Appendix A: Helpful Things to Know

advertisement

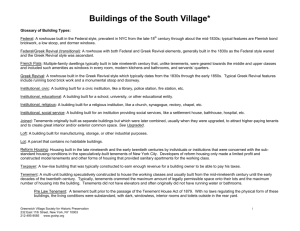

Appendix A: Helpful Things to Know As “Head Inspector” During the Interaction Janitor/Housekeeper: If there are more than 8 families living in a tenement, and the owner lives somewhere else, the Tenement Inspectors decide if there should be a janitor or housekeeper. o When the issue comes up, you can ask the inspectors in your group to decide whether or not 97 Orchard needs a janitor. Garbage Collection in 1906: The Department of Street Cleaning was responsible for collecting garbage. o As of 1896, New York City required residents to separate household waste—food waste in one tin, ash in another, and dry trash in a bag or bundle. o The garbage cans could be placed on the sidewalk. o If the inspectors are quizzing the landlord about this, you can mention that the Tenement House Department will provide receptacles for waste. An early image of the sanitation department, clad in white, collecting trash, circa late 1890s. Note the garbage cans on the sidewalk. Sinks: Each floor must have at least one sink. o This means that if the tenant is able to obtain water anywhere on his/her floor, the landlord is technically not in violation! Wallpaper: Evidence suggests that 97 Orchard’s landlords put up the wallpaper. o If the inspectors are on the tenant’s case about it, you can point out that this is a violation for the landlord to fix. 1 When Facilitating Discussion During the Wrap-Up Was it worth it to be a landlord at 97 Orchard in 1906? Barnet Goldfein purchased 97 Orchard Street with a partner, Benjamin Posner, for $20,500. Posner and Goldfein paid $8,000 to add bathrooms inside, cut through the building to create an air shaft, and install gas and water pipes. o Given that they had purchased the building for $20,500, this was a relatively huge expense. The following year, in 1907, Goldfein and Posner sold the building for $29,000. o With the $8,000 spent on improvements, their profit upon their investment in 97 Orchard was $500. If you were a tenant, how would you feel about a rent increase? Rent was around $15 a month in 1906. o It had probably been raised from something like $12, as a result of the cost of renovations. Historical Context: Rent strikes, led by activist housewives, racked the neighborhood in 1904. o In context, it makes sense that the housewives led the strikes, as they were in charge of family budgets and therefore most directly affected by the rent increases. Penalties for Non-Compliance with the Tenement House Act Landlords were given a chance to rectify found violations, and punitive action was only taken if they failed to comply. Violation was considered a misdemeanor. You could spend up to 10 days in prison for each day that a violation remained unfixed. If the offense was unintentional, you could be fined anywhere from $10-$100. If you willfully violated the law the fine could go up to $250. The amount increased by $10 for every day that the violation went unfixed. The Most Common Violations Most of the violations Tenement Inspectors found involved garbage, filth and disrepair. The Department received an average of 36,000 complaints about tenements per year in 1911 to 1912, and almost half charged a lack of cleanliness. A great deal of the work the Department accomplished involved removing garbage, cleaning, providing garbage receptacles, whitewashing, painting and miscellaneous repairs. Many of the larger tenements had a housekeeper, often a widow, who received free rent in exchange for maintaining and cleaning the halls, stairs, and sweeping the sidewalk in front of the building. 2 Historical Example In 1904, the landlord of 143 Orchard Street, Dora Reitman, was notified that she must thoroughly cleanse and whitewash/paint certain walls and remove rubbish from her tenement immediately in compliance with the Tenement House Act, or else face charges. In 1912 Dora spent $75 on plastering repairs, carpentering, and glazing, painting, papering, whitewashing, and cleaning for her tenement. Assuming that rent was approximately only $13 per month per family, these expenditures depleted her income significantly. 3 Appendix B: Tenement Inspectors Historic Overview Pre-1901 Housing Regulation in New York City Housing conditions have been a concern in New York for centuries. Early efforts to regulate housing, mostly codes about what types of building materials could be used, were limited in scope, mostly intended to prevent property loss due to widespread fire. However, as the influx of immigrants and migrants in the 19th century caused the city's population to swell, land became scarce and the poor and working class—and eventually the middle and upper-middle class—came to live in multiple-family dwellings. It became apparent to many that bad housing affected the health and safety of all New Yorkers, not just the poorest, and that government intervention was necessary. By the mid-19th century, a movement to improve housing conditions had developed. The result was the passage of the 1867 Tenement House Act, the nation’s first comprehensive housing law, which required that landlords provide a privy and a fire ladder for every 20 inhabitants, a source of water for every building and a transom