Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

ENGLISH FOR

SPECIFIC

PURPOSES

www.elsevier.com/locate/esp

‘Small bits of textual material’: A discourse

analysis of Swales’ writing

Ken Hyland

*

School of Culture, Language and Communication, Institute of Education, University of London,

20 Bedford Way, London, WC1H 0AL, UK

Abstract

Despite his considerable influence on the development of ESP and all our professional lives,

almost nothing has been written about John Swales’ distinctive prose style. Based on a 340,000 word

corpus comprising 14 single-authored papers and most chapters from his three main books, this

paper sets out to identify the main features of this style. Using frequency, keyword and concordance

analyses, I compare the Swales’ corpus with a broader applied linguistics corpus of 710,000 words

and identify self mention, hedging and attitude, reader engagement and considerateness as characteristic of Swalesian rhetoric. I conclude with the view that this is a disciplinary voice informed

by a keen assessment of his readers and representing an independent creativity shaped by an

accountability to shared practices.

Ó 2006 The American University. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

‘‘By the late 1970s, I was also coming to the conclusion that I had some small talent

for taking unlikely, small bits of textual material of a kind many might assume to be

pretty trivial, and turning them into rather more substantive accounts than colleagues might have anticipated.’’

(Swales, 1998, p. 179)

John Swales has been the single most influential figure in the emergence of ESP as a

force in English language teaching. He has reinvented himself several times over the past

35 years, keeping one step ahead of both the field and his critics in an environment which

*

Tel.: +44 20 7612 6789; fax: +44 20 7612 6534.

E-mail address: k.hyland@ioe.ac.uk.

0889-4906/$34.00 Ó 2006 The American University. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.esp.2006.10.005

144

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

has not always been hospitable to his innovative approaches to language description and

pedagogy. Almost single-handedly at first, he carved a distinct space for ESP by insisting

that language use is always related to social contexts and that practice should always be

firmly grounded in theory. These ideas often struggled in a world where prevailing fashions focused on an idealized linguistic competence and psycholinguistic notions of acquisition and learning. The fact that the concepts of genre, discourse analysis, textography,

community and consciousness raising have now established themselves, and in many cases

supplanted these earlier ideas, is testament to Johns’ defining influence on the field. But

while some considerable effort has been spent in extending, elaborating or challenging

Swales’ ideas, less has been said on his writing style and the language he has employed

to construct his ideas and reputation.

In this paper I squeeze into this, admittedly very narrow, research gap to explore how

John uses language to position himself, present his ideas and interact with his readers. Such

acts of self-representation are sometimes referred to as voice, stance or persona, but unlike

some treatments in rhetorical and literary-critical theory, I do not see this as just an individual expression of authoritativeness or authorial presence. On the contrary, all writing

contains ‘voice’ as it is this which situates us culturally and historically and allows us to

locate ourselves in our communities through the linguistic resources our disciplines make

available. But as John’s writing reveals, these culturally recognisable forms do not produce

a conformity to rigid prescription but represent boundaries broad enough to allow even the

most individual, even eccentric, individuals to engage their colleagues effectively.

Using techniques from corpus linguistics and a predilection for the features of interaction in texts, I interrogate a 340,000 word corpus of John’s published writing to characterise something of the Swales’ style and his use of language to establish himself and his

views. In particular, I focus on what appears to be the central features of this corpus as

revealed through frequency, keyword and concordance analysis: that is, a highly personal,

modest and interactive style. To begin with I look at some of his preferred terms and make

comparisons with a larger applied linguistic corpus to see what distinguishes his work

from the herd, but first, a few words about the corpora.

1. Corpora and methods

The ‘Swales corpus’ (Appendix) was compiled at the English Language Institute (ELI)

from John’s collection of work. It consists of 14 single-authored papers and most chapters

from his three main books: Genre Analysis (1990), Other Floors, Other Voices (1998) and

Research Genres (2004). It therefore represents 15 years of Swales’ research output in various forms and comprises 342,500 words in all. My intention is to identify some of the distinctive features of this work by comparing it with a broader applied linguistics corpus

using frequency, keyword and concordance analyses. The reference corpus represents a

spectrum of current work in the area and mirrors the genres of the Swales collection, comprising 66 research articles from 15 leading international journals and 25 chapters from 12

books totalling 710,000 words.

The text processing for this research was done with Wordsmith Tools 4 (Scott, 1998).

The first step was to generate word lists of single words, and three-, four- and five-word

strings for the two corpora, narrowing the set of expressions by applying notions of structural and idiomatic coherence. This meant that only word clusters which constituted complete syntactic units or which intuitively seemed like idiomatically independent expressions

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

145

were included. Examples of syntactically complete units include prepositional phrases (at

the outset, in the context of), noun phrases (an interesting concept, the last ten years), verb

phrases (to confirm our, consider this example) while sentence stems are phrases such as: I

think that, it is well known that and we suspect.

I then compared each list in the Swales corpus with those from the reference corpus

using the KeyWords tool. This program identifies words and phrases that occur significantly more frequently in the smaller corpus than the larger using a log-likelihood statistic

to determine whether the frequency difference is statistically significant (at a 0.000001 significance level). This offers a better characterisation of the differences between two corpora

than a simple comparison of ranked frequency lists as it identifies items which are ‘‘key’’

differentiators across many files, rather than being dominated by the most common words

in each corpus. In this way, I could identify which words best distinguish the texts in the

Swales corpus from those in applied linguistics more generally. After reviewing the keyword lists and identifying individual words and multi-word clusters, I then explored the

more frequent items through concordancing. This allowed me to group common devices

into broad functional and pragmatic categories which seemed to capture central aspects

of Swales’ writing.

