacLaren*, University of Zurich Abstract How can autocracies be transformed to functioning democratic states? This question is considered in the framework of a high-profile debate about democratic sequencing. The debate, waged in the Journal of Democracy between Thomas Carothers and Edward D. Mansfield / Jack Snyder, concerns whether the rule of law and state capacity should be established before electoral reforms are introduced. The transition strategies that they advocate – 'gradualism' and 'sequentialism' – are closely examined in the following paper and are shown to have several serious shortcomings. Unless such strategies are more rigorously conceptualized and supported, their prescriptive power for democracy promotion will remain doubtful. Keywords Democracy Promotion, Democratization, Transition Strategy, Sequentialism, Gradualism * Malcolm MacLaren is a Habilitand at the Faculty of Law of the University of Zurich and has been a Post-doctoral Fellow in the project "Democratizing divided societies in bad neighbourhoods" of the Swiss National Center of Competence in Research (NCCR) - 'Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century'. The author thanks Professors Daniele Caramani (University of St. Gallen), Lars-Erik Cederman (ETH Zurich), and James W. Davis (University of St. Gallen) for their comments on drafts of the paper. 2 Introduction An unknown, likely apocryphal, Irish priest was asked by a parishioner how to get to Heaven. He replied, "Oh, there are many ways – but you cannot start from here!" The question put to the priest is analogous to the question that concerns us here – namely how autocracies can be transformed to functioning democratic states – and to two ways that have been proposed – the transition strategies 'sequentialism' and 'gradualism'. This question of how to get to democratic heaven will be considered through analysing a debate about democratic sequencing waged between prominent writers in the influential Journal of Democracy (J. of D.).1 The pieces of Thomas Carothers, Edward D. Mansfield and Jack Snyder address whether a general theory of democratization is ascertainable; whether there are any conditions necessary for successful democratization; whether such conditions should be pursued prior to or at the same time as political change; and most intriguingly, whether policy recommendations can be made in specific cases. The following discussion critiques the debate about democratic sequencing, demonstrating its various but all serious shortcomings. How exactly democracy emerges and how its success may be ensured are beyond my expertise. As will be shown, however, autocracies are not going to reach democratic heaven through the transition strategies 'sequentialism' and 'gradualism' alone. The wider context Before turning to this debate, I should place it in a wider context. This context explains why understanding the transition to democracy is imperative. Contemporary efforts to promote democracy internationally are now a well-established item on most Western governments' foreign policy agenda, be it for reasons of idealism (democracy is a proverbial 'good thing') or realism (non-democratic states pose security threats).2 George W. Bush's 'grand vision' of democracy around the world and his pursuit of a 'forward-strategy' with the use of force if necessary is the best-known case. Actual progress in promoting democracy has, however, been meagre, including in Afghanistan and Iraq. Indeed, these efforts must now be as much concerned with consolidating democracy as with spreading it, since at least half of the world's young democracies are struggling to prevent 1 The debate has been waged between Carothers on one hand and Mansfield and Snyder on the other, with contributions from Sheri Berman and Francis Fukuyama, in the January and July numbers of the Journal of Democracy, 2007 (Vol. 18, No. 1 and 3). 2 Further see Giovanni M. Carbone, Do all good things go together? The political, economic and social consequences of democratisation (Paper presented at the Annual National Conference of the Midwest Political Science Association (MPSA), 3-6 April 2008, Chicago, at http://air.unimi.it/bitstream/2434/37232/1/%C2%B0Do+all+good+things+go+together+(MPSA,+140308).pdf). 3 their democratic institutions being reversed.3 (Examples include Bolivia, Fiji, Honduras, Madagascar and Thailand.) Describing the current state of democracy or its development over time is a prerequisite to contemporary efforts to promote democracy internationally. Yet such measurements from Freedom House or Polity IV4 do not tell us about the 'whys' and the 'hows' of democratization. Likewise, observers may agree that there are many factors that can challenge5 the democratization of autocratic political systems. While also essential to effective democracy promotion, drawing correlations does no more than suggest causalities.6 It does not tell us how these relations work, and it does not prescribe transition strategies or concrete policy recommendations. Finally, understanding the transition to democracy is imperative not only due to the prevalence of promotion efforts and the complexity of the process but also due to the high stakes involved. Democratization is typically long, arduous and risky. Sometimes it does succeed: events unfold peacefully and a durable (pluralistic) democracy is founded. History is, however, riddled with examples in which it has gone awry. The elections are not free and fair, but are marred by threats, bribery, fraud and bloodshed. The results are variously 'pseudo democracies',7 the further destabilization of already instable societies, and even armed conflict, internal and/or external.8 Democratization theories The United States has long been the principal promoter of democracy worldwide, from its failed attempt after World War One 'to make the world safe for democracy' to its as yet undecided attempt to democratize Iraq. The issue of transition strategies and the debate about democratic sequencing have accordingly galvanized its foreign policy community. 