Legislative Findings, Congressional Powers, and the Future of the

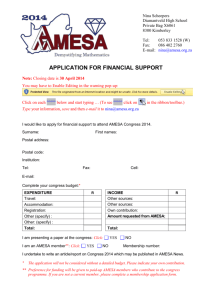

advertisement