SPORTS AND IDENTITY Case study: Czech Republic and Ice Hockey

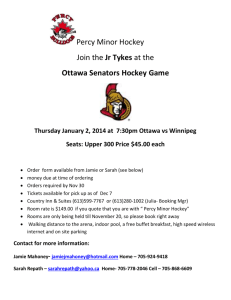

advertisement