“It's All in de Tale”: Politics of Narration in Joel Chandler

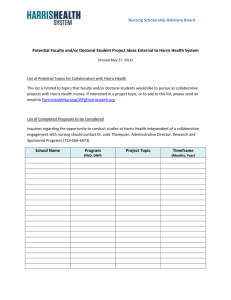

advertisement