Charles Chesnutt's The Conjure Woman

advertisement

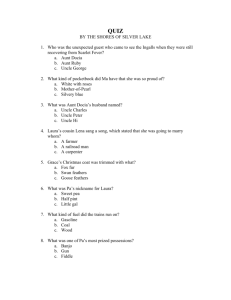

Charles Chesnutt's The Conjure Woman Stephen Yenik At first glance, the stories in Charles Chesnutt's The Conjure Woman seem similar to Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus tales, but a careful reading reveals that, while similar in form and the use of the slave dialect, they are in fact quite different in both intent and literary quality. Harris was motivated by a misguided nostalgia. Modern reading and analysis of the tales has exposed the double meaning of the tales and how they were used to instruct the children of slaves in ways to make the best of their miserable situation through the use of wit and guile. This subtle aspect of slave culture, however, was as opaque to Harris as it was to the masters in the days of slavery. As he states in the introduction," ... my purpose has been to preserve the legends themselves in their original simplicity, and to wed them permanently to the quaint dialect-if, indeed, it can be called a dialect-through the medium of which they have become a part of the domestic history of every Southern family; and I have endeavored to give to the whole a genuine flavor of the old plantation." In other words, Harris was an unreconstructed, nostalgic Southerner who looked back at the days of slavery with fondness. Charles Chesnutt's purpose was the opposite of Chandler's. Writing during the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the concerted attempt of white Southerners to roll back all the advances the freedmen had made during Reconstruction, Chesnutt's aim was to remind people of the crime of slavery and put a stop to the growth and spread of the new version of history being promoted by both Southern and Northern whites. Of course, he also realized the urgent need to expose the criminal behavior (lynchings, burnings, beatings denial of rights etc.) in the post-bellum South. whole had lost The problem he confronted was that the country as a the Charles capacity to contemplate the horrors of slavery or to empathize with the struggles of the recently freed blacks. Most people were anx1ous to forget the bitterness of the war and were willing victims of a fictionalized Waddell Chesnutt (1858- 1932), Afro-American writer known for his novels and stories dealing with racial problems following the Civil War. After the disappointment and failure of Reconstruction, Chesnutt used his rich experience living in both the North and the South to create dynamic novels and stories exploring the race question. His major works include the short story collections, The Conjure Woman and The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line, and the novels, The House Behind the Cedars, The Marrow of1}adition and The Colonel's Dream. -18- history of the good old plantation days. Chesnutt's first step was to establish himself as a writer without engendering any bitter controversies. Reasoning that he could produce serious and explicit works attacking racism once he was accepted as a writer of merit and ability, he threw his hat in the ring with his Conjure Woman stories. This plan succeeded admirably. Casual readers enjoyed the stories as a sort of light entertainment, but for the more discerning reader, Chesnutt cleverly wove in his own subversive message. Chesnutt chose to use the form of a story within a story, another superficial resemblance to Harris's Uncle Remus tales. Uncle Remus is an old ex-slave who entertains a little white boy with folk tales so that each tale is framed by some brief interaction between the two: The little boy comes to Uncle Remus and asks for a story. Uncle Remus tells the tale, which constitutes the main part of the story. At the end of the tale, there is another exchange between the boy and Uncle Remus. Although Chesnutt uses the same basic form, it is more elaborate. The role of the little boy is taken by a Northern white man and his wife, "John and Annie." They have immigrated to North Carolina and taken up farming after being advised that the climate might prove beneficial for the wife who suffers from poor health. Uncle Remus becomes Uncle Julius, an old, ex-slave born and raised on the plantation the white man purchases. John employs Uncle Julius as a farm hand. He finds Uncle Julius's local knowledge useful, and they both find his stories of the bygone days of slavery entertaining. Uncle Julius's stories differ from the animal tales of Uncle Remus in a number of ways. First of all they are not presented as amusing stories for pure entertainment but as actual events that really happened. Uncle Julius, of course, knows that white folks would never admit that there is any truth to his weird tales of conjuring and witchcraft, that they will listen with a condescending smirk. But he is also a practical psychologist and a past master at manipulating white folk while keeping up a facade of subservience and simplemindedness. John, his new employer, makes an inviting mark, being from the North and having a more broad-minded and generous spirit than could be expected of the local white population. John's wife Annie is an even more inviting target: Uncle Julius homes right in on her emotional sensitivity and susceptibility. For example, John tells Julius he plans to tear down an old, unused school house on his property and use the lumber to make a new kitchen. This runs directly counter to Julius's plans, but he doesn't make any immediate or obvious objection. He bides his time and finally sees his opportunity on a trip to the local sawmill with John and Annie in order to have some additional new lumber sawn for the new kitchen. He begins to look and act sad and mournful, and when John asks him if