The Nestlé Infant Formula Controversy and a Strange Web of

advertisement

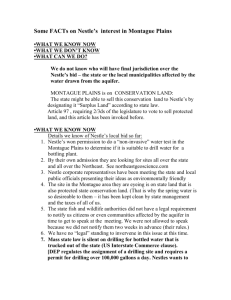

The Nestlé Infant Formula Controversy and a Strange Web of Subsequent Business Scandals Colin Boyd Journal of Business Ethics ISSN 0167-4544 Volume 106 Number 3 J Bus Ethics (2012) 106:283-293 DOI 10.1007/s10551-011-0995-6 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be selfarchived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your work, please use the accepted author’s version for posting to your own website or your institution’s repository. You may further deposit the accepted author’s version on a funder’s repository at a funder’s request, provided it is not made publicly available until 12 months after publication. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Bus Ethics (2012) 106:283–293 DOI 10.1007/s10551-011-0995-6 The Nestlé Infant Formula Controversy and a Strange Web of Subsequent Business Scandals Colin Boyd Received: 25 April 2011 / Accepted: 7 August 2011 / Published online: 21 August 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011 Abstract The marketing of infant formula in third-world countries in the 1970s by Nestlé S.A. gave rise to a consumer boycott that came to be a widely taught case study in the field of Business Ethics. This article extends that case study by identifying three specific individuals who were associated with managing Nestlé’s response to that boycott. It reveals their subsequent direct involvement in a number of additional ‘‘classic’’ 1980s business scandals (some of which ended with major criminal trials and the imprisonment of eminent business figures)—and describes tangential linkages to other business scandals of the time. The article discloses a behind-the-scenes pattern of business villainy, adding both depth and breadth to previous accounts of these scandals. The article offers a conceptual framework that goes beyond personal greed as an explanatory factor for such unethical behavior in the business world, suggesting the presence of personal and organizational networks of intrigue and opportunity. The linkages between the scandals suggest an epidemiological process with the plotters acting as ‘‘virus’’ carriers contaminating various corporate cultures. Introduction Keywords Beech-Nut Drexel Burnham Ernest Saunders Guinness Infant formula Insider trading Nestlé Although Nestlé was the subject of the boycott, the infant formula controversy may have initially been seen more as a dispute over generic bad practices within the infant formula industry rather than as a focused attack on one particular firm, a perspective that Nestlé itself may have wanted to engineer. The original publication that stimulated the boycott refers to an industry-wide pattern of marketing of infant formula. (Muller 1974) To begin with Nestlé was illustrative of an overall malaise, and it is conceivable that if it had not been the industry market leader then social activists might have initially focused their attacks on an alternative firm in the industry. Nestlé was ‘‘the unwilling representative of the entire formula industry’’ (Frederick et al. 1992, p. 563). C. Boyd (&) Department of Management and Marketing, Edwards School of Business, University of Saskatchewan, 25 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5A7, Canada e-mail: boyd@edwards.usask.ca The field of Business Ethics relies on a relatively small core of well-known cases of corporate behavior to illustrate the themes of the subject. Near the top of this list of familiar names (e.g., the Ford Pinto, Tylenol, and Bhopal) is Nestlé S.A., the Swiss food conglomerate. Of all the business histories examined by students of ethics, Nestlé’s saga of controversy is perhaps one of most intriguing. In the late 1960s, Nestlé was criticized by social activists for its marketing of powdered milk formula for infants in less developed countries. The case became a cause ce´le`bre as Nestlé became the victim of a well-organized boycott campaign. The conflict has become a popular case study in the business school curriculum because it demonstrates the need that companies have to constantly preserve and enhance their legitimacy in the public eye. The discussion of legitimacy leads quite naturally into a discussion of issue management, and the consequences of mismanaging a public issue (Post 1985 p. 127). 