3 Further see Nathan Converse and Ethan B. Kapstein, "The Threat to Young Democracies", 50(2) Survival (AprilMay 2008), p. 127-140, 127. 4 See http://www.freedomhouse.org and http://www.cidcm.umd.edu/polity, respectively. 5 If the legitimacy of democracy as a form of governance is based on responsiveness qua popular participation and accountability qua political effectiveness, factors challenging democratization may be considered to include the following. As regards 'input legitimacy', these are the demos dilemma (i.e. the unsettled bounds of the polity), cultural diversity (the compatibility of multiethnic societies and representative democracy), socio-economic wellbeing and inequality (the role of poverty and skewed wealth distribution) as well as civil society (limited extent of voluntary associational life outside the state and the economy). As regards 'output legitimacy', these are the difficulty of improving the rule of law and other state capacity (good governance in failing or failed states) in coordination with electoral reforms. (Hanspeter Kriesi, Marc Bühlmann, Lars-Erik Cederman, Frank Esser, Wolfgang Merkel and Yannis Papadopoulos, "Challenges to Democracy in the 21st Century", NCCR Working Papers, No. 7 (June 2007), p. 20 et seq., at http://www.nccrdemocracy.uzh.ch/nccr/publications/workingpaper/pdf/WP7.pdf.) 6 Further see Charles Tilly, "Processes and Mechanisms of Democratization", 18(1) Sociological Theory (2000), p. 1-16. 7 i.e. political charades, systems that have not been chosen by the population, that lack accountability, that are self-serving, that oppress minorities etc. 8 Further see Lutz Krebs, Dominic Senn and Judith Vorrath, "Linking Ethnic Conflict & Democratization: An Assessment of Four Troubled Regions", NCCR Working Papers, No. 6 (June 2007), especially p. 8 et seq., at http://www.nccr-democracy.uzh.ch/nccr/publications/workingpaper/pdf/WP6.pdf. 4 Despite the long tradition of democracy promotion, US academics, like US politicians, still have considerable difficulties in dealing with the issue. They have yet to achieve a shared understanding about how democracy emerges, let alone about how to ensure its success. Four general theories have at various times been influential in the country's foreign policy community: a democratic universalist approach (theories that assume that all societies want and are capable of democracy, largely regardless of historical or contemporary conditions),9 a sociological approach (theories that argue that certain cultural and social transformations must occur in a society before democracy is viable and sustainable),10 a rational choice approach (theories that consider democratization primarily as a collective action problem involving different interests of political actors)11 and the sequentialist approach. Sequentialist approach As explained, it is the sequentialist approach – its foundations and implications – that concerns us here. Contemporary sequentialism may be traced back to Seymour Martin Lipset's book Political Man of 1963,12 in which he drew a strong correlation between economic factors and the emergence of democracy. Samuel Huntington in turn criticized the claim that economic development leads to political stability and emphasized the importance of establishing state capacity instead.13 Both scholars believed, however, that there is an ideal sequence for democratization: successful democratization is more likely if it follows well-defined steps, namely increasing wealth and economic equality or accumulating state power before elections are held. The sequentialist approach had a vogue in the US foreign policy community until the 'third wave' of democracy in the mid-1970s. The third wave, during which authoritarian regimes around the world were replaced by democracies irrespective of level of development, seemed to undermine sequentialist assumptions and support democratic universalism's. The experience of next two decades, in which many third-wave democracies struggled and some failed, led to sequentialism's revival, most prominently in the work of Fareed Zakaria. In The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad (2003),14 Zakaria warned against holding elections before certain conditions are fulfilled. The introduction of 9 Formatively see Dankwart Rustow, "Transitions to Democracy: Toward a Dynamic Model", 2(3) Comparative Politics (1970), p. 337-363. 10 Formatively see Gabriel Almond and Sidney Verba, The Civic Culture (Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 1963), as well as Harry Eckstein, Division and Cohesion in Democracy – A Study of Norway (Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 1966). 