window above every apartment’s sleeping room door. The reform movement continued, with successive laws raising these minimum standards, a process that has continued up to the present. Today tenements and other multiple-family dwellings must meet minimum standards, albeit standards which have changed greatly since 1867. The Reform Movement Those who suffered the most from inadequate tenement conditions were the tenants themselves. But while tenement dwellers surely had complaints about their homes and desired better-quality housing, the tenement reform movement did not begin among them. It began among middle and upper middle class New Yorkers, the city’s “prominent citizens,” merchants, ministers and physicians who formed committees, publicized tenement conditions, and pushed for legislation. o For example, the Citizens’ Association, emerging in the wake of the 1863 Draft Riots to improve tenement living conditions, was headed by wealthy industrialist Peter Cooper. By the turn of the century professional reformers, or “housers” like Lawrence Veiller, were joined by celebrity journalists like Jacob Riis, society women-turned-social workers, scientists and prominent politicians like Theodore Roosevelt. This group saw bad housing as the ultimate source of all urban ills– not just disease and fire but crime, joblessness and the breakdown of the family – and good housing as the solution to these problems. Progressives In the 1890s, the Progressive movement gained momentum with many collegeeducated, chiefly American-born, middle-class people. 4 While old ideas attributed these urban plagues to the so-called immorality of the poor, those caught up in the progressive movement placed the blame on poor conditions in neighborhoods like the LES. o “Most [Progressives] had conceded that industrial capitalism was here to stay—but how could it be made more efficient and more humane? How could government become more responsive to these social problems? How could government become less corrupt, and more efficient? Underlying the various initiatives was the belief in the importance of social cohesion and the idea that the welfare of any individual depends on the welfare of larger society as a whole.”1 Tenement reform is the perfect example of progressive ideas and methods – take a social problem – study it – problem solve – repeat. In New York, Progressives were invested in shaping the city into a modern mecca, which would serve as a shining example to the rest of the country (and the world). o This would not be possible until slums, like the Lower East Side, were transformed. Reformers’ Concerns The reformers most basic concerns were disease and fire, but there were several other considerations as well. Disease 1 Housing reform reflected changing ideas about disease, its causes, and who is responsible for preventing it. Many 19th century New Yorkers believed disease was caused by vice and immorality of the sufferer. But by the middle of the 19th century it was becoming clear to some that there was a connection between disease and environment. In particular, the epidemics that struck the city repeatedly in the 1800s dramatically illustrated the connection between disease and poor housing. o The cholera that hit the city in 1832, 1846, 1866 and 1892 struck hardest in poor neighborhoods and would subside only when these tenement neighborhoods were thinned out by the deaths. o As doctors visited the sick in unventilated, crowded buildings, even in flooded cellars, it became clear that tenement conditions and disease were connected. Today we know that the lack of sanitation and close living quarters helped germs spread quickly and easily. However, the mid-19th century reformers did not yet know what germs were. Instead, they spoke of disease-causing “miasmatic vapors,” given off by fermenting garbage, rotting food and human and animal waste. o Lack of light and ventilation as well as overcrowding were thought to increase the negative effects of these vapors. The cholera epidemic in 1866 pressed home the need to clean up the tenement districts, resulting in the passage of the Tenement House Act of 1867. Polland, Essay 5 However, when scientists discovered germs, housing reformers had to shift their argument. o By the passage of the 1901 Tenement House Act, reformers were arguing that germs caused disease and that poor light, ventilation and sanitation helped germs spread. o They even contended that germs would permanently infect a building. For this reason, the Tenement House Act of 1901 required wallpaper be removed before a new layer went up. Reformers also stirred public concern by reminding middle class consumers that many of the goods they bought were made in tenement apartments. o They effectively used media to help people understand that poor housing impacted more than just the lives of the tenants. While germ theory did not diminish the power of the reform movement, it did change it. Reformers became less moral crusaders, and more technicians or medical professionals. Fire Tenements were very vulnerable to fire. The 1867 Tenement House Act required fire escapes, but enforcement was lax. Almost 2,000 people lacked adequate fire escapes in just one Lower East Side ward, according to a 1900 Tenement House