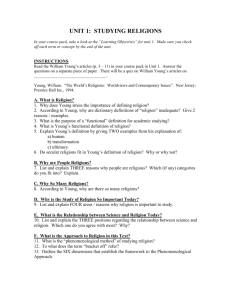

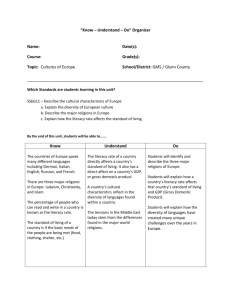

Learning about World Religions in Public Schools

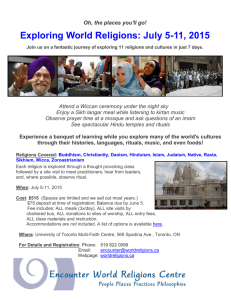

advertisement