1 Gender Diversity in Corporate Governance and Top Management

advertisement

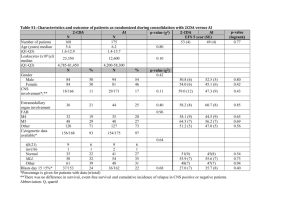

Gender Diversity in Corporate Governance and Top Management and Financial Performance Claude Francoeur HEC Montréal Réal Labelle Chair in Governance and Forensic Accounting HEC Montréal Bernard Sinclair-Desgagné Chair in International Economics and Governance HEC Montréal May 2006 * Financial support from the Autorité des marchés financiers and Desjardins Securities is gratefully acknowledged. 1 Gender Diversity in Corporate Governance and Top Management and Financial Performance Abstract By requiring that a majority of board members and all audit committee members be independent, the current reform introduces a greater degree of diversity of opinions and interests into corporate governance and keeps management’s control over the decision process within proper bounds. This article examines the concept of diversity by focusing on whether and how the participation of women in the firm’s governance and their presence among its senior management might enhance corporate performance. We build on the agency and stakeholder theoretical frameworks (Tirole 2001; Donaldson and Preston, 1995) to develop our main hypothesis relating gender diversity in the board room and among senior managers to corporate performance. We use the Fama and French (1992, 1993) valuation framework to take the level of risk into consideration when comparing firm performances, whereas previous studies used either raw stock returns or accounting ratios. Results indicate that firms operating in complex environments do indeed generate positive and significant abnormal returns, when they have a high proportion of women officers. Although the participation of women as directors does not seem to make a difference in this regard, firms with a high proportion of women in both their management and governance systems generate enough value to keep up with normal stock-market returns. Taken together, these results are compatible with the current efforts observed in some countries and organisations towards the adoption of normative policies for the advancement of women in business. Key words: Corporate governance; gender diversity; stakeholders. 2 1. Introduction Capital market participants, in particular institutional investors and ethical funds, are paying closer attention to the governance of listed companies in pursuing both the financial and social goals of their stakeholders. To that effect, the trend is towards greater diversity in governance. For instance, by requiring that a majority of board members and all audit committee members be independent, the current reform has already introduced a greater diversity of opinions and interests into corporate governance in order to keep management’s control over the decision process within proper bounds. The objective of this article is to examine the concept of diversity or pluralism in corporate governance by focusing on whether and how the participation of women in the firm’s governance and in senior management might enhance corporate performance. We study this facet of pluralism in governance by trying to provide answers to the following two research questions: - What are the characteristics or factors which lead firms to diversify their board of directors and their management team by appointing a greater percentage of women? - What is the impact of this diversity on the firm’s financial performance? Our measures of women’s participation in the firm’s governance and its top-level management are taken from the Catalyst’s1 2001-2004 annual surveys. Compared to previous studies, our contribution is twofold. We propose a theoretical framework relating corporate gender diversity to firm performance. We then conduct an empirical study to test the combined effect of diversity in governance and senior management on 3 the firm’s performance. Furthermore, whereas previous studies used either raw stock returns or accounting ratios, we apply the Fama-and-French (1992, 1993) valuation framework to take risk level into consideration when comparing firm performance. To develop our main hypothesis relating gender diversity on the board and in top management to corporate performance, we build on agency and stakeholder theoretical frameworks (Tirole 2001; Donaldson and Preston, 1995). In line with our hypothesis, results indicate that firms operating in complex environments which have a high proportion of women officers will generate positive and significant abnormal returns of approximately 6 % over three years. However, no significant excess returns are generated where women participate as directors or where their impact is measured by a score combining their representation as both officers and directors. Though it seems that the presence of women directors makes no difference as far as financial performance is concerned, firms with a high proportion of women in both their management and governance systems do generate enough value to keep up with normal stock-market returns. Taken together, these results are compatible with the current efforts some countries and organisations are making to adopt normative policies for the advancement of women in business. The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 proposes a theoretical framework for relating pluralism and, especially, gender diversity in corporate governance and high-level management to firm performance. Section 3 examines prior 1. Catalyst is the leading research and advisory organisation in North America working to advance women in business. 4 empirical evidence relevant to our study. Section 4 presents the data and the methodology used. The results of the empirical analysis are presented in section 5, while section 6 concludes the paper. 