Commission study. Also, when they had no space in their apartments, tenants often kept household possessions out on the fire escapes, making them impossible to use in an emergency. Maintaining Social Order Disease and fire was not all that reformers were concerned about. Improving the tenements was also necessary to maintain social order, they believed. Middle class reformers feared not just general crime, but potential class warfare. Working class resentment broke out into rioting on several occasions in the 19th century. o In 1863, the year in which Lucas Glockner built 97 Orchard Street, the Draft Riots erupted. o Armed mobs revolted against the enforcement of the first federal draft, setting fires, destroying property, attacking African Americans and Republican Party members and even killing some black New Yorkers. o One eyewitness drew a connection between the riots and the conditions in which the rioters lived: “The high brick blocks and closely packed houses where the mobs originated, seemed to be literally hives of sickness and vice. It was wonderful to see, and difficult to believe, that so much misery, disease and wretchedness can be huddled together and hidden by high walls, unvisited and unthought of, so near our own abodes...the elements of popular discord are gathered in these wretchedly constructed tenement houses.” 6 “Middle Class Values” By the turn of the century, with epidemics and massive fire less of a threat, reformers also turned their attention to more subtle goals. They railed against the crowdedness of tenements not just as a source of disease, but as a corrupting influence on the poor. The use of parlors as bedrooms and young women washing up at hallways sinks led to promiscuity, they feared. The unbearable conditions of tenement apartments led to too much time spent socializing in the street. The jumble of activities inside the small apartments violated the “natural” domestic order, as it was perceived in the Victorian era. Common water closets and sinks were even seen as communist. Reformers sought to encourage among immigrants a more private home life, an investment in middle class values and aesthetics. But for that to happen, tenements had to provide their tenants with the basics of a proper home, and, in general, be more livable. Reformers’ Motivations This group believed they were on a moral crusade. As business and property owners, however, their motives were more complex. o Epidemics and worker unrest took their toll on the economy. Fire could result in property loss. o They had a stake in preventing these things, as well as encouraging immigrants to adopt a “proper” home life. o For these reformers, placing the blame for disease on specific germs rather than the housing conditions themselves posed a weaker challenge to the landlord/tenant relationship and to capitalism itself. Yet this group also recognized that improving housing conditions was a public good and a necessity. The 1901 Tenement House Act The Tenement House Act of 1901 was a pivotal turning point. The act had great impact both on future tenement construction and on existing tenements, as, for the first time, it was retroactive. “New Law” tenements – those built after 1901 – were designed quite differently than “Old Law” tenements, since they were required to have courtyards, making it impractical to build on one 25x100 square foot lot. It required the installation of indoor plumbing in all tenements (mostly indoor plumbing, although the law allowed for weatherproofed outdoor toilets), as well as increased ventilation and light. o For 97 Orchard Street, this meant installing hallway water closets and an airshaft. o Similar construction took place up and down the block – 95 and 99 Orchard Street got their hallway toilets around the same time, and, citywide, thousands of school sinks and privies were torn out and toilets installed between 1904 and 1907. 7 The 1901 Tenement House Act brought buildings like 97 Orchard Street a significant step closer to modern day standards for multiple family dwellings. In addition, the act created, for the first time, a separate bureaucratic entity to enforce the new law: the Tenement House Department and its squad of tenement inspectors. o The enforcement of earlier tenement laws had fallen to the Board of Health and the Buildings Department. o But with the creation of the Tenement House Department, responsibilities that had gone to separate parts of the municipal government were consolidated, and housing regulation was prioritized by separating it from the regulation of other buildings. o The Tenement House Department still encountered great difficulty, but it was a step forward. See the Tenement Encyclopedia: Andrew Dolkart, for more on housing law and the reform movement. Enforcement: The Tenement House Department One of the most significant aspects of the 1901 Tenement House Act was that it created the Tenement House Department to enforce it. The department was made up of: o A new Buildings Bureau, which oversaw tenement construction o A Bureau of Inspection o A clerical department, the Bureau of Records. It was the Bureau of Inspection, or Old Buildings Bureau, whose staff of inspectors who went into existing tenements, checked to see if they complied