something is wrong, he says nothing much except that the sound of the saws ripping through the log has reminded him of "po' Sandy". -19- John and Annie ask to hear the tale, of course, and Uncle Julius gladly tells it. Sandy had been a sort of super slave, strong, willing and skillful, but this only increased his burdens; his master was constantly loaning him out to friends and relatives on other plantations. One day, before setting out on what would be another long separation from his beloved wife, he bemoans his fate and wishes he could just stay in one place for a while. His wife reveals her secret conjuring ability and suggests she change him into an animal so that they can stay near each other. Finally they decide on a large pine tree rather than an animal, and Sandy's wife secretly visits him at night when she temporarily changes him back into a man again. This goes on for sometime. Sandy's master thinks he has simply run away, and Sandy and his wife are considering when it might be safe for them to finally escape together. An unfortunate train of circumstances results in Sandy being sawn up for lumber to make a new kitchen. His wife loses her mind with grief, and it proves to be impossible to get the slaves to work in the new kitchen as it is haunted. The clincher is that the new kitchen was eventually torn down and the lumber used to build the old schoolhouse that John plans to tear down for Annie's new kitchen. The next day Annie asks John to build her new kitchen with all new lumber. She doesn't admit to believing in ghosts or anything but nevertheless Julius has told the tale well enough that she would always associate the new kitchen with Po' Sandy, and John has to foot the bill for all the new lumber. This is a tribute to Julius's story telling power: to make the unbelievable effective in a real and practical way. Julius's devious plan comes to light about a week or so later. He asks Annie if he might not use the old school for meetings of a new church group, as ghosts never disturb religious services. Julius dos not always come out on top as he does in PoJ Sandy, but he certainly keeps John on his toes. Contrary to Harris's condescending portrayal of Uncle Remus, Chesnutt uses the story-within-a-story format to show that Uncle Julius's natural wit is not inferior to John's well-educated intellect. This can be applied to the language and poetic imagination of slave culture as well. While Harris cannot acknowledge Uncle Remus's dialect as anything but the crudest sort of speech which just barely lies within the realm of language, Uncle Julius is a master of simile, metaphor and imagery. His vivid and lively narratives never fail to caste a spell on John and Annie and more often than not cause them to alter their behavior or plans, albeit indirectly as they could never admit to being susceptible to the fantastic ramblings of an old, ignorant ex-slave. Chesnutt makes this point clearly in The Gray Wolfs Ha Jnt. Annie asks John to read to her to while away the time. -20- It's a dull day, and John obliges her with a passage from the philosophy book he has been perusing: "The difficulty of dealing with transformations so many sided as those which all existences have undergone, or are undergoing, is such as to make a complete and deductive interpretation almost hopeless. So to grasp the total process of redistribution of matter and motion .... " After a few more lines of this, Annie petulantly interrupts John saying, "I wish you would stop reading that nonsense and see who that is coming up the lane." Uncle Julius soon arrives and vanquishes Annie's tedium with his narrative magic. As John Edgar Wideman points out in his essay Charles Chesnutt and the WPA Narratives: The Oral and Literate Roots ofAfro-American Literature, the black dialect had always been used to poke fun at the slaves and to demonstrate their irredeemable inferiority. Chesnutt, however, had both a solid, traditional classical education and a long and close association with the ex-slaves of his native North Carolina, and thus he was able to artfully present the slave dialect as different but not deficient, as having its own intrinsic poetic value. Obviously the story teller's first aim must be to get his listeners full attention. Here is how Uncle Julius makes his opening bid in Po' Sandy as he, John and Annie watch the great saw tear through a log: "Ugh! But dat des do cuddle my blood!" "What's the matter, Uncle Julius?" inquired my wife, who is of a very sympathetic turn of mind. "Does the noise affect your nerves?" "No, Mis' Anne," replied the old man with emotion, "I ain' narvous; but dat saw, a-cuttin' en grindin' thoo, dat stick er timber, en moanin', en groanin', en sweekin', kyars my 'memb'ance back ter ole times, en 'min's me er po' Sandy." Chesnutt, aware that the printed word can never carry the full meaning of the spoken word, notes that Julius spoke in a "lugubrious tone" and that he "lengthened out 'po' Sandy"' with a "pathetic intonation." Reading passages out loud brings out the importance and richness of the tone and rhythm of the language. (No matter that the reader utterly fails to make even a fair approximation of the original, just trying is enough.) Chesnutt is working in an area where the oral tradition recovers its original strength and meaning, where language is not an elaborate code of visual symbols but an event or "happening", and where the sound is the meaning in an almost musical sense. Ulysses S. Grant has gotten a bad rap for his performance as the President of the United States (1869-1877). He is portrayed as being muddled and effectual. Popular history also claims that, while he himself was scrupulously honest, he allowed his corrupt cronies to run amuck. This