2. Theoretical development and hypotheses Over the years, the issue of gender diversity in the workforce has received a lot of attention both in the academic literature and in the popular press, particularly in studies addressing the “glass ceiling effect” (Farrell and Hersch 2001). This metaphor suggests a transparent barrier which women face as they attempt to achieve promotion into the higher levels of organizations (Li and Wearing 2004). Moreover, the presence of women on corporate boards is considered as the “ultimate glass ceiling” by some authors (Arfken et al., 2004). Our study relates to research that focuses on gender diversity or female representation in board and top-management positions (Adams and Ferreira, 2004; Kesner 1988; Bilimoria and Piderit 1994; Daily et al. 1999; Farrell and Hersch 2001) and on whether it can enhance corporate performance (Catalyst 2004; Carter et al., 2003; Adler 2001). Despite the topic’s latent interest , there are relatively few empirical academic studies linking gender diversity in corporate governance or in top management to firm performance. Yet , several studies have examined how other board characteristics may be 5 related to performance.2 Most of these begin with the assumption that the director’s effectiveness is a function of the board's independence from management. According to Fields and Keys (2003: 13), the issue of diversity may be linked to this more general issue of independent outside directors, since women and minorities are found to be more likely outsiders (Carter et al. 2003). From their review of these studies on boards of directors, Hermalin and Weisbach (2003) report that a number of regularities have emerged: notably, that board composition, a proxy for independence, does not seem to predict corporate performance, whereas board size is negatively related to performance. The unobservable nature of board independence may make it difficult to link it to performance, but this is not the case for the gender issue. One reason for this lack of attention to the gender issue (and the difficulty in establishing its clear-cut link with performance) may be because little formal theory has been developed on boards of directors, let alone on their gender diversity. Agency theory does provide an explanation for the existence of boards of directors as a response to agency problems but nothing with regard to a clear-cut prediction governing the relationship between gender diversity and performance. The objective of this paper is to contribute to the development and exploration of a theoretical framework aimed at linking gender diversity and performance . We use the agency and stakeholder theoretical frameworks (Tirole 2001; Donaldson and Preston, 1995) to develop our main hypothesis relating gender diversity in the board room and top 2 See, for instance, Bhagat and Black, 2002; Hermalin and Weisbach, 1991; Kaplan and Reishus, 1990; 6 management to corporate performance. Agency theory In his Presidential address for the Econometric Society, Tirole (2001, p. 2) defines a “good” corporate governance structure as “one that selects the most able managers and makes them accountable to investors” (emphasis added). Up to now, however, the best means of implementing these desiderata are still being sought.3 As shown in the previous section, one possible means which has recently shown up on the agendas of academic researchers and corporate board members is increased gender diversity. Few women currently sit on the boards of major corporations. Yet, the preliminary empirical evidence, reviewed in section 3, suggests that better financial performance might result from increasing the female presence on corporate boards and among senior management. A common rationale for these findings would go as follows: women (like external stakeholders, ethnic minorities, and foreigners) often bring a fresh perspective on complex issues and this can help correct informational biases in formulating strategies and solving problems. While intuitively plausible and well-grounded in cognitive psychology and decision theory, this explanation largely overlooks the concrete tasks Klein, 1998. 3 Like most finance, accounting and economics scholars, we center here on how to foster shareholder value rather than on whether such an objective is legitimate. 7 mentioned in the above quote. Before it gives advice on strategy, for instance, a corporate board must first appoint the right person as CEO. Special attention will then be paid to the leadership style that seems most appropriate in the actual business landscape. An autocratic leader might do well in pulling the firm out of a financial crisis, but a more democratic leader will better stimulate creativity and intrapreneurship in highly competitive, innovation-driven industries [Rotemberg and Saloner 1993]. However, if preferences for leadership styles are more influenced by gender than by economic considerations, a diverse board might well end up making the wrong appointment, thereby providing an untimely leadership style (or no leadership at all). Corporate boards must also motivate and monitor the acting CEO. In appraising the latter’s work, female directors might put forward the interests of employees and other stakeholders on issues such as non-financial disclosures, career management, and job discrimination. But saddling the CEO with too many (often conflicting ) requirements might well blur the bottom line pursued and dilute incentives, as the more recent developments in agency theory currently show (see, for instance, Dixit 1996 and Heath and Norman 2004). From a theoretical standpoint, when one considers the overall impact of gender diversity on the various duties being assumed by a corporate board, it would seem impossible to predict that greater female participation will improve (or impair) corporate governance and, as an indirect consequence, corporate performance. Different factors seem to pull in different directions. To find out which of the factors identified are likely to prevail, we 8 must now turn to empirical research. This is what we shall endeavour to do in section 4. Stakeholder theory Before we turn to the empirical portion of this paper, let’s briefly examine what the stakeholder theory says on our research question. Though the agency theory framework has indeed been very often used to study phenomena concerning corporate governance and top management, firms have, in recent years, been increasingly pressured by shareholder activists, large institutional investors (Fields and