2. Frequency and keyword features: genre, dissertation and herbarium?

A simple frequency count of content words throws up items which might lead us to

identify John in a ‘name-the-linguist’ parlour game. The top eight content items are:

research, genre(s), English, discourse, language, academic, writing and students. All these

items occur over 500 times and, like texts, community and rhetorical which appear a little

further down the list with over 300 occurrences, appear in 90% or more of the 50 files that

make up the corpus. This is perhaps not surprising as they represent the key themes of

Swales work and serve as motifs for his contribution to the field, as do several of the most

common n-grams, or multi word clusters, which include non-native speakers of English, the

concept of discourse community, a genre based approach and English as a second language.

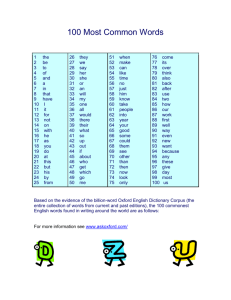

A Keywords list generated by comparison with the reference corpus, as shown in

Table 1, offers a more accurate indicator of the words and clusters which best distinguish

Swales’ writing as these are items which occur significantly more often than chance

(p < 0.00000001).

Table 1

Keywords in the Swales corpus

singles

3-grams

4-grams

5-grams

Genre(s)

dissertation

Herbarium

I

Michigan

Have

Species

My

Specimens

ELI

Would seem to

In terms of

Various kinds of

The research world

The English language

The fact that

At this juncture

In the herbarium

The Testing Division

The research article

the University of Michigan

English for Specific Purposes

As might be expected

As far as I

I have tried to

The North University Building

A genre-based approach

Turns out to be

Over the last decade

Have been able to

Non-native Speakers of English

The concept of discourse community

As might be expected the

The second half of the

As far as I am

At the time of writing

I have been able to

The role of English in

As far as I am aware

As far as I can

146

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

At the top of the single words list are genre, dissertation and herbarium, items which

form the core of the three monographs in the corpus. The latter of these, like species

and specimen which also figure in the top ten keywords, appears because of its location

on the second floor of the North University Building at Michigan. It was here that

Swales not only spent much of his working life, but also where he haunted the

corridors closely and sympathetically observing the lives and texts of its inhabitants

for Other Floors, Other Voices, a surprisingly under-rated book which perhaps drew

more critical than popular acclaim. Here again, the University of Michigan, non-native

speakers of English and the North University Building are the main key phrases in the

corpus.

More interestingly, the keywords programme reveals significant uses of non-content

words and phrases, which move us away from Swales’ professional interests to indicate

something of the pragmatic and discoursal features of his work. In particular, if we look

at the individual keywords and coherent n-grams, or recurrent sequences of more than one

word, we see that they cluster around four broad areas which we can characterise as (i)

hedges and mitigation markers, (ii) attitudinal lexis, (iii) reader engagement, and (iv) metadiscourse signals. The starting place for this analysis, however, is the extraordinary use of

self mention.

2.1. The personal in the rhetorical: self mention and reflection

John’s frequent use of the first person is perhaps the most striking feature of the keywords list, with both I and my occurring in the top ten. Self-referential I, me and my occur

9.1 times per 1000 words in the Swales corpus compared with 5.2 per 1000 words in the

applied linguistics reference corpus and 1.4 per 1000 words in a more general academic

corpus of 240 research articles (Hyland, 2001). This marked preference for explicit authorial intrusion helps to explain the very strong sense of personal investment we get from

John’s writing. This is not the faceless discourse which academic prose is often caricatured

to be, but a style of writing infused with the subjectivity of a writer making decisions,

weighing evidence and drawing conclusions, as can be seen from a few examples (dates

refer to papers in the corpus list in the Appendix):

(1) Like many ESP practitioners today, I believe that knowledge of any genre is best

viewed as a crucial strategic resource.

(1998b)

(2) I feel fairly confident in claiming that Herbarium curators form a distinctive community.

(1998a)

I suggest that a large part of the way forward in this pragmatic approach is to take

the view that theory and methodology represent not so much separate epistemological worlds, but function more as mirror images of the same enterprise-that of making useful discoveries.

(2004a)

A real human voice is integral to John’s style of argument: here is an actual, accountable source and not simply an anonymous animator. The personal conviction expressed in

these claims both engages the reader in the argument and acts a strong persuasive force,

investing his rhetoric with the personal and experiential, often by drawing on his own

teaching practices:

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

147

(2) My students come from every conceivable department, but I try to make them a

socio-rhetorical community, a support group for each other. I do a lot of rhetorical

consciousness raising and audience analysis. . .. I take them behind the scenes into the

hidden world of recommendations, applications and evaluations.. . . In actual fact, I

am much less sure than I used to be that I am a language teacher. I have come to

believe that my classes are, in the end, exercises in academic socialization. (1994)

We also get a sense of John thinking through issues and a clear impression of why they

matter. This is perhaps most obvious in his traipsing between departments to understand

the different community practices in Other Floors, Other Voices, but it also comes through

strongly in the kinds of reflections he shares with his readers in all his work, as in this

admission from English as Tyrannosaurus rex (1997, p. 377):

(3) So I have belatedly come to recognize a certain self-deception in 30-year involvement

with academic and scientific English. Certainly in Libya in the 1960s and in the

Sudan in the 1970s I accepted the widely-held position which argued that what Third

World countries needed was a rapid acceleration in their resources of human capital,

which could be achieved by a hurried transmission of western technical and scientific

know-how delivered through the medium of English and supported by appropriate

English language programs. I also believed that working overseas in scientific English, as researcher, materials writer and teacher, was, in essence, a culturally and

politically neutral enterprise. In doing so, I conveniently overlooked the links

between the teaching of technical languages and the manufacture and export of technical equipment. So, when I read, say, Phillipson’s counter-culture account of how

British ESL created an academic and commercial base for itself, I find myself caught

up in some serious reflection.