is just one example of the way history was "revised" in the late 1800s to suit Southern "sensibilities." Furthermore Reconstruction policies were, and still -21- are in some cases, seen as the instruments of punishment wielded by fanatically vindictive and mean Northerners as well as the vehicles for selfish enrichment by corrupt scalawags and carpetbaggers. The purpose of this distortion of history was to allow Southern whites to regain political and economic control of the South and reestablish their superior social status. At the end of the war, the South's economy was in tatters, and the only things left to the old guard were pride and their land. But the land could not produce any profit without labor and so the former slave masters went about finding ways to keep the newly freed slaves working and in a markedly subservient position; in short, to put and hold them in a system of peonage which differed very little from slavery except that they were no longer able to actually buy and sell human chattel. To accomplish this they became terrorists. Forming secret societies of which the Ku Klux Klan is the most notorious, they forced the black population into submission by subjecting them to beatings, burnings, and lynchings. Grant's crime was not turning a blind eye to this as had his predecessor Andrew Johnson. His vigorous opposition to this criminal behavior included signing the Enforcement Act to protect blacks' right to vote, which had just recently been established by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and sending Federal troops to various trouble spots where illegal combinations or the Ku Klux Klan were active. Gradually his policies lost popularity in the North, not to mention the South, due to a combination of racism and apathy. The people evidently did not see any reason to trouble with the rights of those who were so clearly inferior. The unpopularity of his policies did not deter Grant, however, and in his Sixth Annual Message he said, "While I remain Executive all the laws of Congress and the provisions of the Constitution ... will be enforced with rigor ... Treat the negro as a citizen and a voter, as he is and must remain ... Then we shall have no complaint of sectional interference." He also signed the Civil Rights Act on March 1, 1875, which prohibited racial segregation in public accommodations, transportation and jury selection and was the most thorough piece of civil rights legislation passed until 1964, nearly 100 years later.. The Hayes-Tilden presidential election was the death knell for Reconstruction and ended the Federal Governments efforts to protect the rights of the freedmen. The dispute surrounding the election was overcome by a backdoor deal whereby Hayes was confirmed as President in exchange for assurances that he would abandon Grant's Reconstruction policies. With the Federal Government out of the picture, the Ku Klux Klan and people with an identical viewpoint inexorably ground away the freedmen's social and economic standing, denying them the right to vote, shutting them out of all except the most menial -22- economic activity, and restricting them to utterly inadequate educational opportunities. In 1883, the Supreme Court ruled that Grant's civil rights legislation was unconstitutional, and this set the stage for the final onslaught, allowing the South to disenfranchise the black population and establish an apartheid system of peonage. Charles Chesnutt threw his hat into the literary ring in 1887, and in that same year published the Goophered Grapevine, the first of the conjure woman stories, in the August issue of the Atlantic monthly. This was not a step taken lightly. Entries in his journal from 1880 show that he had already thought the matter out carefully and had a well developed literary strategy. Judge Tourgee' s novel A Fool's Errand, an examination and analysis of the race problem in the South, had just been published and met with considerable success. Chesnutt reasoned that his background and training qualified him to outdo Tourgee's success: ... And if Judge Tourgee, with his necessarily limited intercourse with colored people, and with his limited stay in the South, can write such interesting descriptions, such vivid pictures of Southern life and character as to make himself rich and famous, why could not a colored man, who has lived among colored people all his life, who is familiar with their habits, their ruling passions, their prejudices, their whole moral and social condition, their public and private ambitions, their religious tendencies and habits;-why could not a colored man who knew all this, and who besides, had possessed such opportunities for observation and conversation with the better class of white men in the South as to understand their modes of thinking; who was familiar with the political history of the country, and especially with all the phases of the slavery question;-why could not such a man, if he possessed the same ability, write a far better book about the South than Judge Tourgee or Mrs. Stowe has written? Furthermore, he realized that military and legal force could only go so far in establishing racial equality: " ... the subtle almost indefinable feeling of repulsion toward the negro, which is common to most Americans ... cannot be stormed and taken by assault; .... " He considered literature as a medium that could be used "to accustom the public mind to the idea [of social recognition and equality for Afro-americans]; and while amusing them to lead them on imperceptibly, unconsciously step by step to the desired state of feeling." One way Chesnutt used Uncle Julius was to remind the reader what slavery had been really like. By 1887 apologists for the Old South had succeeded in repainting the picture of slavery in rosy, nostalgic tones: The Old Plantation had been a paradise. A benign and paternalistic Master assiduously looked after his "servants", who, after all, were too child-like to look after themselves, and the slaves, in return, were devoted to Massa'. The plantation ran at a leisurely pace, peaceful and calm, a pinnacle of cultural -23- refinement and enlightened aristocratic order. The masters and slaves were bound together with deep feelings of mutual affection, just one big, happy family. Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin was fiction, just a story; the slave narratives published before the war were filled with atrocious lies and exaggerations. Uncle Julius tells a different story. He is not bitter or rancorous. He mentions inhuman conditions with such casual matter-of-factness that the less-discerning reader might not even notice it. The whims of the master had to be born like changes in the weather; there was no use in blaming anyone or anything. He does not dwell on the brutality; he mentions the punishment of forty lashes in the same tone as you might describe a mild spanking in your childhood. horrible. In a way, this makes it seem even more Instead of detailing the more grotesque and egregious cruelties, Uncle Julius's narrative is peppered with the torment of having every aspect of your life dictated by a deranged moron, a delusional alcoholic, or simply a plain fool. In Sis' Becky's Pickanniny, Becky's husband, a slave on a neighboring plantation, is sold away along with all the other property to pay off the debts his master left after his death. This was not at all unusual; plantation owners were often poor managers who carried as much debt as their collateral would allow without giving any thought to what this could mean to the slave families they left behind. What appeared to be the mourning of slaves for their deceased master was far more likely to be their anxiety at the uncertainties they faced and the probability that they would be separated forever from their families and friends and sold down the river. Nevertheless, this had to be born, and in Sister Becky's case she at least had the consolation of her pickaninny, Moses, a bright little boy who was the joy of her life. Now, as Uncle Julius tells us," Kunnel Pen'leton [Becky's master] wuz a kin' -hea'ted man, en did n' keer ter take de mammies 'way fum dey chillun w'iles de chillun wuz little." Unfortunately, Colonel Pembleton's ruling passion was horse racing, an avocation at which he was singularly unsuccessful. So some slight pangs of his conscience do not stop him from trading Becky away without her child when it is the only way he can find to acquire a champion racehorse. To save "trouble", he doesn't even tell Becky that she has been traded for a racehorse but that he is sending her to a neighboring plantation to help out for a couple of days. Chesnutt gives the story a fairy tale ending where the complex conjuring machinations of Aun' Peggy finally save the day after much tribulation. The reader has been amused and left with a happy ending but not without being instructed in the gross inhumanity of slavery. Chesnutt explores the deplorable state of race relations through the interactions of Uncle Julius, his employer, John, and John's wife Annie. -24- John is a Northern liberal and a decent, honest man, but at the same time he is an unconscious racist. Blinded by the "old Southern plantation" stereotype, he is sure of his superiority and takes a patronizing and paternalistic attitude towards Uncle Julius. His certainty in his intellectual superiority is ironically a manifestation of his utter obtuseness. Uncle Julius, on the other hand, has the white folks all sized up; he knows how to use John's self-confidence against him. His advantage is that he knows that John doesn't know him at all, that he is invisible. He is an ex-slave, a crafty and cunning master of playing the role expected from him and at the same time manipulating the powerful for his own benefit. He has a range of psychological levers and tools to choose from including white guilt, sentimentality, and subconscious belief in African sorcery. In his essay, "The Art of The Conjure Woman," Richard Baldwin discusses the issue of white guilt as it appears in Mars Jeems's Mghtmare. John fires Julius's grandson, Tom, for being a "trifling worker", and Julius tells his tale to remind him and his wife of the terrible victimization and deprivation blacks have suffered at the hands of powerful and privileged whites. He does not so much plead as demand that it is only right that blacks be given preferential treatment: Dis yer tale goes ter show dat w'te folks w' at is so ha' d en stric', en doan make no 'lowance fer po' ign' ant niggers w' at ain' had no chanst ter l' arn, is li'ble ter hab bad dreams ter say de leas', en dat dem w' at is kin' en good ter po' people is sho' ter prosper en git 'long in de worl'. John is somewhat resistant to this sort of moral arm twisting, but Annie decides to give Tom another chance. The Conjure Woman is an artful blend of ironic humor and tragic reality. Should we laugh or cry or do both at the same time? References: Charles Chesnutt-Stories, Novels, & Essays, Library ofAmerica-131, 1999 Baldwin, Richard E., "The Art of the Conjure Woman", from Critical Essays on Charles Chesnutt, G. K. Hall & Co. 1999, p 170-180 Wideman, John Edgar, "Charles Chesnutt and the WPA Narratives: The Oral and Literate Roots of Afro-American Literature", from The Slave's Narrative, ed. Charles T. Davis and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Oxford University Press, 1985, p 59-77 http://www.berea.edu/ENG/chesnutt/ http://docsouth.unc.edu/ -25-