Keys, 2003: 12), and politicians to appoint women as directors or officers. The assumption is that “greater diversity of the boards of directors should lead to less insular decision making processes and greater openness to change” (Westphal & Milton 2000). In other words, despite what we noted in the previous subsection as being the conceptual difficulty in establishing a clear link between diversity and performance, there do seem to be strong normative and business reasons for diversity. In this subsection, we consider stakeholder theory to explore them. Stakeholder theory has been advanced and justified in management literature on the basis of its descriptive accuracy, instrumental power, and normative validity (Donaldson and Preston, 1995: 65). Regarding the first perspective, many studies conducted— notably by the Conference Board (2005) and Catalyst (2001-2004)—have confirmed the descriptive accuracy of stakeholder theory by longitudinally tracking the presence of women on corporate boards 9 or among top managers. To explore its research question, our study relies mainly on the instrumental facet of stakeholder theory. This facet establishes a framework for examining the assumed relationship or connection between the achievement of various corporate performance goals and gender diversity. The principal focus of interest here is the proposition that corporations practicing stakeholder management—in our case, giving greater voice to women—will, other things being equal, be relatively successful. Dallas (2002) surveys some psychological research that attempts to explore the effects of group member characteristics and heterogeneity, such as gender diversity, on group decision-making. To summarize this line of research: It seems that, in today’s complex and rapidly changing business environment, when it comes to engendering better quality decisions, the advantages related to the knowledge, perspective, creativity, and judgment brought forward by heterogeneous groups may be superior to those related to the smoother communication and coordination expected from homogeneous groups. This superiority is achieved by taking a wider range of alternatives and consequences into consideration. We also grounded the above instrumental perspective of stakeholder theory on its normative aspect. We interpret this normative perspective as being less stringent than the instrumental one, in the sense that diversity is a sensible objective even if it does not necessarily lead to improved performance. From that perspective, even if no relationship 10 (neither negative nor positive) were found between diversity and performance, diversity would still be a good policy to pursue. This perspective has some empirical support. For instance, Dallas (2002) observes that issues such as family life and flexible work arrangements are given greater prominence in companies that attract both female executives and female board members. Norway has adopted a law with regard to the promotion of women in business and, more recently, one of Canada’s provincial legislatures has adopted a resolution to gradually increase to 50 % the proportion of women sitting on the boards of public institutions (Audet 2006). Many reasons for having women on boards and among top managers simply make good business sense and support instrumental as well as normative perspectives, reasons such as drawing from a wider range of available intellectual capital, catering to women’s purchasing power, role modeling and signalling to employees—particularly current female managers and potential recruits. 3. Prior empirical evidence Empirical research on an assumed relationship between gender diversity in governance and top management and corporate financial performance is sparse. This is especially true if studies dealing with other aspects of diversity such as racial, ethnic, cultural, etc. are omitted. In this section, we review the few studies that are directly relevant to our research question. 11 Using a sample of 200 large US firms, Shrader et al. (1997) fail to find any significant relation between the percentage of women in the upper echelons of management and firm performance. As for the participation of women on boards, they find a negative impact on performance. The authors note that the low percentages of women among top managers or on boards —4.5% and 8% respectively— could impair the validity of their findings. Performance is measured using accounting data such as return on assets (ROA), return on sales (ROS), return on investments (ROI), and return on equity (ROE). Adler (2001) shows a strong correlation between women-friendly firms and high profitability. The sample is composed of 25 Fortune 500 firms showing a strong record of participation of women in the executive suite. Three accounting measurements of operational performance are used (ROS, ROA and ROE). Carter et al. (2003) find a positive relationship between board diversity (in terms of women and minorities) and firm value. Using a sample of 638 Fortune 1000 firms, the results of this study suggest that a higher percentage of women and minorities on the board of directors can increase firm value, as proxied by Tobin’s Q. The study also shows that the proportion of women on boards is a significant determinant of the fraction of minority directors on boards. This research does not provide a clear-cut conclusion on the effect of the greater participation of women alone on the firm’s value. 12 Adams and Ferreira (2004) document that boards of directors tend to be more homogeneous when firms operate in riskier environments. On the basis that social homogeneity breeds trust, an argument put forward by Kanter (1977), this study shows that diverse boards receive additional compensation to palliate the decrease in homogeneity. This, in turn, may reduce the firm’s performance and decrease its value. On the other hand, “firms with more diverse boards hold more board meetings” and “female directors have fewer attendance problems at board meetings.” These later findings militate for the greater effectiveness of diverse boards. The net effect of gender diversity remains unclear. In 2004, Catalyst, a well-known organization often cited for its research on the place of women in business, has conducted a study on the presumed connection between gender diversity and financial performance. Using a sample of 353 Fortune 500 companies from 1996 to 2000, the research shows that gender diversity has a positive impact on financial performance, as measured by ROE and raw stock returns. Their measure of diversity is based solely on the participation of women as corporate officers. They conclude that the firms belonging to the top quartiles in terms of diversity achieve a higher financial performance than their counterparts in the lower quartile. 