Prokaryote -( Wikipedia,)

advertisement

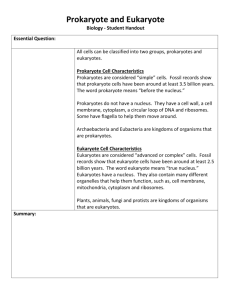

Prokaryote - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1 of 3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prokaryote Prokaryote From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Prokaryotes (pro-KAR-ee-oht) (from Old Greek pro- before + karyon nut or kernel, referring to the cell nucleus, + suffix -otos, pl. -otes; also spelled "procaryotes") are organisms without a cell nucleus (= karyon), or indeed any other membrane-bound organelles, in most cases unicellular (in rare cases, multicellular). Contents 1 Relationship to eukaryotes 2 Genes 3 Colonies 4 Structure 5 Environment 6 Evolution of prokaryotes 7 References 8 See also 9 External links Prokaryotic bacteria cell structure Relationship to eukaryotes Prokaryotes are very distinct from eukaryotes (meaning true kernel, also spelled "eucaryotes") because eukaryotes have true nuclei containing their DNA, while prokaryotes' genetic material is not membrane-bound. Eukaryotes are organisms that have cell nuclei and may be variously unicellular or multicellular. An example of an eukaryote would be a human. The difference between the structure of prokaryotes and eukaryotes is so great that it is considered to be the most important distinction among groups of organisms. Most prokaryotes are bacteria, and the two terms are often treated as synonyms. In 1977, Carl Woese proposed dividing prokaryotes into the Bacteria and Archaea (originally Eubacteria and Archaebacteria) because of the significant genetic differences between the two. This arrangement of Eukaryota (also called "Eukarya"), Bacteria, and Archaea is called the three-domain system replacing the traditional two-empire system. The cell structure of prokaryotes differs greatly from eukaryotes in many ways. The defining characteristic is the absence of a nucleus or nuclear envelope. Prokaryotes also were previously considered to lack cytoskeletons and do lack membrane-bound cell compartments such as vacuoles, endoplasmic reticulum/endoplasmic reticula, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and chloroplasts. In eukaryotes, the latter two perform various metabolic processes and are believed to have been derived from endosymbiotic bacteria. In prokaryotes similar processes occur across the cell membrane; endosymbionts are extremely rare. Prokaryotes also have cell walls, while some eukaryotes, particularly animals, do not. Both eukaryotes and prokaryotes have structures called ribosomes, which produce protein. Prokaryotes are usually much smaller than eukaryotic cells. Taking into account membrane bound organelles, prokaryotes also differ from eukaryotes in that they contain only a single loop of DNA stored in an area named the nucleoid. The DNA of the eukaryote is found on chromosomes. Prokaryotic DNA also lacks the proteins found in eukaryotic DNA. Prokaryotes have a larger surface area to volume ratio. This gives the Prokaryotes a higher metabolic rate, a higher growth rate and thus a smaller generation time as compared to the Eukaryotes. Genes Nearly all prokaryotes have a single circular chromosome contained within a conglomeration of ribosomes and other proteins related to transcription and translation region called the nucleoid, as opposed to the well defined, double membrane bound eukaryotic nucleus. Certain exceptions do apply, however. For example, Borrelia burgdorferi and the genus Streptomyces contain linear chromosomes, like the eukaryotes. Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, has two circular chromosomes, the smaller of which contains most of the genes responsible for virulence. Most notable, however, are the plasmids, which are small (about 1 to 10 thousand base pairs), circular pieces of DNA that are replicated by the host's DNA replication machinery, but whose genes are not absolutely critical for general survival. In nature, they usually contain special genes that confer some type of selective advantage such as antibiotic resistance, virulence, or gene transfer mechanisms. In 2/8/2007 11:32 AM Prokaryote - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2 of 3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prokaryote genetic engineering artificially introduced plasmids carry genes to be expressed and studied. Prokaryotes also differ from eukaryotes in the structure, packing, density, and arrangement of their genes on the chromosome. Prokaryotes have incredibly compact genomes compared to eukaryotes, mostly because prokaryote genes lack introns and large non-coding regions between each gene. Whereas nearly 95% of the human genome does not code for proteins or RNAs or includes a gene promoter, nearly all of the prokaryote genome codes or controls something. Prokaryote genes are also expressed in groups, known as operons, instead of individually, as in eukaryotes. In a prokaryote cell, all genes in an operon(three in the case of the famous lac operon) are transcribed on the same piece of