with the law, and noted violations. The Court Case That Decided the Tenement House Act Tenement House Department of City of New York v. Moeschen After 1901, most tenement owners in NYC did not undertake the changes required for toilet facilities. In 1903 the Tenement House Department brought legal action against Katie Moeschen, owner of a tenement at 332 East 39th Street, for failure to comply with the requirements of the 1901 act. The United Real Estate Owners' Association made this a test case to determine the legality of this provision of the law. An agreement was reached between the Owners' Association and the City’s Corporation Council, stipulating that the case would be framed in such a way that a final decision would apply to all buildings in the city with inadequate toilets. At the Municipal Court trial, the defendant's lawyer argued that the Tenement House Act violated of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution because it deprived an individual of property; that it imposed an unreasonable, arbitrary, and unfair requirement on owners without due process of law or adequate compensation and was, therefore, illegal. 8 He asserted that the school sinks were legal because they had been installed prior to 1890 in response to an order from the Board of Health. The jury ruled in favor of the city and the case was appealed all the way to the Supreme Court (1905) where the provision was upheld. Tenement Inspectors The Tenement Inspectors, 1902 Qualifications For this new occupation, the Department sought men and women with certain strengths. The educational requirements were modest. o A college education was not necessary but beneficial, since an inspector must be able to write a report, do the arithmetic and understand building construction and plumbing. Much more important were character, interpersonal skills and a sense of moral and social responsibility. o A 1910 textbook for potential inspectors stated: 9 “A tenement house inspector should be sober, vigilant, honest, consciences, and constantly bear in mind that upon the proper performance of his duties depend the welfare, comfort, health and the very life of the community in his charge...All employees must conduct themselves in a quiet, civil and gentlemanly manner, and be polite and considerate in their intercourse with the public and with each other. Abuse, insolence or loud talking will not be tolerated. Kindly but firm and tactful treatment of the public is essential...” Tenement Inspectors Badge, c. 1903 Who Were They? Who were these civil servants, charged with safeguarding the welfare of tenement dwellers and of society in general? They were usually not drawn from the tenements themselves, genealogical research suggests. Many were uptowners of middle class or even upper middle class origins, children of immigrants who eventually left the Tenement House Department for more prestigious careers. o For example, Charles Bretzfelder, who inspected 97 Orchard Street in 1902 at the age of 21, lived with his family in Yorkville, in a multiple-family dwelling quite unlike 97 Orchard Street: all but one of the five families in the building had a live-in servant. o By 1904 Bretzfelder had left tenement inspection to open his own law office. Yet some inspectors did have more in common with the tenants of the dwellings they visited. o Patrick Crimmins, a 40-year old father of four, inspected 95 Orchard Street in 1912. o In his own building, also located uptown, he counted among his ethnically diverse neighbors garment workers—a cloak finisher, a machine operator, a garment factory 10 “forelady”—as well as a stone mason, a dressmaker, a bankteller, two bookkeepers and the proprietor of a grocery store. What the Job Entailed Clad in the required uniform and armed with a badge, a fountain pen, and, according to one newspaper report, a torch, matches and a burglar's jimmy, an inspector entered a building and evaluated its condition, top to bottom as well as its outside, noting violations, and, hopefully, taking good notes. If the department had received a complaint letter, the inspectors were not informed who had made the complaint. This was so they could “truthfully assure the irate landlord who demands the name of the complaint-maker” that they did not know it.2 Building owners were notified of their violations and ordered to make changes. o If they did not, they were fined, and might eventually be prosecuted. o In a small number of cases, buildings were vacated because they were uninhabitable. I-Cards Inspectors were expected to record the building’s condition on an “I” card and sketch a diagram, to scale. o According to Andrew Dolkart, the “I” stood for “improvements.” o However, General instructions of the Tenement House Department, issued in 1906, states the “I” is short for “initial,” as in initial inspection, since the I-card had “for its aim only the determination of certain matters of structural condition in the premises.” A Department guidebook from 1906 states: “The accuracy of the records of the Department, a matter of utmost value and importance, depends entirely upon the care and skill with which the various report cards are filled out. It is therefore essential that all inspectors should exercise great care, fill out the cards distinctly, and in such a manner that when the report is complete it will be just as clearly intelligible to the to the office force as it is to the man on the ground. Any information necessary to produce in the mind of the office clerk a mental picture of the structure, and its surroundings, must appear on the card. If it is requisite to refer to the Inspector for further information, this is proof positive that the report is incomplete and imperfect.” 