13 3. Data and methodology In this section, we present the data and methodology used, while underlining the steps we took to try to improve on previous research. Our measures of women’s participation in the firm’s governance and top management are respectively collected from the 2001 and 2003 Catalyst censuses of women board directors and from the 2002 and 2004 Catalyst censuses of women officers in the Financial Post’s list of the 500 largest Canadian firms. For the purpose of our study, we have combined the annual Catalyst data by computing the average representation of women over the two-year period. If a firm with 1 woman officer in one year has none in the other, it is accounted for as having an average of 0.5 women officers. When a company’s statistic is only available for one year, we have used it. Given the stability of the statistics as outlined by Catalyst in its latest census (2005, p. 1), these methodological choices should not bias our results. In 2005, the story of women in corporate governance in Canada continued to be the same as in previous years: slow growth. Women held 12.0 percent of all board seats among the FP500 companies, up from 11.2 percent in 2003— only a 0.8 point increase in two years, and consistent with the trends we have witnessed in the United States and Canada since we started counting women board directors. We have also computed a total percentage of women directors and officers to test the combined effect of diversity in governance and top management on the firm’s performance. This proportion is the sum of the number of women directors and the number of women officers divided by the total number of positions. Furthermore, to access the degree of variation in female representation across firms and 14 to test its hypothesised positive relation with performance, we have split the sample in three. This grouping allows us to compare firms in the first third— showing a low proportion of women— to those in the last third— exhibiting a high proportion of women. Indeed, our subsequent univariate and multivariate analyses will use this grouping to test for significant differences between the high and low groups as far as their performance, risk, and complexity are concerned. As most of the data used in this study are not normally distributed or skewed to the right, we shall use non-parametric tests to compare group means. As previous studies have underlined the fact that diversity should help to deal with risky and complex situations, we have developed a number of measurements to account for these factors. Our proxies for risk and complexity are the firm’s beta, the market-to-book ratio and the standard deviation of the analyst’s error forecasts. The Market-to-Book ratios are taken from Stock Guide which publishes monthly accounting data and financial ratios taken from the latest financial reports of Canadian public firms. Standard deviations of analyst’s error forecasts are obtained from the Institutional Brokers‘ Estimate System (IBES). Monthly average betas were computed from data obtained from the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) data bank. The few studies (Catalyst 2004, Carter et al. 2003, Adler 2001 and Shrader et al. 1997) that have examined the effect of diversity on long term-financial performance have used a simplistic approach to measure returns. Indeed, in measuring returns, they took no account of risk, which is a fundamental factor in finance when attempting to compare the 15 financial performance of firms. Following theses studies, we first compute monthly average gross returns for the period from January 2002 to December 2004. Then, to control for risk, we use the three-factor Fama/ French (1992, 1993) valuation model. This model is deemed to explain the firm’s return by its beta, its size and its book-to-market ratio. If it does not entirely explain the firm’s financial performance, i. e. if the alpha coefficient of the linear model is significant (to be interpreted as an abnormal return) this indicates an omitted variable. Running it separately for the firms with a low and a high proportion of women, we will reject the null hypothesis of no relation between the representation of women and firm performance if the alpha is significant in the case of firms with the highest proportion of women. 4. Results and analysis In this section, we first present statistics on the extent of the difference existing between firms with a low as opposed to those with a high proportion of women as officers, directors or both. We then present and interpret our univariate analyses of the factors which are presumed to characterize firms that diversify their board of directors and their senior management team by appointing women. Finally, we use the three-factor Fama/French (1992, 1993) model to examine the presumed relationship of this gender diversity with the firm’s financial performance. Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on the average representation of women officers (panel A) and directors (panel B) as well as on the combined measure of the proportion 16 of women officers and directors (panel C) in FP500 firms. It shows that, on average, women represent 10.8 % of the officers in FP500 firms, while they only hold 7 % of the board seats. Our combined measure shows an average of 9.1 % participation. The JarqueBera tests reject the nul hypothesis of normality of the distributions of women representation(s) Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the variables measuring the firms risk and complexity. Our proxy for complexity stands at an average of 1.77 when measured as the firm’s Market-to-Book ratio and at 0.04 when measured as the forecast’s standard deviation. In general, the Jarque-Bera tests reject the nul hypothesis of normality of the distributions of our measures of risk and complexity. Table 3 provides the firm’s average monthly returns for the period 2002 to 2004. Firms are grouped according to women’s participation as directors, officers or both. The average monthly returns are 1.43 %, 1.21 %, and 1.25% respectively. The slight difference in the number of firms between the three subcategories is due to the data available from the Catalyst censuses and the availability of the returns from the TSX data bank. The Jarque-Bera tests reject the nul hypothesis of normality for the distributions of average monthly returns. Table 4 compares the average monthly returns of firms with a low proportion of women officers to those with a high proportion (panel A). Then, the two groups of firms are again compared after being separated on both sides of the median between low and high 17 beta to take risk and complexity into consideration as required in theory. The same comparison is done for low and high market-to-book (panel B) and forecast standard deviation (panel C). Using non-parametric tests, none of the difference is statistically significant. Tables 5 and 6 repeat those comparisons for firms with women as directors and for firms with women as both officers and directors respectively. Again, generally, at the conventional level of 5%, there is no significant difference between the two groups when risk and complexity are taken into consideration. In summary, our non-parametric univariate analysis does not exhibit any statistically significant difference between the firms with low and high gender diversity even when taking risk and complexity into consideration. Therefore, the instrumental perspective of the stakeholder theory does not seem to be supported. But the results seem to be supportive of the normative perspective, which makes gender diversity a good policy to pursue even if no significant negative relationship is found between diversity and performance. Given these weak results obtained for our main hypothesis, let’s now proceed with our multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis In this section, we use a multivariate approach to determine whether gender diversity is associated with the firm’s financial performance. Our analysis is based on the threefactor Fama/French multivariate model (1992, 1993). This model is widely used in the literature to estimate a firm’s expected return as a function of its beta, its size and its book-to-market ratio (BM). Running it separately for the firms with a low and a high proportion of women, the null hypothesis of no relation between the representation of 18 women and firm performance will be rejected if alpha, representing abnormal returns, is significant in the case of firms with the highest proportion of women. R p t − R f t = a p + b p (R m t − R f t ) + s p SMB t + h p HML t where R p t − R f t is the monthly excess return of the portfolio of our sample firms over the risk free rate. R m t − R f t is the excess return required by the market over the risk free rate, as used in the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). SMB (Small minus Big) is the excess return required for investing in small firms rather than in big firms and HML (High minus Low) is the excess return required for value firms (high book-to-market ratios) as opposed to growth firms. The portfolio and market returns are calculated on an equally weighted basis. The intercept “ a ” indicates the monthly average abnormal return of our sample. We use weighted least squares regressions to control for the heteroskedacity potentially induced by the fact that the number of firms in our monthly portfolios fluctuates over time. Our weights are the reciprocal of the square root of the number of firms in each month. In order to account for size and book-to-market peculiarities in Canada, b, s and h coefficients were estimated using all Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) returns for the period from 1990 to 2004. To compute SMB, following Fama and French (1992, 1993), we sorted all stocks into 6 portfolios and ranked them based on their size and BM ratios. The stocks were subsequently sorted into two size groups and three BM subgroups. Firms above median size were designated “big” and firms below median, “small.” Firms in the bottom 30% in terms of BM ratio were designated “low” and those in the top 30% were 19 designated “high.” The SMB factor represents the average excess return of small firms over big firms. The HML factor represents the average excess return of value firms (high BM ratios) over glamour or growth firms (low BM ratios). In order to validate our parameters, for every month from January 1990 to December 2004, we formed 25 portfolios using the size and book-to-market ratios of all TSX firms for which we found values in the Stock Guide database. For every month, we ranked and sorted all firms into five groups based on size and into five subgroups based on BM ratio. For every month, we ran 25 regressions of the Fama and French model. We used 91-day Canadian Government Treasury Bills as a proxy for the risk free rate (Rf). The market return is the equally weighted value of all stocks quoted on the TSX. As expected by the Fama and French model, our results show that the SMB and HML factors used are significant drivers of excess returns for Canadian firms.4 Table 7 shows that firms operating in complex environments, as measured by high betas, high market-to-book ratios or analysts’ forecasts standard deviation, generate positive and significant abnormal returns when they have a high proportion of women officers. From an economic perspective, the observed excess return is in the order of 6 % over three years (0.17 % compounded over 36 months). This result is robust whatever measurement of complexity used and supports the instrumental view of stakeholder theory. 