Clearly there is both real assurance and confident ease in this writing which perhaps

comes with experience. I haven’t been able to study diachronic changes in this corpus,

but it is widely believed that the options open to established researchers are probably

much wider than those available to beginning ones; a phenomenon John has referred to

as ‘‘Young Turk’’ versus ‘‘Old Fart’’ approaches (Swales 2002). This kind of reflexivity

contributes to the construction of a very particular ‘voice’ or rhetorical personality, a

feature which has been called stance (Biber and Finegan, 1989; Hyland, 2005). A key

aspect of the Swalesian stance is frequency with which explicit self-mention is used

in a self-deprecatory way. John himself claims this is for self-protection: a concern with

being found to be wrong about things (Swales, pc). I see method here, however as John

is unusual in revealing the often unacknowledged uncertainties and failures which plague research. Rather than airbrushing these, he almost celebrates them, perhaps promoting another Swales’ agenda: that of encouraging novice researchers and teachers

by admitting that even the field’s most illustrious figures have their doubts and

setbacks:

(4) When I started this project I kept on coming across adjectives that I felt I ought

to have known, but somehow I didn’t quite manage to resurrect their meanings (and

I suspect that I am not alone in this kind of annoying discovery).

(1998a)

148

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

But I am very unsure whether I will ever use these particular materials again. As matters stand at the moment, these materials have been, I believe, an educational

failure.

(2001b)

Indeed, despite some trying, I have so far been unable to repeat my earlier success.

Perhaps in the same way that composers only seem able to write one violin concerto,

discourse analysts can produce only one successful model.

(2002b)

More generally, a concordance of the first person in the Swales’ corpus shows the extent

to which agency is explicitly associated with modality and mitigation. The most frequent

main verbs related to I are think (86), believe (71), suspect (35), hope (33) tried, (31) and

guess (29), all of which reflect his care and circumspection in handling claims and data.

Clearly these patterns occur frequently enough to represent conscious choices in self representation, suggesting that John believes the researcher should be visible in the text. We

find similar uses when extending the collocates to the most common clusters (Table 2).

2.2. Interactional preferences: hedging and attitude

Part of this personal involvement involves a prudent approach to textual data and a

respect for the potentially opposing views of readers. John’s texts are copiously annotated

with commentary on the possible accuracy of claims, the extent of his commitment to

them and his stance towards them. Essentially, Swales does this in two main ways: through

hedging and the expression of attitude.

The use of language to express caution and commitment is a key feature of academic

writing and much has been written on the topic of hedging and boosting as communicative strategies for conveying reliability and strategically manipulating commitment for

interpersonal reasons. Writers represent themselves and their work in different ways and

this is partly influenced by discipline, by experience, by personality and by the material

they are working with. Writers must calculate what weight to give an assertion, marking the extent they regard it as reliable and perhaps claiming protection in the event

that it turns out to be wrong (Hyland, 1998). Hedges therefore imply that a statement

is based on plausible reasoning rather than certain knowledge, indicating the degree of

confidence it is prudent to attribute to it. Swales employs hedges and mitigation

throughout his work, opening a discursive space which invites readers into a dialogue

where they can consider and dispute his interpretations. As these examples suggest,

his arguments often seek to accommodate his reader’s expectations that their views will

be acknowledged in the discourse:

(5) Such observations suggest to me that looking for ‘‘a one size fits all’’ concept of

genre, searching for a single best kind of genre theory—and one doubtless that is

complex, subtle and fully nuanced—is probably misguided.

(2002a)

I was, I suspect, rather too easily seduced by the concept of discourse community.

Perhaps all too willingly I made common cause with all those who have their own

agendas for viewing discourse communities as real, stable groups of consensus holders.

(1998a)

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

149

Overall, there would seem to be some evidence that children acquire some genreskills quite early. . ..

(1990)

By marking statements as provisional in this way, John is able to both convey his views

and involve readers in their ratification, conveying respect for colleagues and their positions. The extent of this tendency towards rhetorical modesty can be seen from the list

of hedging expressions which occur in the top 500 keywords in the corpus shown in Table

3, all of which are statistically highly significant.

Despite this emphasis on negotiation and reader awareness, Swales is no wilting violet. He has always listened to his critics and revisited several of his more well-known

arguments, notably those on the move structure of introductions, on the nature of community, on purpose in defining genre, and on English on the world stage. His work,

however, could never have been so influential if it was nothing more than a series of

self-effacing invitations for us to consider possibilities. He is also able to present claims

with unambiguous robustness:

(6) Certainly, any kind of descriptive approach to communication is a badly needed

input into HRD as it is currently practised and understood.

(1994)

The key point I want to make here is that when matters do not go smoothly, we can

find opportunities within encounters for conversation management.

(1993)

Some shift in the reading research area towards a genre perspective would seem

highly desirable.

