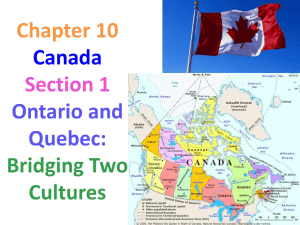

The Quebec referendums

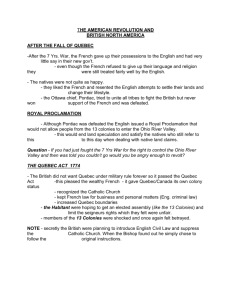

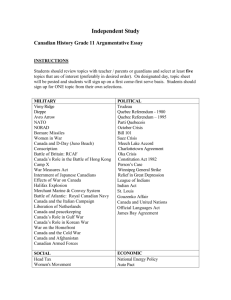

advertisement