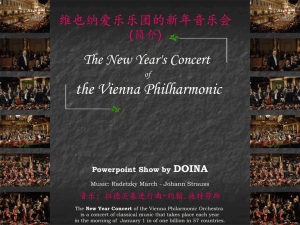

Views of an audience: Understanding the orchestral concert

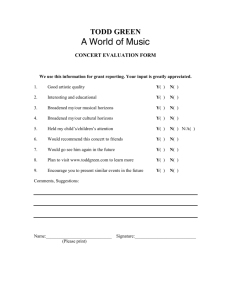

advertisement