4 These analyses are available upon request 20 Tables 8 and 9 show that women acting as directors or as measured by a score combining the representation of both officers and directors do not generate significant excess returns. Those results indicate that although the participation of women as director does not seem to make a difference as far as financial performance is concerned, firms with a high proportion of women are able to generate enough value to keep up with normal stock-market returns. 5. Conclusions Tirole (2001: 2) defines a “good” corporate governance structure as “one that selects the most able managers and makes them accountable to investors.”.However, to date. the best means of implementing these desiderata are still being sought. One possible means which has recently shown up on the agendas of academic researchers and corporate board members is increased gender diversity. Few women currently sit on the boards of major corporations. Yet, the preliminary empirical evidence, which we reviewed in section 3 of this article, suggests that better financial performance might result from increasing the female presence in these bodies. This article’s contribution to this line of research is twofold. We propose a theoretical framework for a relationship between gender diversity and firm performance. Then, we empirically test the combined effect of diversity in governance and top management on the firm’s performance. We use the Fama and French (1992, 1993) valuation framework to take the level of risk into consideration when comparing firm performances, while 21 previous studies either use raw stock returns or accounting ratios. We build on the agency and stakeholder theoretical frameworks to develop our main hypothesis of a relation between gender diversity in the board room and top management and corporate performance. Results indicate that firms operating in complex environments indeed generate positive and significant abnormal returns of approximately 6 % over three years, when they have a high proportion of women officers. This result is in line with our hypothesis. However, women participation as directors or as measured by a score combining their representation as both officers and directors does not generate significant excess returns. Although the participation of women as directors does not seem to make a difference as far as financial performance is concerned, firms with a high proportion of women in both their management and governance systems generate enough value to keep up with normal stock-market returns. Taken together, these results are compatible with the current efforts observed in some countries and organisations which seek the prescription of normative policies for the advancement of women in business. 22 Table 1 Representation of Women For the period 2001 to 2004 All firms A Officers 2002 and 2004 B Directors 2001-2003 C Directors and Officers 2001-2004 Number of firms Mean (%) Median (%) Maximum (%) Minimum (%) Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability Number of firms Mean (%) Median (%) Maximum (%) Minimum (%) Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability Number of firms Mean (%) Median (%) Maximum (%) Minimum (%) Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability 234 10.7808 9.1000 50.0000 0.0000 10.2617 1.0436 4.2693 58.1841 0.0000 229 7.0201 4.8000 50.0000 0.0000 8.1210 1.2489 5.5062 119.4605 0.0000 219 9.0639 8.1000 33.3000 0.0000 7.2113 0.6508 2.8818 15.5871 0.0004 Low Percentage High Percentage firms firms 78 0.4910 0.0000 4.8000 0.0000 1.3137 2.3867 6.9853 125.6693 0.0000 105 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 72 1.5361 0.0000 4.9000 0.0000 1.8179 0.4958 1.5474 9.2791 0.0097 74 22.8743 20.0000 50.0000 14.8000 7.8405 1.7065 5.9451 62.6620 0.0000 74 16.7392 15.4000 50.0000 10.5000 6.0358 2.6921 14.0616 466.6560 0.0000 73 17.4836 16.0000 33.3000 11.8000 4.6306 0.9922 3.7296 13.5974 0.0011 23 Table 2 Risk and complexity of the sample firms For the period 2002 to 2004 All Three year average monthly Beta Market-to-Book Forecast Std Deviation Number of firms Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability Number of firms Mean ratio Median Maximum Minimum Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability Number of firms Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability 179 0.6775 0.5505 2.9266 0.0036 0.5500 1.6758 6.2419 162.1679 0.0000 187 1.7714 1.5062 12.8900 0.0306 1.3556 3.7509 27.2250 5011.0340 0.0000 134 0.0401 0.0219 0.7978 0.0000 0.0791 7.0025 64.6301 22302.1100 0.0000 Low High Risk/Complexit Risk/Complexit y y 82 0.2714 0.2599 0.5217 0.0036 0.1468 0.0217 1.9748 3.5973 0.1655 95 0.9664 0.9997 1.5100 0.0306 0.3505 -0.3838 2.2749 4.4133 0.1101 70 0.0097 0.0091 0.0229 0.0000 0.0083 0.1500 1.4767 7.0303 0.0297 97 1.0207 0.8606 2.9266 0.5258 0.5318 1.7562 5.5160 75.4464 0.0000 92 2.6027 2.1587 12.8900 1.5421 1.5013 4.0747 25.9614 2275.6200 0.0000 64 0.0733 0.0420 0.7978 0.0230 0.1049 5.4241 37.0749 3410.0880 0.0000 24 Table 3 Average monthly returns Full sample of firms with women For the period 2002 to 2004 Officers Directors N Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability N Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability Directors & Officers N Mean Median Maximum Minimum Std Deviation Skewness Kurtosis Jarque-Bera Probability 233 0.0143 0.0137 0.1321 -0.1610 0.0316 -1.1504 10.7697 637.4724 0.0000 230 0.0121 0.0126 0.1321 -0.2044 0.0354 -1.9278 13.5376 1206.6110 0.0000 222 0.0125 0.0131 0.1321 -0.2044 0.0348 -1.9345 14.3560 1331.3240 0.0000 25 Table 4 Average Monthly Returns – Women Officers For the period 2002 to 2004 A Women Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) van der Waerden B N 78 74 Median 0.0127 0.0148 Value 0.4055 0.4055 0.1053 0.0263 0.1659 0.1659 0.1098 P-Value 0.6851 0.6851 0.7455 0.8711 0.6838 0.6838 0.7404 Women Officers Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) van der Waerden C All All N 75 69 Median 0.0126 0.0149 Value 0.6618 0.6618 0.2504 0.1113 0.4407 0.4407 0.3107 P-Value 0.5081 0.5081 0.6168 0.7387 0.5068 0.5068 0.5773 Women Officers Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) van der Waerden All N 51 54 Median 0.0119 0.0153 