2 Sayles, p. 117 11 1902 I-Card, 97 Orchard Street Challenges Tenement inspectors faced many challenges. There were a huge number of tenements in the city, and many of these violated the law. Landlords who saw the law as an obstacle to their profit sometimes made enforcement harder, and tenants sometimes filed false complaints. Inspectors also encountered problems within the Tenement House Department itself. It was: o Constantly under assault by housing regulations’ opponents. o Tangled in battles between the mayor and Tammany Hall. o Underfunded and understaffed. o Inspectors' pay was low (in 1910, annual salary was $2,000) and their ranks compromised by corruption. o Turnover was high as inspectors left for better-paying work or were dismissed for impropriety. The Consequences These problems affected the success of the Department. An account by an inspector who worked in 1900 describes tenement inspection as an inconsistent practice, with inspectors ignoring poor and unhealthy condition at times. o Several times the inspector was offered bribes. The Rewards Yet the job, while difficult, could also be rewarding, a chance to affect change. 12 In 1903, a New York Daily Tribune reporter followed a female inspector on her rounds, describing her as vigorous and thorough. o She “mounts miles of stairs in a day without losing the least spring from her step.” o This inspector was a physician but joined the Department, feeling it was “quite as legitimate and much more reasonable to prevent disease than to treat it afterward.” Was it Successful? How successful was the Tenement House Department? Within ten years of the passage of the 1901 Act, virtually all tenements were at least partially in compliance with the law. School sinks were a thing of the past. o Thousands had been removed between 1905 and 1907, and by 1914 there were no occupied tenements still reliant on school sinks except a few that lacked access to sewer lines. Tenements also became better lighted. o “The dark room evil is steadily approaching extinction,” wrote the Tenement House Department Commissioner in 1914. o Still, there were still over 80,000 “dark rooms” in 1912. Most of the violations inspectors were finding involved garbage, filth and disrepair. o For example, the Department received an average of 36,000 complaints about tenements per year in 1911 to 1912, and almost half charged a lack of cleanliness. o A great deal of the work the Department accomplished involved removing garbage, cleaning, providing garbage receptacles, whitewashing, painting and miscellaneous repairs. By this time, government regulation of housing conditions had come to be thought of as necessary by the public, and even by landlords and builders. The initial result of the passage of the 1901 Act had been a construction slowdown. o Believing New Law Tenements weren't worth the cost to construct them, almost no one built a new tenement in 1901 only a small number were built the next year. Developers soon discovered that it cost only slightly more to build a New Law tenement than it did to bring Old Law building up to code, and that these new buildings had lower vacancy rates as they drew tenants from Old Law structures. o Construction rates rose again, and by 1913 nearly one billion dollars had been spent on the construction of over 22,000 New Law Tenements which housed nearly 1.5 million people. The Department was able to accomplish much in its lifetime, despite obstacles. It was phased out of existence by the creation of the Department of Housing and Buildings in 1938. An evaluation of its performance by the Charity Organization Society was rather critical of the Department. o It cited a lack of funding and an overwhelming caseload. A complete survey of all tenements was only accomplished twice, in 1909 and in the late 1930s. o The report also accused the department of narrowly focusing on apprehending violators of housing law rather than on achieving improved conditions. 13 o The report also criticized the inspectors themselves: “The personnel...had been selected many years ago on standards so low that it could hardly be expected that the inspectors would be able to do a job that had great social value. The methods were in the main those that had been laid down more than thirty years previously when the department was organized.” o Yet the same evaluation noted that many of the conditions that had existed before the Department’s existence had been eradicated. o Buildings like 97 Orchard Street illustrate this; changes were made when the law called for them, or the building was closed. That so many people find 97 Orchard Street’s conditions shocking today is a testament to how greatly standards have changed. 14 Appendix C: Tenement House Department Report: July-Sept, 1906 15 16 17 18