123 Author's personal copy 284 The Nestlé boycott evolved to be essentially impersonal, therefore. It came to be directed at Nestle as an evil collective corporate entity rather than at specific named managers as particular villains within Nestlé, individually responsible for Nestlé’s corporate actions. Even if there had been individual identifiable villains within Nestlé’s senior management it was considered unlikely that their unethical behavior would continue after the boycott because of the need for pragmatism: The corporate culture at Nestlé has been profoundly affected by ten years of conflict and a seven year product boycott. Employee turnover and morale is known to have been affected, and management attention to the boycott has cost the company dearly in terms of other business needs and decisions. One factor that encouraged the company to act to end the boycott is that Nestlé’s new senior management has wanted to turn from this issue to other, more pressing business problems (Post 1985, p. 124). This article explores the ethical conduct of Nestlé and some of the firm’s senior managers in those years following the infant formula controversy. A priori, Nestlé would be expected to seek and achieve a reputation of good conduct in the aftermath of the controversy, if only to avoid the glare of further adverse publicity. Unfortunately, the history of Nestlé’s direct and indirect involvement in some major business scandals in the 1980s, as revealed below, suggests that some senior managers of the firm were irredeemably unethical. Nestlé’s role in these further scandals leaves little doubt as to the historical origins of the infant formula scandal—Nestlé had a continually defective culture at the most senior level of management. This article attempts to extend our knowledge of the Nestlé infant formula controversy by naming specific unethical individuals within Nestlé. Their influence on Nestlé’s overall behavior has been previously overlooked, as if there were no one who had been behind the steering wheel causing Nestlé to behave the way in which it did. The article opens with a brief review of the infant formula controversy, and then describes the recruitment of Ernest Saunders to Nestlé. He was put in charge of negotiating the end of the Nestlé consumer boycott. He became head of a division of Nestlé that then acquired the US baby food firm, Beech-Nut Nutrition. This firm was subsequently fined for selling fake apple juice for babies, and its senior executives sentenced to jail. The article describes how Ernest Saunders left Nestlé to become head of the UK brewing firm Guinness, appointing his friend Arthur Fürer, the Chairman and Managing Director of Nestlé, to be a director of Guinness. Another director he appointed was Tom Ward, a US legal 123 C. Boyd consultant to Nestlé who had worked with Saunders and Fürer on the baby-milk case, and who had also been BeechNut’s attorney. After engineering a takeover of one Scotch whisky firm, Saunders later consulted with Ward and Fürer over the possibility of Guinness taking over the giant UK firm of Distillers Ltd, the major player in the Scotch whisky industry. The takeover, which involved a share swap, eventually succeeded and was the largest ever takeover in British business history at that time. However, as a result of subsequent revelations by Ivan Boesky, the convicted insider trader, Saunders was later jailed for stock manipulation in the Guinness takeover of Distillers. Ward was prosecuted for theft. A major participant in the Guinness stock manipulation scheme was Bank Leu, a Swiss bank coincidentally chaired by Arthur Fürer. The article further relates how Dennis Levine, the disgraced insider trader from Drexel Burnham Lambert, came to route all his illegal trades through Bank Leu. This set of scandals involves many of the most infamous episodes in the history of business in the 1980s, some of which ended with major criminal trials and the imprisonment of eminent business figures. At the core are three individuals from Nestlé who were involved in negotiating the end of the Nestlé boycott. The article concludes with an analysis of the possible causes of the clustering of this constellation of business scandals around the Nestlé Fürer– Ward–Saunders nexus. A Venn diagram showing the relationships between these scandals is shown in Fig. 1. The final section of this article examines a tangential phenomenon illustrated in the diagram, the predation of firms which themselves had suffered from scandals. Thus, the article describes further links to the Thalidomide tragedy, the Bhopal disaster, and the Perrier product recall. Ernest Saunders and the Infant Formula Controversy Nestlé, the Swiss food conglomerate, was subject to consumer boycotts in the 1970s because of its marketing of powdered milk formula for infants in less developed countries. Free samples were distributed at maternity units, and by sales representatives dressed as quasi-medical personnel. The criticism was that third-world mothers were being persuaded that infant formula was better for their babies than breast milk. Once a mother switches to powdered milk and stops breast feeding her baby, her production of milk ceases, and the supplier has a locked-in customer. (For fuller descriptions of the infant formula controversy, see Murray 1981; Bucholz et al. 1985; Post 1985; Mokhiber 1988; Kuhn and Shriver 1991; Frederick et al. 1992; Sethi 1994.) Author's personal copy A Strange Web of Business Scandals 285 Fig. 1 A Venn Diagram of business scandals and relationships. The central scandals are encircled in bold. The dotted oval indicates a business relationship. The individuals with underlined names were subjected to criminal prosecutions Critics of Nestlé argued that persuading mothers to