(1990)

. . .any vision we may have of the scientist-researcher working away in the lab or in

the field and then retiring to a quiet place to type up quickly the experimental report

according to some stereotyped format is decidedly at odds with reality.

(1990)

Table 2

Most frequent collocates of ‘I’ in the Swales’ corpus

I

I

I

I

have * tried to

believe (in parenthesis)

would like to

(would) suggest

30

30

28

22

As far as I am aware/know

As far as I can tell/see/discover

I would argue

I have attempted to

16

13

10

8

Table 3

hedging expressions in the corpus (p < 0.00000001)

Perhaps

Would

Seem

Largely

Partly

Typically

Might

Occasional

Suspect

Somehow

Guess

It would seem

As it happens

At least in

At first sight

We might expect

Have been able

And the like

I have tried to

Been able to show

As might be expected

Would seem to be

As far as I am /can

Turn(s) out to be

A fair amount of

It turns out that

At the time of writing

150

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

But Swales never demonstrates, proves or establishes, and only rarely finds or shows.

Instead, his categorical assertions are more usually accompanied by an evaluative comment to convey the strength of a conviction.

Instances of ascribed ‘attitude’ in academic texts usually concern writers’ judgements of

epistemic probability and estimations of value, with affective meanings generally less

prominent (Hyland, 2000). In Martin’s (2000) terms attitudes lean towards appreciation,

or ethical evaluation, rather than affect, which expresses feelings, or judgement, concerning

moral estimations. In the Swales corpus, important, complex, useful and interesting all have

high frequencies, but the items which most distinguish his work from the larger reference

corpus are shown in Table 4.

In this list we see a range of items which can function to convey an appreciation of

social or semiotic phenomena. These are generally positive attributes and are often used

to generously evaluate the research or working practices of others, as in these examples:

(7) Certainly, I find it remarkable that even as proficient a non-native user as Yao

should have introduced such an unexpected, subtle and self-evaluative question

about her writing into the discussion.

(2001b)

I see English for Academic Purposes as an established ESL specialisation of proven

worth, resourced by dedicated career professionals of considerable technical competence. . .

(1994)

For this, I will use Anne Beaufort’s excellent but insufficiently known 1998 volume

entitled ‘Writing in the Real World’.

(2002b)

..from Hyland’s (2000) rich account of disciplinary discourse in eight fields. (2004a)

Equally, however, Swales uses these markers of attitude to stress strongly felt commitments to a particular viewpoint, typically concerning text features or research results, as in

these cases:

(8) One of the surprising features of Huddleston’s corpus is the rarity of the -ing

complementizer. . .

(2004c)

Some of the most dramatic findings are the self-reports elicited by Jernudd & Baldauf, (1987) from Scandinavian psychologists.

(2004c)

Some shift in the reading research area towards a genre perspective would seem

highly desirable.

(1990)

Certainly, accumulations of such incidental findings provide little in the way of a

platform from which to launch corpus-based pedagogical enterprises

(2001b)

As can be seen from several of these examples, Swales uses boosters to graduate his

expression of attitude (most, highly), what Martin (2000) refers to as ‘turning up the volume’ in order to emphasize the force of his convictions.

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

151

Table 4

Keywords expressing attitude (p < 0.0000001)

scholarly

technical

literary

contemporary

rich

intellectual

best

highly

new

impressive

interesting

unusual

original

exceptional

excellent

valuable

standard

extensive

hard

strong

useful

complex

uncommon

relevant

Through these acts of personal involvement and professional investment we are invited

to share his understandings and subscribe to his take on the ways that both people and

language behave. This is not to say that Swales’ arguments are never anything but fully

researched and amply supported by empirical evidence and careful logic. But this is not

all there is to it. By scattering expressions of attitude through his texts Swales creates

for himself a distinctive discoursal style and adds another rhetorical string to his bow.

He shows what he thinks about matters and not just what the data tells us; he aligns himself with a viewpoint in a very personal way and sucks us into the argument through the

force of his commitments so that we get a sense of participating in an unfolding exploration of the issues.

2.3. Reader engagement

In addition to a clear, and very personal, authorial stance expressed through reflection, self mention, hedging and attitude markers, we have also seen that Swales works

hard to engage readers with his ideas through his writing. Successful interactions not

only involve a writer’s projection of a competent and appropriately authoritative stance,

but must also recognise and respond to the potential objections, misunderstandings and

processing difficulties of readers. In this regard, Swales always treats his audience with

respect and consideration. He weaves his texts as a kind of collusive web to construct

a professional context in which we are always seen as intelligent colleagues sensible

enough to follow what he has to say. As I noted earlier, his arguments and claims

are often softened to represent an open-minded persona and to accommodate readers,

but he frequently goes further to meet our expectations of inclusion and anticipate

our questions and perspectives, drawing us into a shared experience of some interesting

finding or puzzling data.

One aspect of this, and a relatively unusual one in my experience of studying academic prose, is a slightly quaint and dated reference to ‘the reader’. There are 16 mentions of the reader in the Swales data compared with just four in a corpus of 240

research articles of 1.4 million words: about 160 times more uses. Eighteenth and nineteenth century novelists would often use the words ‘gentle reader’ to self-consciously

remind their audience that the text had been written by somebody who wished to guide

them and share their experience of reading. For Swales, the device seems to perform a

similar useful purpose. He often resorts to it to explicitly bring readers into the discourse

at certain points, reminding them that they are linked by a common curiosity and

engaged in the same fascinating endeavour. It is a strategy which has the effect of

152

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

projecting a sympathetic, good humoured and almost avuncular, tone to the discourse.

