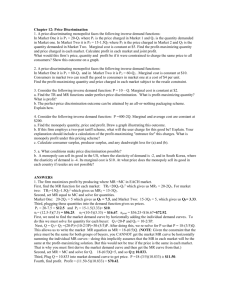

Chapter 12: Pricing

advertisement