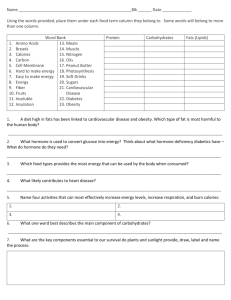

What Is Obesity?: Complementary Discourses By Cassandra

advertisement