But while this may be the case, it is also something of a wolf in sheep’s clothing as it is a

device for leading readers along, putting thoughts, and even words, into their minds to

bring them to the writer’s view. These cases are typical:

(9) As the reader can see, there has been a determined effort here to communicate

appreciation for the work involved, all six invoking the. . .

(2004a)

I dare say that the reader has already noticed that the activity itself provides a basis

for the group writing. . .

(1990)

By now, the question may have arisen in the reader’s mind ‘‘well, if the typical dissertation (apart from those in strict article-compilation format) is not so much like a

much expanded research article, is it then like an academic monograph?’’ (2004a)

I wince, doubtless like the reader, at the unfortunate sequence of metaphors in the

last two sentences.

(1998a)

Now, I can hear the reader thinking ‘‘Surely we can solve this problem by having

the same teacher teach two matched groups of learners using two different

methods’’.

(1993)

A more conventional, and obvious, way of engaging readers is through the use of inclusive we. Binding readers to the writer is a common feature of persuasive prose and readerinclusive we is the most frequent engagement device in academic writing (Hyland, 2005b).

It is, however, particularly salient in the Swales’ corpus where it is among the top 50 keywords (significant to over 10 decimal places by the log likelihood statistic). As might be

expected, the majority of these uses in the Swales’ corpus are associated with primary auxiliaries (have, are, do) and modals (can, might, need, may, could), but beyond these we can

observe the considerable interactivity of this pronoun in the corpus by noting the most frequent main verbs it combines with. Table 5 lists these main verbs together with their frequencies for up to three words to the right of the keyword.

It is not surprising to find the cognition (or ‘mental’) verbs see, find and know at the

head of the list as these are common in academic writing (Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad, & Finegan, 1999) and in linguistics in particular (Flottum, Kinn, & Dahl, 2006).

These verbs, when associated with inclusive we, help recruit the reader into the interpretation process by assigning them a researcher role, guiding readers through an argument and

Table 5

Main verbs (lemmas) collocated with we in the Swales corpus

see

need

find

know

recognise

201

61

60

54

25

expect

note

use

take

look

24

22

22

16

15

go

want

seem

examine

learn

14

12

12

10

10

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

153

towards a preferred reading of the evidence. Typical examples from the corpus show how

this interactive feature often shades into explicit positioning of the reader

(10) As we have seen, in research papers experimental data tend to be given chronological as well as logical priority.

(1990)

And the result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities

overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities, sometimes similarities

of detail.

(1990)

I think we know in our hearts that the real issues are about how ESP operations are

perceived in the wider administrative and operational environment.

(1994)

. . .. . .overall we seem, at least in research and scholarship, to be approaching a situation in which English is becoming a genuine lingua franca.

(2004a)

There is then, in this use of we, an attempt to build a relationship through an implicit

claiming of solidarity with readers. Swales solicits our agreement by establishing a dialogue which simultaneously expresses an apparently reasonable point of view to anyone

who has come this far with the argument, and which seeks to head off any misgivings

we may harbour about having done so. There is also among these verbs, however, a more

direct attempt to position readers and lead them along with the argument. By the use of

obligation modals addressed to the reader, Swales presents a more assertive face, intervening to explicitly direct us to a particular understanding, as in these examples:

(11) We can salvage something of our hopes. First, we need to go back and review

what we mean by discoursal competence. Here we need to recognise both the difference between and the relationship between conversation management and oral genre

skills.

(1993)

We now need to know more about how sociolinguistic and sociorhetorical threats

and opportunities play out.

(1996a)

I now believe that we should see our attempts to characterize genres as being essentially a metaphorical endeavor.

(2004a)

I have elsewhere linked these forms to one of John’s own research interests, that of

imperatives, to emphasise a common directive function (Hyland, 2002a). The corpus suggests however that John is reluctant to employ such forceful and potentially risky strategies,

preferring to finesse his readers rather than bludgeon them with instructions. Imperatives

do occur in the corpus, of course, but these are often ‘textual directives’, pointing readers

to another part of the text or to another text entirely, an altogether far less threatening strategy than telling them how they should interpret an argument.

We also find John using directives for another, more metatextual purpose: bringing us

into the discussion to focus our attention on the issues he considers important and to

navigate us through his exposition. There is a particular fondness for ‘consider’, which

occurs 29 times as an imperative in the corpus, but apart from a few examples of

154

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

‘compare’(6), this is as far as he is prepared to in directing readers through his thinking.

Common imperatives either do not occur at all, or are framed by a softening device which

either dilutes or removes the directive force of the utterance. Typically this is the less

imposing ‘let us’, often accompanied by a mitigating ‘so’ or ‘now’, which has the effect

of transforming an instruction into an invitation:

(12) Now let’s look at the ‘‘of phrase’’ situation in more detail, if only because it is

the commonest structure.

(2001b)

So let us consider a few other verbs that have the potential of taking this structure.

(2004c)

Let us assume for the sake of my argument that this model covers all possible contingencies for question-following verbal behavior.

(2002b)

More usually, however, John’s preference in this guiding role is for a modalised preface

with inclusive we as subject. As can be seen from the next set of examples, the sense of tentativeness and possibility which the modal imparts to the bare infinitive considerably mitigates the imposition of a simple imperative, particularly when the reader is roped into the

idea with the ubiquitous we:

(13) It might be helpful at this juncture to consider a simple hypothetical situation

. . ..

