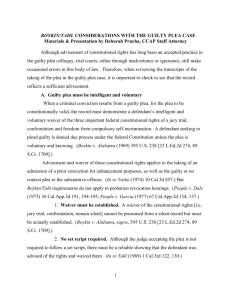

Innocence Effect

advertisement