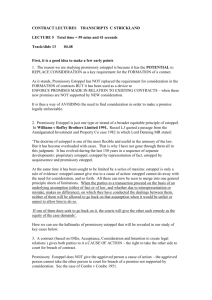

The Many Faces Of Promissory Estoppel

advertisement