switch to formula feeding could cause infant deaths in three ways: 1. babies were unprotected against illness because they did not receive the essential antibodies contained in breast milk; 2. mothers were either ignorant of the need to use sterilized water, or could not afford to boil water, and thus prepared infant formula with contaminated water, and; 3. mothers could not afford the price of the product and saved money by diluting the amount of formula in each feed, causing malnutrition. The boycott of Nestlé began in the United States in mid1977. Ernest Saunders had joined Nestlé in Switzerland in 1976, after a career in the United Kingdom in consumer goods marketing and retailing. His involvement with the infant formula controversy was initially one of damage control: At Nestlé, Saunders was assigned the task of countering the criticism raised by the World Health Organization (WHO) against the company’s heavy marketing of its powdered milk to the Third World….Saunders mounted a campaign using public relations and the media in an attempt to swing public opinion. On Nestlé’s behalf he sent $25,000 to a Washington research centre to finance the commissioning of a Fortune magazine article opposing the WHO campaign. The article was unsuccessful, confirming rather than allaying suspicions, and engendered more bad publicity (Kets de Vries 1988, p. 4). Part of Nestlé’s strategy to handle WHO criticism was to advocate an industry-wide response. Nestlé worked closely with the International Council of Infant Food Industries (ICIFI), the industry’s self-regulatory organization. Ernest Saunders was eventually elected to the presidency of ICIFI, initiating a process of negotiation with WHO that led to the ending of the boycotts in 1984 (Saunders 1989, p. 48).1 According to Post (1985, p. 121), the boycott of Nestlé could have ended in mid-1981 rather than in 1984 if the Reagan Administration had not voted against the WHO code in 1981, thus making the US the sole opponent of the code and stimulating further consumer agitation. Ernest 1 This information comes from James Saunders’ book about his father, Nightmare: the Ernest Saunders Story. The genesis of this book, published prior to Saunders’ trial in the Guinness stock manipulation case, is described in ‘‘Ernest Saunders Markets His Innocence,’’ Business Week, Aug. 14, 1989, pp. 92–93. Although the book is patently self-serving, there is no reason to doubt the validity of the record of background facts from the book that are selectively quoted within this article. 123 Author's personal copy 286 C. Boyd Saunders thus came close to defeating the boycott before his departure from Nestlé in late 1981. Saunders was assisted in these negotiations by Tom Ward, a long-standing external legal consultant to Nestlé’s US office: ‘‘Ward had… strong political connections in Washington, and a skill for negotiating difficult political issues. That was how Ernest first met Ward, who was also working closely with Dr. Fürer, the managing director [of Nestlé], on Washington-related measures’’ (Saunders 1989, p. 47). Ward continued his involvement in the WHO negotiating process for Nestlé after Ernest Saunders left to join Guinness. Dr. Arthur Fürer, a Swiss financial expert, had started working for Nestlé in 1954. He became Nestlé‘s chief executive officer in 1975 and was the chairman of Nestlé’s board of directors from 1982 to 1984 (Heer 1991, p. 374). The initial relationship between Ernest Saunders and Thomas Ward is elsewhere described as follows: ‘‘Saunders had first used his [Ward’s] talent for protecting trade marks when he was at Nestlé—there is some suggestion he helped out Saunders in the Baby Milk Scandal in the US— and he had later used Ward at the Bell’s bid [at Guinness]’’ (Kochan and Pym 1987, p. 107). Saunders was evidently heavily involved in cleaning up the mess from the baby milk controversy for Nestlé. However, this was not his main role with his new employer—one of Saunders’ principal assignments at Nestlé was the establishment of a products group in nutritional marketing to meet the anticipated demand for healthier eating (Kets de Vries 1988, p. 3). His success in developing nutritional marketing led to his appointment as head of Nestlé’s Specialist Nutrition and Infant Products Group. According to his son, the product group’s task was to improve and broaden the range of nutritional products for the so-called vulnerable groups within the population— babies, the elderly and those with specific nutritional deficiencies (Saunders 1989, p. 45). One of Ernest Saunders’ Division’s subsidiaries was the US baby food company, Beech-Nut Nutrition, acquired by Nestlé in 1979. Beech-Nut was still a strong brand name, its most profitable divisions (such as the famous chewing gum division) had long been sold off. The firm was reduced to a barely profitable single product, baby food, with a small share of a market dominated by Gerber Products. Nestlé bought Beech-Nut for $35 million in 1979. The Beech-Nut subsidiary became a part of Ernest Saunders’ Specialist Nutrition and Infant