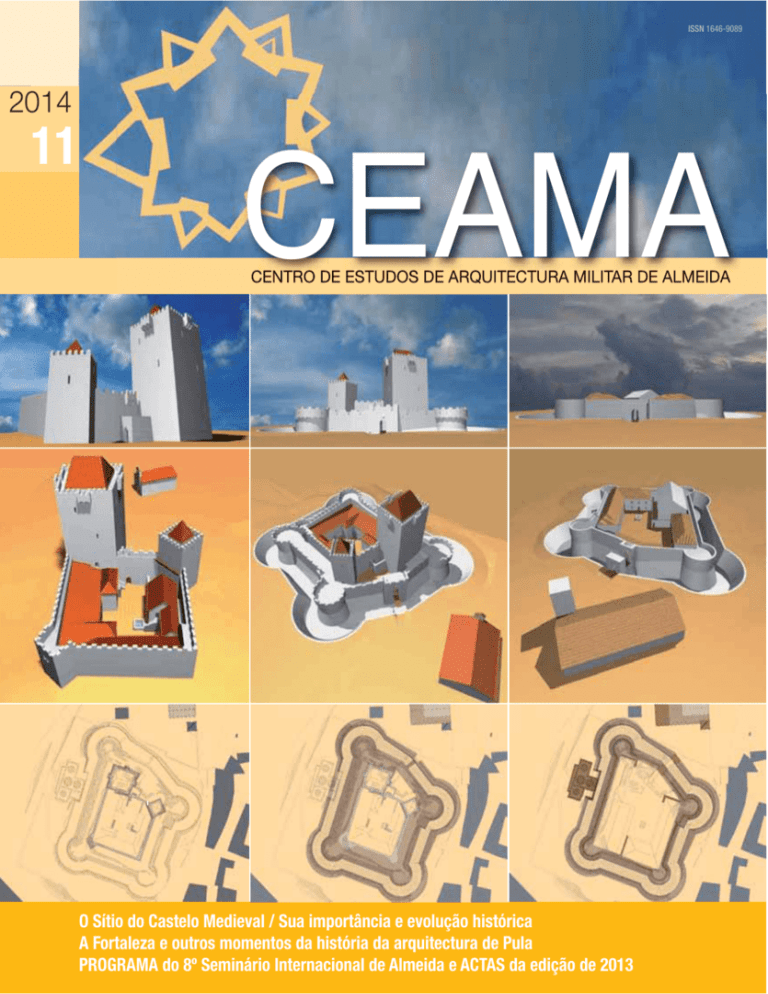

O Sítio do Castelo Medieval / Sua importância e evolução histórica

advertisement