11 Further see Adam Przeworski, Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991). 12 Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man (Garden City (NJ): Anchor Books, 1963). 13 Samuel Huntington, Political Order in Changing Societies (New Haven (CT): Yale University Press, 1968). 14 Fareed Zakaria, The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003). 5 democracy may otherwise lead to the retrenchment of constitutional liberalism rather than its establishment, he argued, citing Putin's Russia and Chavez's Venezuela. Zakaria further argued that economic development encourages constitutional liberalism but that in order to enjoy economic development, sufficient state capacity must exist first: "without a government capable of protecting property rights and human rights, press freedoms and business contracts, antitrust laws and consumer demands, a society gets not the rule of law but the rule of the strong".15 In view of the difficulties of US democracy promotion efforts in Iraq, scholars such as Larry Diamond have emphasized the importance of constructing a strong state for the sake of security: a minimum of order on the ground is necessary for any economic or democratic progress at all in a postconflict situation in which the state has collapsed. Without order, elections will revive autocracy and may trigger large-scale armed conflict. "The first lesson", argues Diamond, "is that you cannot get to Jefferson and Madison without going through Thomas Hobbes".16 The debate itself The debate about democratic sequencing has been continued between academic and political heavyweights17 in the J. of D. The article by Carothers "How Democracies Emerge: The 'Sequencing' Fallacy" set off the debate by challenging the alleged need for democratic sequencing. Carothers criticizes the view prevailing in the US foreign policy community that certain conditions, especially the rule of law and state capacity, should be in place in a country before democratization is attempted. Specifically, he questions the relative compatibility of authoritarianism versus democracy with rule-of-law development and statebuilding. Carothers argues that electoral reforms should be introduced gradually in tandem with the other reforms. In contrast, Mansfield and Snyder have warned against pressing too quickly and incompletely for democracy, emphasizing the inadvertent, costly effects of failed democratization, including possibly triggering conflict. They argue that the international community should give less priority in transition strategies to enhancing popular political participation and more to establishing basic state functions. 15 Ibid., p. 76-77. Larry Diamond, Squandered Victory: The American Occupation and the Bungled Effort to Bring Democracy to Iraq (New York: Times Books, 2005), p. 305. 17 The dust-jacket of Carothers' book, Critical Mission: Essays on Democracy Promotion (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2004), describes him as "the world's leading authority on democracy promotion". Mansfield and Snyder are credited with the influential idea that the risk of war increases in the early stages of a state's democratization. (Further see Edward D. Mansfield and Jack Snyder, "Democratization and the Danger of War", 20(1) International Security (1995), p. 5-38.) Fukuyama is renowned for his essay "The End of History?" (16 National Interest (Summer 1989), p. 3-18) and for his ties to neoconservatives in George W. Bush's administrations. 16 6 This paper does not attempt to settle the sequencing debate. Its aim is more modest, namely to demonstrate the debate's lack of rigor. I realize that the J. of D., in its editors' words, is "not an exclusively academic journal, sheathed in social-science shibboleths" but is proud to be one of the most widely read publications about democracy internationally.18 Even judged as popular scholarship, however, the J. of D. pieces are inadequately conceptualized and supported. Their shortcomings, though inter-related, are analytically separable as follows: - Definitionally vague. What exactly is the goal of each of the transition strategies presented, and when exactly will this goal be reached? In short, what is 'success'? Qua definitione "gradualism", "sequentialism" and "democratization" all have an objective and an endpoint; the strategies offer the route. The pieces do not indicate these, since they lack precise definitions of 'democracy' and for that matter, 'rule of law'.19 This lacuna is not a matter of mere semantics but is fundamentally problematic. These terms are contested and can be used to support many different arguments. (For example, there seems to be almost as many definitions of democracy today as there are states calling themselves democracies, including 'The Democratic People's Republic of Korea' – a.k.a. North Korea.)20 Further, these terms must be articulated and evaluated not only singly but also together if they are to be ascertained: democracy and the rule of law can qualify the extent of as well as complement the effectiveness of one another. (A 'thick' as opposed to a 'thin' definition of the rule of law already links the concept inextricably to democracy and liberty.21) Put otherwise, it is evident that the debaters' definitions differ,22 but how exactly is not, since the debaters fail to present their own and address each other's premises thoroughly. One wonders whether much of the debate would have been avoided, if Carothers, Mansfield and Snyder had argued on the basis of common understandings. Depending on these, the establishment of democracy and the rule of law would a priori be an integral, reciprocal process or different, separable phases of political development. 