Special Issues for Prisoners with Mental Illness

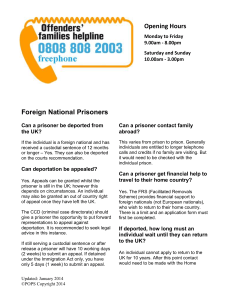

advertisement