Value 0.7149 0.7149 0.0101 0.0090 0.5156 0.5156 0.5222 P-Value 0.4747 0.4747 0.9200 0.9244 0.4727 0.4727 0.4699 Low Beta N Median 39 0.0114 37 0.0135 Value 0.1611 0.1611 0.0527 0.0000 0.0276 0.0276 0.1039 P-Value 0.8720 0.8720 0.8185 1.0000 0.8679 0.8679 0.7472 Low Market-to-Book N Median 41 0.0125 35 0.0155 Value 0.3231 0.3231 0.4767 0.2118 0.1078 0.1078 0.0186 P-Value 0.7467 0.7467 0.4899 0.6453 0.7427 0.7427 0.8915 Low Forecast SD N Median 24 0.0128 31 0.0149 Value 0.4158 0.4158 0.0141 0.0235 0.1800 0.1800 0.2885 P-Value 0.6776 0.6776 0.9055 0.8782 0.6714 0.6714 0.5912 High Beta N Median 39 0.0190 37 0.0205 Value 0.6339 0.6339 0.0527 0.0000 0.4085 0.4085 0.4386 P-Value 0.5261 0.5261 0.8185 1.0000 0.5227 0.5227 0.5078 High Market-to-Book N Median 34 0.0142 34 0.0148 Value 0.3434 0.3434 0.0000 0.0588 0.1222 0.1222 0.3498 P-Value 0.7313 0.7313 1.0000 0.8084 0.7267 0.7267 0.5543 High Forecast SD N Median 27 0.0119 23 0.0157 Value 0.5061 0.5061 0.0805 0.0000 0.2661 0.2661 0.1670 P-Value 0.6128 0.6128 0.7766 1.0000 0.6060 0.6060 0.6828 26 Table 5 Average Monthly Returns – Women Directors For the period 2002 to 2004 A Women Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) van der Waerden B N 102 74 Median 0.0165 0.0110 Value 1.6064 1.6064 0.8394 0.5829 2.5853 2.5853 2.4312 P-Value 0.1082 0.1082 0.3596 0.4452 0.1079 0.1079 0.1189 Women Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) van der Waerden C All All N 102 70 Median 0.0165 0.0110 Value 1.7283 1.7283 0.8672 0.6022 2.9924 2.9924 2.7885 P-Value 0.0839 0.0839 0.3517 0.4377 0.0837 0.0837 0.0949 Women Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) van der Waerden All N 66 50 Median 0.0165 0.0114 Value 0.8223 0.8223 0.5624 0.3164 0.6808 0.6808 0.4127 P-Value 0.4109 0.4109 0.4533 0.5738 0.4093 0.4093 0.5206 Low Beta N Median 39 0.0156 43 0.0111 Value 1.3231 1.3231 0.0489 0.0000 1.7630 1.7630 1.7984 P-Value 0.1858 0.1858 0.8250 1.0000 0.1843 0.1843 0.1799 Low Market-to-Book N Median 61 0.0203 28 0.0128 Value 0.9675 0.9675 0.7078 0.3758 0.9446 0.9446 0.8989 P-Value 0.3333 0.3333 0.4002 0.5399 0.3311 0.3311 0.3431 Low Forecast SD N Median 38 0.0100 21 0.0106 Value 0.1187 0.1187 0.1360 0.0094 0.0160 0.0160 0.0800 P-Value 0.9055 0.9055 0.7123 0.9229 0.8992 0.8992 0.7773 High Beta N Median 63 0.0170 31 0.0109 Value 1.0857 1.0857 1.2033 0.7701 1.1875 1.1875 0.9355 P-Value 0.2776 0.2776 0.2727 0.3802 0.2758 0.2758 0.3334 High Market-to-Book N Median 41 0.0114 42 0.0107 Value 0.9427 0.9427 0.1076 0.0118 0.8973 0.8973 0.8075 P-Value 0.3458 0.3458 0.7429 0.9136 0.3435 0.3435 0.3689 High Forecast SD N Median 28 0.0189 29 0.0117 Value 1.8117 1.8117 2.9587 2.1173 3.3114 3.3114 2.9278 P-Value 0.0700 0.0700 0.0854 0.1456 0.0688 0.0688 0.0871 27 Table 6 Average Monthly Returns – Women Officers & Directors For the period 2002 to 2004 A Women Officers & Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) Van der Waerden B All N 72 73 Median 0.0165 0.0137 Value 1.0282 1.0282 0.5578 0.3373 1.0612 1.0612 1.1568 P-Value 0.3039 0.3039 0.4551 0.5614 0.3029 0.3029 0.2821 Women Officers & Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) Van der Waerden C All N 74 68 Median 0.0165 0.0139 Value 0.9985 0.9985 0.4515 0.2540 1.0010 1.0010 1.1179 P-Value 0.3181 0.3181 0.5016 0.6143 0.3171 0.3171 0.2904 Women Officers & Directors Low Percentage of Women High Percentage of Women Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney (tie-adj.) Med. Chi-square Adj. Med. Chi-square Kruskal-Wallis Kruskal-Wallis (tie-adj.) Van der Waerden All N 48 52 Median 0.0179 0.0136 Value 0.6589 0.6589 0.6410 0.3606 0.4387 0.4387 0.2895 P-Value 0.5100 0.5100 0.4233 0.5482 0.5078 0.5078 0.5906 Low Beta N Median 28 0.0126 37 0.0146 Value 0.5100 0.5100 0.1545 0.0203 0.2669 0.2669 0.4536 P-Value 0.6100 0.6100 0.6942 0.8866 0.6054 0.6054 0.5006 Low Market-to-Book N Median 45 0.0217 29 0.0155 Value 1.2180 1.2180 0.5103 0.2268 1.4970 1.4970 1.7284 P-Value 0.2232 0.2232 0.4750 0.6339 0.2211 0.2211 0.1886 Low Forecast SD N Median 23 0.0170 27 0.0114 Value 0.1363 0.1363 0.0805 0.0000 0.0213 0.0213 0.0003 P-Value 0.8916 0.8916 0.7766 1.0000 0.8839 0.8839 0.9858 High Beta N Median 44 0.0181 36 0.0115 Value 0.6480 0.6480 1.8182 1.2626 0.4261 0.4261 0.2739 P-Value 0.5170 0.5170 0.1775 0.2612 0.5139 0.5139 0.6007 High Market-to-Book N Median 29 0.0114 39 0.0135 Value 0.2232 0.2232 0.0601 0.0000 0.0526 0.0526 0.2385 P-Value 0.8234 0.8234 0.8063 1.0000 0.8186 0.8186 0.6253 High Forecast SD N Median 25 0.0189 25 0.0137 Value 0.9119 0.9119 0.7200 0.3200 0.8494 0.8494 0.7563 P-Value 0.3618 0.3618 0.3961 0.5716 0.3567 0.3567 0.3845 28 Table 7 Fama & French Three Factor Model – Women Officers For the period 2002 to 2004 Women Officers Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months Women Officers Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months Women Officers Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months All Low Beta High Beta 0.0001 0.1143 0.9098 0.6731 32 0.0001 0.1858 0.8539 0.6105 33 0.0001 0.0995 0.9215 0.5890 32 0.0006 1.2020 0.2388 0.7428 34 -0.0001 -0.0587 0.9535 0.3843 34 0.0017 1.8215 0.0785** 0.7853 34 All Low Market-to-Book High Market-to-Book 0.0000 0.0416 0.9671 0.6503 32 -0.0010 -0.9720 0.3391 0.5416 33 0.0007 1.1299 0.2678 0.7013 33 0.0006 1.2219 0.2312 0.7471 34 0.0000 -0.0037 0.9971 0.5455 34 0.0016 2.7891 0.0091*** 0.8092 34 All Low Standard Deviation of Forecast High Standard Deviation of Forecast 0.0003 0.4749 0.6384 0.6603 33 0.0005 0.6685 0.5093 0.5884 32 0.0004 0.2233 0.8248 0.5710 34 0.0008 1.6228 0.1151 0.7608 34 0.0011 1.3597 0.1844 0.4575 33 0.0019 1.8073 0.0807** 0.8028 34 ***, **, * Significantly different from zero at the 1, 5, and 10 percent levels, respectively. 