18 See the J. of D. website at http://www.journalofdemocracy.org/about/authors.html. Reference is presumably to be made to Carothers' and Mansfield and Snyder's earlier writings like Critical Mission (supra) and Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War (Cambridge (MA): MIT Press, 2005), respectively. 20 The debaters tend to define democracy according to whether or not periodic, free and fair national elections based on universal suffrage are held. (E.g. see Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 12 et seq. and p. 26; Mansfield and Snyder, J. of D. July 07, p. 5.) 21 Further see Michael J. Trebilcock and Ronald J. Daniels, Rule Of Law Reform And Development (Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008), p. 12 et seq. Also see Daniel Thürer and Malcolm MacLaren, "In and around the Ballot Box: Recent Developments in Democratic Governance and International Law put into context", in: Marcelo G. Kohen (ed.), Promoting Justice, Human Rights and Conflict Resolution through International Law (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2007), p. 549-568, especially p. 558 et seq. 22 For example, contrast: "the history of the established Western democracies is in many places a story of their simultaneous development and mutual reinforcement" (Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 18) with "Great Britain's nineteenth-century path towards mass electoral politics was smoothed by the preexisting strength of its legal system, representative institutions, and free press" (Mansfield and Snyder, J. of D. July 07, p. 5). 19 7 - Normatively uncertain. The normative content of the democracy and rule of law that the debaters aspire to is not made clear. A constitutional liberal democracy would surely be acceptable to all, but would a Rawlsian decent hierarchical society?23 The degree to which one holds liberal values dear influences one's preferences among transition strategies. (If democracy is considered a post-materialist good, for example, the military juntas that long ruled Chile, South Korea and Taiwan and that brought economic liberalization before political liberalization would be acceptable.) These values are, however, not expressly taken into consideration by the debaters. It must be inferred that sequentialists are sceptical not only about democracy's chances but also about its worth.24 While democracy and the rule of law seem to Carothers to be the best means of governance,25 he is cautious in his encouragement and ready to qualify his support.26 By not discussing its normative aspect, the debaters treat the topic of transition as if it were a mere technical concern. - Too rhetorical. The '-isms' in the pieces may be convenient and even catchy, but these buzz-words obscure more than they clarify. Starting from the much larger concern about the transition to democracy and rule of law, the exchange between Carothers and Mansfield and Snyder ends in a semantic disagreement about what gradualism means.27 Carothers' best explanation of his strategy is as follows: "gradualism [...] aims at building democracy slowly in certain contexts, but not avoiding it or putting it off indefinitely [like sequentialism]"; gradualism involves "reaching for the core element now, but doing so in iterative and cumulative ways rather than all at once [as in a rush to elections]". Despite having read the pieces several times, I remain unsure how gradualism is 'fundamentally different' from sequentialism.28 Gradualism, like sequentialism, is a variety of incrementalism, in speed if not in matter. Democratization remains a flexible, differentiated process of controlled reform; both strategies focus on the means and not on the end of democratization, and both provide for discretion in introducing reform. Finally, gradualism and sequentialism put a lot of faith in the power of policymaking to engineer a properly ordered democratization, i.e. to manipulate events, control dynamics and shape change. One ultimately wonders to what extent the debate is just a bickering about buzz-words. 23 Further see John Rawls, The Law of Peoples (Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 4. Similarly see Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 27. 25 Carothers claims that a "genuine, often powerful impulse toward democracy" exists among people worldwide and that gradualism serves "a belief in democratic possibility". (Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 20 and p. 27, respectively.) 26 For example, Carothers allows sequentialists to place authoritarianism and democracy on the same normative scales, in arguing that sticking with an existing autocratic regime is the better alternative in some countries. 27 Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 14 and p. 25. 28 Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 26. 