(2002b)

Finally, we might note that in neither Move 2 nor Move 3 are there any of those

positive evaluations that seem to be increasing in contemporary research paper introductions.

(2004a)

We may recall the case of Hsin/Gene.

(1990)

We could look in a little more detail at the verb associate since it has the highest frequency of passives.

(2004c)

Here, once again, we see John deploying linguistic resources which allow him to present

his arguments with courtesy and consideration for the reader, while not compromising

either the clarity of his presentation or the strength of his convictions.

2.4. Reader considerateness

A final category of expressions notable for their frequency in Swales’ writing are those

which carry interactive metadiscourse meanings, considering the reader’s processing of the

text rather than their engagement with its content.

Metadiscourse refers to the interpersonal resources used to organise a discourse or the

writer’s stance towards either its content or audience, shaping arguments to the needs

and expectations of a particular community of readers (Hyland, 2005; Hyland and

Tse, 2004). While metadiscourse is not always defined in the same way, it is a useful

umbrella term for collecting together an heterogeneous array of interpersonal features

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

155

Table 6

Interactive metadiscourse signals in the corpus (p < 0.00000)

So

in terms of

as opposed to

Final

Last

First

Since

at this juncture

as we have

as it happens

and the like

we have already seen

we can see that

despite * to the contrary

in * section

of language use with broadly similar rhetorical functions. These can be grouped into two

areas: interactional and interactive, reflecting two sides of the interpersonal metafunction

of language (Hyland, 2005). The former concern many of the features discussed above to

impart an interpersonal tenor to a piece of writing: signalling the level of personality a

writer invests in a text though self mention, hedges, attitude and the markers of reader

involvement. Interactive resources, on the other hand, refer to features which set out an

argument. Sometimes called ‘metatext’ (Bunton, 1999) or ‘text reflexivity’ (Mauranen,

1993), they are concerned with the writer’s awareness of text and ways of organising discourse to assist readers to connect, organise and interpret material in a way preferred by

the writer and with regard to the understandings and values of a particular discourse

community.

The keywords lists show several words and expressions which reveal the attention John

gives to monitoring his evolving text to make it coherent for readers (Table 6). Interactive

metadiscourse signals refer to a number of such functions, including the ways writers mark

steps in the discourse, announce their goals and shifts of topic, restate claims and refer to

other parts of the text to make relevant material salient to the reader in recovering the writer’s intentions. Table 6 lists the most prominent features of this kind in the corpus. These

features include final, first and last which sequence steps in an argument; in the next section

which structures text stages; and in terms of which specifies constraints on the interpretation or applicability of a statement.

Most commonly, however, John is particularly concerned with assessing what needs to

be made explicit by frequently comparing and summarizing material as he goes along. Significant groupings of interactive metadiscourse items in the Swales corpus are used to

express contrast, inference and result, and to summarize material.

John often makes use of arguments which present ideas as contrasts or comparisons. At

the same time, for example, occurs 22 times in the corpus and on the one hand (always with

the article) 41 times. Interestingly, on the other (hand) occurs over three times as often (129

occurrences). This construction is sometimes employed to smuggle a preferred interpretation into an argument with a sleight of hand, but in Swales’ work it typically represents a

genuine recognition of complex and often puzzling realities:

(14) More precisely, would we do better to interpret such differences as deriving principally from, on the one hand, an Islamicized verbalistic tradition and, on the other,

a secularized pragmatic European or North American tradition?

(1990)

On the one hand, in most classes critical discussion tends to focus on scholarly books

and research articles. On the other, most Masters programs have a course that deals

with the analysis and use of published teaching materials.

(2004b)

156

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

More usually, however, we find options presented as oppositions which might, by more

stylistically less fastidious writers, be linked in other ways, perhaps with a simple conjunction, or even framed as a different relation altogether. In many cases oppositions could

equally be seen as additive or even sequential and that it is a rhetorical contrast which

is being constructed, rather than a real world one:

(15) On the one hand, they are typically formal documents which remain on file; on

the other, they are rarely part of the public record.

(1996a)

On the one hand, there is growing acceptance that it is intuition-rather than database

manipulation per se which underpins successful exploration of a corpus; on the

other, in my own experience there seems to be a larger amount of trial-and-error

involved than in more traditional approaches.

(2004a)

On the one hand, requesters may feel that a grateful acknowledgement of compliance

will enhance the chances of a positive response. Secondly, the ‘thanks’ statement

occurs on Reprint Requests because of the essentially ‘one-shot’ nature of the communicative event.

(1990)

John’s rare lapse in the last example here, for instance, blurs the connection between the

two ‘hands’ and suggests another way of seeing the connection.

A second grouping of items clusters around the expression of inferences about results or

observations. Interpretations seeking to explain why things are as they are or why certain

decisions were made are obviously central to academic writing and figure massively in

Swales’ discourse. These functions can be expressed in numerous ways, mainly by adverbials and prepositional phrases, and in the corpus, for instance, we find 362 occurrences of

because, 57 of in consequence, 38 of a * reason (38), 24 as a result of, and 22 due to. These

demonstrate the care with which John ensures readers are able to recover the outcomes of

his argument:

(16) There is a final reason, however, for giving prominence to the RA: the RA has a

dynamic relationship with all the other public research-process genres.

