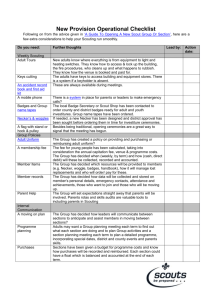

How the District Carries Out the Operational Mission of the Council

advertisement