24 8 - Parochial. There is an extensive theoretical and empirical literature on the topic and, as Berman documents, on the topic from these perspectives.29 Why was it referred to so sparingly and selectively by the debaters? (Especially in its second iteration, the debate is largely conducted according to own thoughts and prior works.30) Reference to this literature would have provided a broader empirical basis for the discussion and have cast doubt on several assumptions and arguments common to the debaters.31 Instead, their pieces lack depth and nuance, which undermines the debaters' claims to their strategy's insights and usefulness. The debate is also parochial in that it is focussed almost exclusively on US foreign policy, its aims and its achievements. Carothers et al. fail to consider the considerable efforts of other Western actors to promote democracy, most notably the European Union.32 What lessons does the EU's experience have to offer: how (through which mechanisms) and to what effect (extent of positive impact in target countries) does the EU promote democracy in its near abroad?33 Similarly, the debaters assume that outsiders know best, be it individual states or international organizations. Their strategies provide for no local participation, despite the fact that locals have often faced the challenges of democratization for decades.34 In short, the view here is resolutely that of the Beltway. - Another 'third way'? 'Gradualism' is described by its author as "a middle path" between unrealistic calls for sudden political openings and excessive praise for minor electoral reforms.35 Carothers seems to see himself as a modern-day Fabian of democracy, an advocate of creeping, rather than revolutionary, political change. In doing so, he sells the power of democracy too short. The relationship between 'pre'conditions and democratization may not be in one direction alone but may be mutually reinforcing. (For example, scholars have cogently argued that state capacity is positively related to the level of democracy: elections help establish the legitimacy necessary to create new institutions.36) Moreover, his strategy seems too clever by a half. Harassment and attrition against entrenched 29 Berman, J. of D. January 07, p. 39 et seq. Carothers does mention Amy Chua, Marina Ottaway and Fareed Zakaria as additional sequentialists. 30 This is most strikingly so with Fukuyama, whose piece contains no references whatsoever. 31 Among many see Michael Bratton and Eric Chang, "State building and democratization in sub-Saharan Africa: forwards, backwards, or together?", 39 Comparative Political Studies (2006), p. 1080 et seq. 32 In all the pieces, democracy promotion by EU is only mentioned once and then in passing (Mansfield and Snyder, J. of D. July 07, p. 9). Berman's title, "Lessons from Europe", is in this sense misleading: her first piece is essentially a history of the democratization of Western European states up to World War II. 33 Further see results of the ongoing research of another NCCR-Democracy project, Promoting democracy in the EU and its near abroad, at http://www.nccr-democracy.uzh.ch/nccr/research/modul1/ip2. 34 Mary Kaldor puts it starkly: "The only way to discover whether […] elections should come first or later, is through publication consultation and debate". (Mary Kaldor, "Book Review", 47(4) Survival (2005), p. 175.) 35 Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 26. 36 For example, see Philippe C. Schmitter with Claudius Wagemann and Anastassia Obydenkova, Democratization and State Capacity (Paper presented at the X Congreso Internacional del CLAD sobre la Reforma del Estado y de la Administración Pública, October 18-20 2005, Santiago de Chile, at http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/CLAD/clad0052201.pdf). 9 authoritarian regimes seem unlikely to enjoy the success intended,37 and putting democratization off for 'a better day' may paradoxically lessen the chances of its being successfully introduced later on. Carothers' own accusation of inadequacy against sequentialists rebounds upon him: "Whatever might be theoretically preferable regarding paths of development, people in many parts of the world want to attain political empowerment now, not at some indefinite point in the future".38 'Gradualism' may be better described as an illusory ‘third way’, i.e. as a misguided and impracticable attempt to transcend previous approaches. - Limited usefulness. The perspective taken and the policy recommendations are – on both sides – so narrow as to limit drastically the usefulness of the whole debate. Debating correct timing is pointless when there is no demos out of which to make a constitutional liberal democracy or when the state concerned has collapsed completely. (As Carothers concedes, a nation and its borders must have been settled and a minimum of state capacity, especially to coerce, must be at hand before democracy can be successfully introduced.39) When in contrast the country possesses a range of 'facilitating conditions', open national elections can follow without undue delay since stable democracy is likely to develop there.40 The real debate, as Berman notes, is "about the likely political trajectories of those countries in between and what if anything outsiders can do to affect them".41 Even so, the use of debating correct timing is limited. If the circumstances (political, social, economic, cultural etc.) of the transition are significant and can vary significantly from one country to another,42 policy recommendations must be custom-tailored to them to have any hope of being effective. Transition strategies are then relative, not optimal and universally applicable.43 Finally, the use of debating correct timing is questionable when both sides confess that their prescriptive powers are modest: the full operationalization of the strategies might bring unwanted side- 37 Consider also that gradualism like sequentialism can be readily misused by those who are insincere about democratization: dictators can exploit the lack of an uncontested, clear-cut definition of democracy and its conditions to obstruct reform. (See Guillermo O'Donnell, "The Perpetual Crisis of Democracy", 18(1) Journal of Democracy (January 2007) p. 7.) 