(1990)

However, this trend may be partly due to the fact that the Physical Review uses a

numerical/superscript system. Such systems do not easily permit Integral reporting

choices.

(1990)

These two intellectual worlds thus continue to be socially constructed poles apart,

perhaps because SLA continues to focus on grammar and its acquisition by young

and often beginning learners.

(2000)

Spelling out reasons for research decisions or real-world phenomenon in this way, usually with a characteristic sprinkling of appropriate caution and mitigation, both reveals

something of how he assesses his audience and their knowledge, and a desire for his reasoning to be as transparent as possible to them.

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

157

Finally, there is a strong tendency for regular highlighting and summarizing of the

argument in John’s writing, with an overwhelming preference for overall (40 clause initial

occurrences), as we have seen (38 occurrences) and we have * seen (21).

(17) Overall, I therefore believe that my way of proceeding has been set up not to

predispose or prejudge the existence of discourse communities, but if anything to

presume the opposite.

(1996a)

As we have seen, the author of this text opted for a composite ’chunked’ 1-Step 3

followed by a composite Move 2.

(1990)

All in all, commodification seems at best a partial, and perhaps even a reversible,

trend.

(1996a)

We have already seen that they vary according to complexity of rhetorical purpose from the ostensibly simple recipe to the ostensibly complex political speech. (1990)

This regular reviewing of outcomes, and the care in labelling them as such, illustrates

once again John’s metadiscoursal concern for framing his discussion with readers in mind.

An interesting, and quirky, variation on this regular gisting of material is John’s use of

introductory prefaces like it turns out that (14 occurrences) and as it happens (20) which cataphorically alert the reader to events and findings which do not necessarily follow from the

preceding discourse or which might be considered somehow unexpected or counter-intuitive:

(18) Thus it turns out that certain legal, academic and literary texts all point to

another kind of contract that can exist between writer and reader.

(1990)

So it turns out that the crash-safety experts are highly urbanized, while the systematic biologists, remain surprisingly rural. . .

(2004a)

As it happens, Knorr-Cetina’s informants - as well as numerous others - deny that

replication is really possible.

(1990)

As it happens, I have long thought (and argued) that it is methodologically unjustified to pre-select for the discourse analysis of academic texts or transcripts only those

exemplars which have apparently been written or spoken by ‘‘native speakers’’ of

English.

(2004a)

These expressions, it seems to me, are quintessentially Swalesian in that they not only

help readers to navigate the discussion, but they do so by lending a strong interpersonal

element to it. They inject an attitude of conviviality into the text as Swales shares a certain

surprise or even amused astonishment with readers at the unfailingly interesting nature of

rhetorical and human behaviour. Here is John, once again, not just informing us of his

findings and reflections, but leading us on a shared journey of exploration into the wonders of academic discourse. We see once more that his rhetoric, as much as his ideas, is

informed by a strong sense of social engagement.

158

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

3. A conclusion: individuality and disciplinarity

This has been a strange article for me to write. I have tried to look at the writing of just

one academic and characterise what is distinctive about Swales’ use of language as

opposed to what is interesting about his ideas. I have only been able to look at a small

part of his output, but have tried to characterize his rhetorical style through corpus analysis techniques and a personal proclivity for the ways academics present themselves and

their readers in their texts. I have also tried, through my own impressions and an abundance of examples, to give a flavour of some of the ways that John approaches the ideas

for which he has become deservedly famous.

The question arises, of course, of how important any of this actually is. Do language

choices make any kind of difference to how we understand an argument and whether we

are persuaded by it? How far does rhetoric maketh the scientist and to what extent can we

attribute the influence of John Swales to the ways he sets out his ideas? The answer, in individual cases such as this, is probably ‘just some’. As applied linguists we perhaps attach too

much importance to the object of our trade and John has been quick to chastise those who

suggest that rhetorical choices should be given more credence in academic success than less

tangible attributes such as networking, contacts, experience, craft skills, individual ability,

or even long hours spent pouring over concordance lines. My own social constructionist

excesses have been admonished by an anonymous reviewer on several occasions, in a distinctive prose style which reveals the identity behind the words.

But while individual brilliance will doubtless always shine through, it is equally the case

that we are ultimately defined and judged by our writing. There is an essential and integral

connection between the nature of knowledge and the cultures of disciplinary groups which

is mediated by distinctive patterns of language so that, to put it crudely and no doubt a

shade polemically: we are what we write. An engineer is an engineer because he or she

communicates like one and the same is true for biologists, historians and applied linguists.

In so far as there has been anything which can be graced with the description of ‘argument’

in this paper, it has been that we select our language to take positions, engage with readers

and convey our research with a potential audience in mind.

John’s writing, however, shows that we are not automatons blindly following the dictates

of disciplinary socialisation or the prescriptions of style manuals. The creation of an authorial

persona is clearly also an act of personal choice, where the influence of individual personality,

confidence, experience, and ideological preference all enter the mix to influence our style. The

distinctiveness of John’s voice reveals both the breadth of the options that are acceptable to

community members and the freedom of established disciplinary celebrities to manipulate

them. The fact that John’s personality comes through so strongly in his writing, however,

might also suggest a decision to emphasise an individual persona over a collective ethos as

it hints at, and constructs, an interdisciplinary diversity in the ways that knowledge is argued

and negotiated in EAP. In some ways John’s prose style recalls other ways of talking about

knowledge which perhaps tempers the influences of the empirical social sciences with the

more reflective traditions of the humanities as he introduces us to the ideas he has encountered and reshaped from thinkers who do not fit neatly into our discipline.

