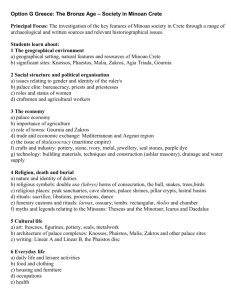

umi-umd-2478. - DRUM

advertisement