38 Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 23, emphasis in original. 39 Carothers, J. of D. July 07, p. 22 and J. of D. January, p. 19, respectively. Further see the case of Iraq, Diamond, p. 305 et seq. 40 Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 25. 41 Berman, J. of D. July 07, p. 14. 42 To elaborate: various factors encouraging or hindering democratization can be at play in states undergoing democratization. For example, a long bourgeois tradition, high literacy, exposure to the Western Enlightenment, prior experience with democracy, and democratic neighbors seem to make a transition to democracy much more likely after the fall of a dictatorship than a transition to a new autocracy. (Kristian Skrede Gleditsch and Jinhee Lee Choung, "Autocratic transitions and democratization", at http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/~ksg/papers/gleditsch_choung_2004.pdf.) 43 Carothers downplays the role of such factors in determining the success of democratization, referring to them not as "preconditions", but as "core facilitators or nonfacilitators" that make democracy "harder or easier" (Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 24). 10 effects and would not prevent democratization from ever going awry.44 In light of past experience, however, it is appropriate to be sceptical of officials’ ability (especially outside the country) to engineer democratization to the degree that the strategies require. In short, a general model for successful democratization is unascertainable: democratization is a process that involves many variables, for which there are few, if any, 'best practices', and whose outcome is inherently contingent. - 'Written in water'. In summarizing the 'waves' of democracy and the 'waves' of conventional wisdom about transition,45 Carothers recognizes that the facts on the ground and the theories in ivory towers are constantly changing. He does not, however, follow this recognition to its logical conclusion in framing his policy recommendations. He – and the other debaters for that matter – live too much in the moment.46 The real-world consequences of applying particular theories of democratization take time to make themselves plain.47 (This is especially true of sequentialism and gradualism, as both argue for introducing electoral reforms slowly.48) The debaters also lack historical perspective regarding the analysis of such consequences. They fail to consider that if all is 'written in water', their grand pronouncements may be 'washed away' as well. They react merely to the latest reading of the situation and interpretation of its meaning, rather than waiting awhile before passing judgment. The knowledge that over the past decade alone, four opposing views have successively held sway in the US about democracy promotion49 makes one reluctant to place too much confidence in the strategies put forward in the pieces. Conclusion How democracy emerges and how its success can be ensured are important and topical questions. If discussions about them are to be productive, however, they must be properly framed. The preceding paper has analysed two strategies of transition to democracy and the rule of law – sequentialism and gradualism – from a debate in the Journal of Democracy. Even when judged as popular scholarship, this debate was demonstrated to lack rigor. It does not carefully present ongoing scientific research and reflection for the benefit of a wider 44 E.g. Mansfield and Snyder, J. of D. July 07, p. 7; Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 26. Carothers, J. of D. January 07, p. 24. 46 Similarly see Berman, J. of D. January 07, p. 38. 47 A recent history of democratization around the world has found that "[e]ven the successes require two or more decades beyond the initial appearance to become consolidated." (Further see Bruce E. Moon, "Long Time Coming: Prospects for Democracy in Iraq", 33(4) International Security (Spring 2009), p. 115-148, especially p. 147.) 48 Compare: "State building, creation of a liberal rule of law, and democracy […] in most European countries occurred in a sequence that was separated by decades, if not centuries." (Francis Fukuyama and Michael McFaul, "Should Democracy Be Promoted or Demoted?", Washington Quarterly (Winter 2007-08), p. 31.) 49 Further see Berman, J. of D. January 07, p. 29 et seq. 45 11 public. It instead oversimplifies a complex topic and exaggerates the policy implications. In the final analysis, one wonders how much is actually understood of the dynamics and mechanisms at play in states that are democratizing, and more, how much these can actually be controlled by outsiders promoting democracy.