29 Table 8 Fama & French Three Factor Model – Women Directors For the period 2002 to 2004 Women Directors Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months Women Directors Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months Women Directors Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months All Low Beta High Beta 0.0000 -0.0872 0.9311 0.7544 34 0.0001 0.1460 0.8849 0.5869 34 -0.0001 -0.1771 0.8606 0.7079 34 0.0000 -0.0557 0.9560 0.7372 34 0.0003 0.6114 0.5455 0.5367 34 -0.0006 -0.7079 0.4845 0.7252 34 All Low Market-to-Book High Market-to-Book 0.0001 0.1819 0.8569 0.7217 33 -0.0001 -0.1273 0.8995 0.6492 34 0.0000 0.0582 0.9540 0.7930 34 0.0000 -0.0557 0.9560 0.7372 34 0.0004 0.3353 0.7398 0.5343 33 0.0001 0.1680 0.8677 0.6367 34 All Low Standard Deviation of Forecast High Standard Deviation of Forecast -0.0001 -0.1465 0.8845 0.7684 34 -0.0006 -0.4814 0.6337 0.6588 34 0.0012 1.2834 0.2095 0.6345 33 0.0003 0.7198 0.4774 0.7065 33 -0.0005 -0.4596 0.6491 0.5777 34 0.0008 1.2275 0.2295 0.6214 33 30 Table 9 Fama & French Three Factor Model – Women Directors and Officers For the period 2002 to 2004 Women Directors & Officers Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months Women Directors & Officers Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months Women Directors & Officers Low Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months High Percentage of Women Alpha t-Statistic P-Value Adj. R Square Nb of Months All Low Beta High Beta 0.0003 0.4111 0.6841 0.6124 32 0.0003 0.3691 0.7148 0.5561 33 0.0000 0.0462 0.9634 0.6331 34 0.0004 1.1797 0.2477 0.7983 33 0.0002 0.2450 0.8081 0.4698 34 0.0006 0.7258 0.4736 0.8007 34 All Low Market-to-Book High Market-to-Book 0.0002 0.3902 0.6992 0.6872 33 0.0001 0.1053 0.9168 0.6552 34 -0.0003 -0.3184 0.7524 0.7127 34 0.0004 1.0712 0.2929 0.7643 33 0.0005 0.4596 0.6492 0.5717 33 0.0008 1.6034 0.1193 0.8103 34 All Low Standard Deviation of Forecast High Standard Deviation of Forecast 0.0000 -0.0507 0.9599 0.6704 33 -0.0007 -0.3471 0.7310 0.5029 33 0.0009 0.7899 0.4360 0.5668 33 0.0005 1.3827 0.1773 0.8150 33 0.0004 0.5039 0.6180 0.7310 34 0.0011 1.4495 0.1579 0.6654 33 31 References Adams, R. B. and D. Ferreira: 2004, “Gender Diversity in the Boardroom”, European Corporate Governance Institute, Finance Working paper # 57, 30 p. Adler, R.D.: 2001, “Women in the Executive Suite Correlate to High Profits”, Glass ceiling Research Center, http://glass-ceiling.com/InTheNewsFolder/HBRArticlePrintablePage.html. Arfken, D. E., Bellar, S. L. and M. M. Helms: 2004. “The Ultimate Glass Ceiling Revisited: The Presence of Women on Corporate Boards”. Journal of Business Ethics 50, 177–186. Audet, M.: 2006. “To modernize the Public Corporations Governance”. Statement of policy, 33 p. Bilimoria, D. and S. K. Piderit: 1994, “Board committee membership: Effects of sexbased bias”, Academy of Management Journal 37, 1453-1477. Bhagat, S. and B. Black: 2002, “The non-correlation between board independence and longterm firm performance”, Journal of Corporation Law 27, 2 (Winter), 231-273. Carter, D. A., B. J. Simkins and W. G. Simpson: 2003, The Financial Review 38, 33-53. Catalyst: 2004, “The Bottom Line: Connecting Corporate Performance and Gender Diversity”, Catalist Publication Code D58, New York, 28 p. Daily, C. M., C. S. Trevis and D. R. Dalton: 1999, “A decade of corporate women: Some progress in the boardroom, none in the executive suite”, Strategic Management Journal 20, 93-99. Dallas, L. L.: 2002, “The New Managerialism and Diversity on Corporate Boards of Directors”, Public Law and Legal Theory Working Paper 38 (Spring), University of San Diego School of Law (http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=313425), 30 p. 32 Dixit, A. K.: 1996, “The Making of Economic Policy: A Transaction-Cost Politics Perspective”, Cambridge (MA: MIT Press). Donaldson, T. and L. Preston: 1995, “The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications”, The Academy of Management Review 20 (1), 65. Fama, E.F. and K.R. French: 1992, “The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns”, The Journal of Finance 47 (2), 427-465. Fama, E.F. and K.R. French: 1993, “Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stocks and Bonds”, Journal of Financial Economics 33, 3-56. Farrell, K. A. and P. L. Hersch: 2001, “Additions to Corporate Boards: Does Gender Matter?”, Working paper, 30 p. Fields, M. A. and P. Y. Keys: 2003. “The Emergence of Corporate Governance from Wall St.: Outside Directors, Board Diversity, Earnings Management, and Managerial Incentives to Bear Risk”, The Financial Review 38, 1-24. Heath, J. and N. Wayne: 2004, “Stakeholder Theory, Corporate Governance and Public Management: What can the History of State-Run Enterprises Teach us in the Post-Enron era?”, Journal of Business Ethics 53, 247-265. Hermalin, B. and M. Weisbach: 2003. “Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution: A survey of the economic literature”, Economic Policy Review Federal Reserve Bank of New York 9 (1), 7-26. Hermalin, B.and M. Weisbach: 1991, “The Effects of Board Composition and Direct Incentives on Firm Performance”, Financial Management 20 (4), 101-12. Kanter, R. M.: 1977, “Men and Women of the Corporation”, New York, Basic Books. 348 p. 33 Kaplan, S. and D. Reishus: 1990, “Outside Directorships and Corporate Performance”, Journal of Financial Economics 27, 389-410. Kesner, I. F.:1988, “Directors’ characteristics and committee membership: An investigation of type, occupation, tenure and gender”, Academy of Management Journal 31, 66-84. Klein, A.: 1998, “Firm Performance and Board Committee Structure”, Journal of Law and Economics 41, 275-99. Li, C. A. and B. Wearing: 2004, “Between glass ceilings: Female non-executive directors in UK quoted companies”, International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 1 (4, Oct), 355-370. Conference Board: 2005. “Emerging Trends in Europe… Women in Leadership. The Diversity Imperative: Supporting Actions for Change”. By D. Palframan. Executive Action Series No. 158 (August), 7 p. Rotemberg, J. J. and G. Saloner: 1993, “Leadership Styles and Incentives,” Management Science 39 (11), 1299-1318. Shrader, C.B., V.B. Blackburn and P. Iles: 1997, “Women in Management and Firm Financial Performance: An Exploratory Study”. Journal of Managerial Issues 9 (3) (Fall), p. 355-372. Tirole, J.: 2001, “Corporate Governance,” Econometrica 69 (1), pp. 1-35. Westphal, J. D. and L. P. Milton: 2000, “How experience and network ties affect the influence of demographic minorities on Corporate Board”. Administrative Science Quarterly 45 (2), 366-417. 34