Why is schizophrenia so common?

advertisement

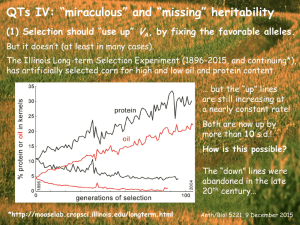

Why is schizophrenia so common? It afflicts more than 1 in 200 people. It is highly heritable. And it dramatically lowers fitness. “There is little doubt about the existence of a fecundity deficit in schizophrenia. Affected individuals have fewer children than the population as a whole. This reduction is of the order of 70% in males and 30% in females. The central genetic paradox of schizophrenia is why, if the disease is associated with a biological disadvantage, is this variation not selected out? To balance such a significant disadvantage, a substantial and universal advantage must exist. Thus far, all theories of a putative advantage have been disproved or remain unsubstantiated.” – From the Wikipedia article “Schizophrenia” “Data from a PET [positron emission tomography] study suggest that the less the frontal lobes are activated (red) during a working memory task, the greater the increase in abnormal dopamine activity in the striatum (green), thought to be related to the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia.” Anth/Biol 5221, 7 December 2009 And the heritabilities are amazing! (Thank you, twins!) Note that several conditions considered distinct “diseases” by mental-health professionals are strongly correlated genetically (MZ twins are diagnosed with different ones of them much more often than are DZ twins). This has fueled debate about the reality of the distinctions. 1 What is the genetic basis of these susceptibilities? Mutations in a few genes with large effects? If so, which genes are they? Or is it polymorphisms at many loci, each making a small contribution? And in either case, what kinds of mutations are involved? Unconditionally deleterious? Or good-news/bad-news tradeoffs? Amino-acid and nucleotide substitutions? Or duplications and deletions (copy-number variation)? QTL mapping studies suggest that there are genes with major effects on many chromosomes 2 There are a number of plausible “candidate” genes Many of these play well established roles in neurotransmission, in or near synapses. 3 But there’s a big problem: The major-effect genes explain just a fraction of the heritability! Where’s the rest of it? Could susceptibility be a highly polygenic quantitative trait? This was proposed more than 25 years ago by Irving Gottesman. But if that’s the case, where is all this heritable variation hiding? And why is there so much of it, given that selection against schizophrenia is very strong? American Journal of Human Genetics 35, 1161-1178 (1983) One possibility: frequent copynumber mutations 4 But there are other possibilities, for example: (1) very many genes with alleles of very small effect (2) very many genes with alleles of infrequent effect (low penetrance) (3) complex genetic interactions (epistasis, dominance, etc.) (4) epigenetics (imprinting or other environmental “pseudo-heritability”) However, not all of these are good at explaining the very high levels of heritability seen in the twin studies and other direct pedigree analyses. Could our great susceptibility to schizophrenia and related disorders be, in part, a transitory side effect of recent rapid mental evolution? If so, is Wikipedia’s assertion necessarily correct? “The central genetic paradox of schizophrenia is why, if the disease is associated with a biological disadvantage, is this variation not selected out? To balance such a significant disadvantage, a substantial and universal advantage must exist.” 5