RNA and then made into separate proteins, whereas if these genes were native to eukaryotes, they each would have their own promoter and be transcribed on their own strand of mRNA. This lesser degree of control over gene expression contributes to the simplicity of the prokaryotes as compared to the eukaryotes. It is worth noting that one of the most convincing pieces of evidence for the endosymbiotic theory of the origin of mitochondria is that mitochondrial genomes look like prokaryotic genomes, replete with circular genomes, operons, and plasmids, while that of the host follows the eukaryotic model. Reproduction is most often asexual, through binary fission, where the chromosome is duplicated and attaches to the cell membrane, and then the cell divides in two. However, they show a variety of parasexual processes where DNA is transferred between cells, such as transformation and transduction. Colonies While prokaryotes are nearly always unicellular, some are capable of forming groups of cells called colonies. Unlike many eukaryotic multicellular organisms, each member of the colony is undifferentiated and capable of free-living (but consider cyanobacteria, a very successful prokaryotic group which does exhibit definite cell differentiation). Individuals that make up such bacterial colonies most often still act independent of one another. Colonies are formed by organisms that remain attached following cell division, sometimes through the help of a secreted slimy layer. Structure Recent research indicates that all prokaryotes actually do have cytoskeletons albeit more primitive than those of eukaryotes. Besides homologues of actin and tubulin (MreB and FtsZ) the helically arranged building block of flagellum, flagellin is one of the most significant cytoskeletal protein of bacteria as it provides structural backgrounds of chemotaxis, the basic cell physiological response of bacteria. At least some prokaryotes also contain intracellular structures which can be seen as primitive organelles. Membranous organelles (a. k .a. intracellular membranes) are known in some groups of prokaryotes, such as vacuoles or membrane systems devoted to special metabolic properties, e. g. photosynthesis or chemolithotrophy. Additionally, some species also contain protein-enclosed microcompartments mostly associated with special physiological properties (e. .g. carboxysomes or gas vacuoles). The sizes of prokaryotes relative to other organisms and biomolecules. Environment Prokaryotes are found in nearly all environments on earth. Archaea in particular seem to thrive in harsh conditions, such as high temperatures or salinity. Organisms such as these are referred to as extremophiles. Many prokaryotes live in or on the bodies of other organisms, including humans. Evolution of prokaryotes It is generally accepted that the first living cells were some form of prokaryote and may have developed out of protobionts. Fossilized prokaryotes approximately 3.5 billion years old have been discovered, and prokaryotes are perhaps the most successful and abundant organism even today. In contrast the eukaryote only appeared between approximately 1.7 and 2.2 billion years ago [1]. While Earth is the only known place where prokaryotes exist, some have suggested structures within a Martian meteorite should be interpreted as fossil prokaryotes; this is open to considerable debate and skepticism. Prokaryotes diversified greatly throughout their long existence. The metabolism of prokaryotes is far more varied than that of eukaryotes, leading to many highly distinct types of prokaryotes. For example, in addition to using photosynthesis or organic compounds for energy like eukaryotes do, prokaryotes may obtain energy from inorganic chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide. 2/8/2007 11:32 AM Prokaryote - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 3 of 3 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prokaryote This has enabled the bacteria to thrive and reproduce. Today, archaebacteria can be found in the cold of Antarctica and in the hot Yellowstone springs. References 1. ^ Scientific American, October 21, 1999 (http://www.sciam.com/askexpert_question.cfm?articleID=000C32DD-60E1-1C72-9EB7809EC588F2D7&catID=3&topicID=3) See also Monera – previously Prokaryota were a Kingdom with divisions of eubacteria and archaebacteria. Bacterial cell structure Nanobe Virus Prion Protist Symbiogenesis External links This article contains material from the Science Primer (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/About/Primer) published by the NCBI, which, as a US government publication, is in the public domain. Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prokaryote" Category: Prokaryotes This page was last modified 23:49, 5 February 2007. All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License. (See Copyrights for details.) Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a US-registered 501(c)(3) tax-deductible nonprofit charity. 2/8/2007 11:32 AM