But writers do not construct self-representations from an infinite range of possibilities.

While they are able to control the personal and cultural identity they are projecting in their

writing, they do so by using the cultural resources their communities make available to

them. Knowledge is largely constructed within particular communities of practice and

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

159

these communities exist in virtue of a shared set of assumptions and routines about how to

collectively deal with and represent their experiences. While John may wear his heart on

his sleeve more than most with a personally committed and engaging style, he is not writing in a social vacuum. His disciplinary voice is ultimately achieved by a shrewd assessment of his readers and their socially determined and approved beliefs and value

positions. Although he encourages us to see what he sees in his own way, his independent

creativity is ultimately shaped by an accountability to shared practices. He just does it

better than most of us.

Appendix. The Swales’ corpus

1990 Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research.

1993 Communicative language teaching and the need for discourse structure, In Proceedings of the MATE conference, Morocco.

1994 ESP in and for human resource development. ESP Malaysia, 2: 1–18.

1995a The role of the textbook in EAP writing research. English for Specific Purposes,

14: 3–18.

1995b Field guides in strange tongues: A workshop for Henry Widdowson. In G. Cook

& B. Seidelhofer (Eds) Principles and practice in the study of language: Studies in

honour of H.G. Widdowson; Oxford University Press (pp. 215–228).

1996a Occluded genres in the academy: The case of the submission letter. In E. Ventola

& A. Mauranen (Eds.) Academic.

1996b Teaching the Conference Abstract. In E. Ventola & A. Mauranen (Eds). Academic Writing Today and Tomorrow. University of Helsinki Press: Helsinki

(pp. 45–59).

1998a Other Floors, Other Voices: A Textography of a small University Building. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

1998b Language, Science and Scholarship. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching,

8: 1–18.

2000 Languages for specific purposes Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 20: 59–76.

2001a Metatalk in American academic talk: The cases of ‘‘point’’ and ‘‘thing’’. Journal

of English Linguistics, 29:34–54.

2001b Integrated and fragmented worlds: EAP materials and corpus linguistics. In J.

Flowerdew (Ed.) Academic Discourse. (pp. 153–167) London: Longman.

2002a Issues of genre: Purposes, parodies, pedagogies. In A. Moreno & V. Colwell

(Eds.). Recent perspectives on Discourse (pp. 11–26). AESLA: The University

of Leon Press.

2002b On models in applied discourse analysis. In C. Candlin (Ed.) Research on Discourse and the Professions. (pp. 61–77). Hong Kong: City University Press.

2004a Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge University Press.

2004b Evolution in the discourse of art criticism: The case of Thomas Eakins. In H.

Backlund et al. (Eds.) Text i arbete/Text at work. (pp. 358–365). Uppsala,

Sweden: The Institute for Nordic Languages.

2004c Then and now: A reconsideration of the first corpus of scientific English. Iberica

8: 5–22.

160

K. Hyland / English for Specific Purposes 27 (2008) 143–160

References

Biber, D., & Finegan, E. (1989). Styles of stance in English: lexical and grammatical marking of evidentiality and

affect. Text, 9(1), 93–124.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written

English. Harlow: Longman.

Bunton, D. (1999). The use of higher level metatext in PhD theses. English for Specific Purposes, 18, S41–S56.

Flottum Kinn & Dahl (2006). ‘We now report on ...’ Versus ‘Let us now see how ...’: Author roles and interaction

with readers in research articles. In K. Hyland & M. Bondi (Eds.), Academic discourse across disciplines

(pp. 203–233). Frankfort: Peter Lang.

Hyland, K. (1998). Hedging in scientific research articles. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hyland, K. (2000). Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. London: Longman.

Hyland, K. (2001). Humble servants of the discipline? Self-mention in research articles. English for Specific

Purposes., 20(3), 207–226.

Hyland, Ken. (2002a). Directives: power and engagement in academic writing. Applied Linguistics, 23(2),

215–239.

Hyland, K. (2005a). Metadiscourse. London: Continuum.

Hyland, K. (2005b). Stance and engagement: a model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Studies,

7(2), 173–191.

Hyland, K., & Tse, P. (2004). Metadiscourse in academic writing: a reappraisal. Applied Linguistics, 25(2),

156–177.

Martin, J. (2000). Beyond exchange APPRAISAL systems in English. In S. Hunston & G. Thompson (Eds.),

Evaluation in text authorial stance and the construction of discourse (pp. 142–175). Oxford: OUP.

Mauranen, A. (1993). Contrastive ESP rhetoric: Metatext in Finnish–English Economics texts. English for

Specific Purposes, 12, 3–22.

Scott, M. (1998). Wordsmith tools 4. Oxford University Press.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: CUP.

Swales, J. (1998). Other floors, other voices: A textography of a small university building. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Swales, J. (2004). Research genres. New York: CUP.

Ken Hyland is Professor of Education and director of the Centre for Academic and Professional Literacies at the

Institute of Education, University of London. He has been teaching for 28 years and published over 120 articles

and 11 books on language teaching and academic writing. Recent publications include Teaching and researching

Writing (Longman, 2002), ‘Second Language Writing’ (Cambridge University Press, 2003), Genre and second

language writing(University of Michigan Press, 2004), Metadiscourse (Continuum, 2005) and EAP an advanced

resource book (Routledge, 2006). He is co-editor of the Journal of English for Academic Purposes.