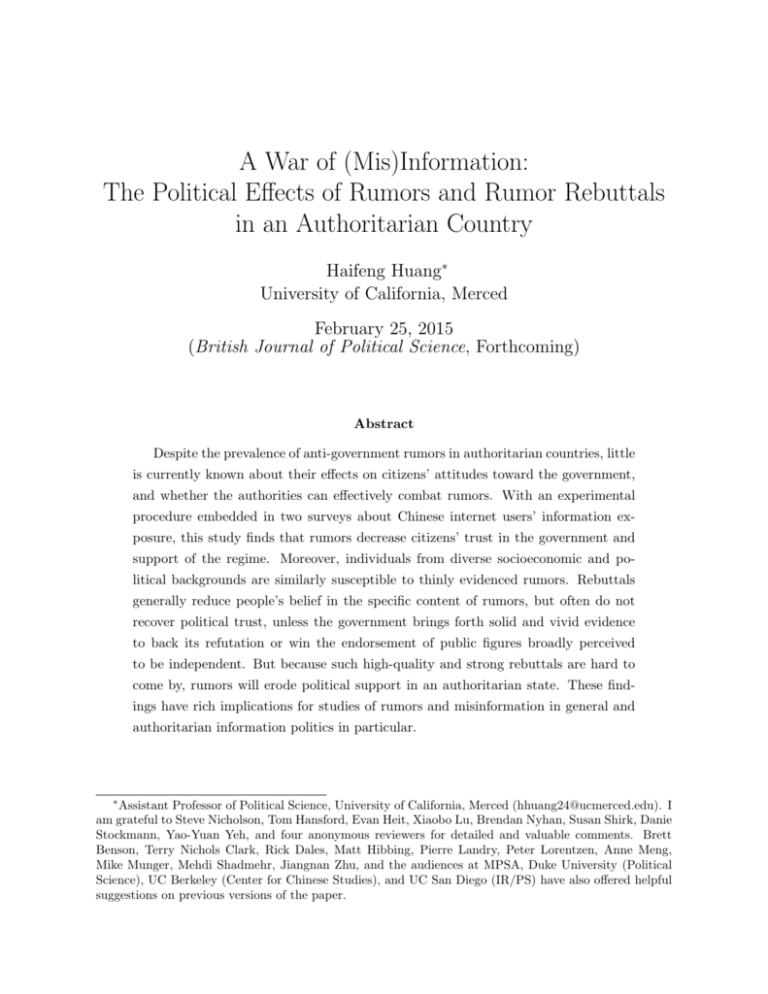

The Political Effects of Rumors and Rumor Rebuttals in an

advertisement