Products Group. This link between Ernest Saunders and Beech-Nut has not been strongly highlighted before.3 Nestlé’s ownership of Beech-Nut has been widely noted, but the fact that Saunders, Ward and Fürer are the human link between the full set of three controversies (Nestlé, Beech-Nut, and Guinness) has not been previously disclosed.4 In accord with Saunders’ mandate to develop a nutritional marketing thrust in his group, Nestlé spent millions of dollars to revamp Beech-Nut’s marketing approach and to modernize manufacturing facilities. In 1980–1981, Beech-Nut lost $2.5 million on sales of $62 million. In April 1981, Neils Hoyvald, a native of Denmark who had joined the firm in 1980, was appointed to be Beech-Nut’s president. In September 1981, Saunders himself left Nestlé to take over the running of Guinness in London. Saunders was thus the Nestlé executive responsible for Beech-Nut between its acquisition in 1979 and his departure in September 1981. Saunders almost certainly was involved in appointing Hoyvald to the senior position in Beech-Nut. Was Saunders directly or indirectly responsible for the sensational scandal at Beech-Nut that was later uncovered, a scandal that resulted in jail sentences for Hoyvald and his deputy? Considering the scale of Nestlé’s investment, and the poor financial results, there must have been intense Swiss pressure for an improvement in BeechNut’s performance. The Acquisition of Beech-Nut 3 Beech-Nut was founded in the United States in 1891 as a firm selling beech wood-smoked bacon and ham. It had a strong corporate culture founded on its trademarks of purity, high quality, and natural ingredients.2 Although 2 This abbreviated version of the Beech-Nut story is derived from the following press articles: Welles (1988); ‘‘OJ Wasn’t 100% Pure, FDA Says,’’ USA Today, July 26, 1988, p. A1; Queenan (1988); Consumer Reports (1989); Freedman (1989); Wong (1989); Monks and Minow (1989). See also Boyd (1992, 1996). 123 The Fake Apple Juice Scandal In 1977, Beech-Nut had started buying apple juice concentrate from a wholesaler whose prices were 20% below market. Beech-Nut saved around $250,000 a year by A 1991 search of Reuters Textline service revealed that in the UK press, for example, there was only one short reference linking the Guinness scandal to Nestlé’s baby-milk controversy, printed in the Evening Standard (London), Jan. 16, 1987, p. 54. Also, there was but one short piece in the UK press linking Ward to the Beech-Nut scandal, printed in The Observer, Feb. 28, 1988, p. 33. 4 There were rumors about Saunders’ past at the time of the contested bid for Distillers, but this private mud-slinging seemed exclusively directed at his involvement in the Nestlé baby-milk controversy: ‘‘Unsolicited approaches were also made to Argyll with offers of information about Guinness. There were many allegations about Saunders’ career at Nestlé and the baby milk scandal’’ (Kochan and Pym 1987, p. 127). Author's personal copy A Strange Web of Business Scandals buying from this source. There were rumors of apple juice adulteration in the industry, but there was no official government test for apple juice purity. Beech-Nut’s Director of R&D, Jerome J. LiCari, was suspicious of the low price charged by the juice supplier. On August 5, 1981 he sent a memo to senior executives voicing his fears about Beech-Nut’s supplier of apple juice concentrate. He called for a top-level meeting to evaluate his evidence of adulteration. When he got no response, LiCari went to Beech-Nut’s new president, Neils Hoyvald, to present his case against the supplier. LiCari left with the impression that Hoyvald would react. Several months later LiCari resigned his position because of the lack of response to his complaints. He later blew the whistle to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Although Hoyvald was not at Beech-Nut when the apple juice adulteration started, he had an opportunity to come clean at the point when the FDA started investigating: ‘‘Beech-Nut could have avoided scandal at this point by conceding that its juice was sugared water’’ (Consumer Reports 1989, p. 295). Instead, Beech-Nut brazenly defied the FDA, blocking the investigation while trying to sell off stocks of bogus juice as fast as possible. Beech-Nut ran a special promotion—‘‘buy 12 jars of baby food and get six jars of fruit juice free,’’ and exported the juice to Caribbean countries outside the jurisdiction of US food and drug laws. Hoyvald’s attitude is clear in a memo he wrote to Nestlé, boasting about the $3.5 million he had saved by obstructing the FDA’s recall of apple juice products: It is our feeling that we can report safely now that the apple juice recall has been completed. If the recall had been effectuated in early June, over 700,000 cases in inventory would have been affected…. due to our many delays, we were only faced with having to destroy approximately 20,000 cases (Consumer Reports 1989, p. 296). Hoyvald was subsequently sentenced to 1 year and a day in jail, and fined $100,000 for selling bogus children’s apple juice.5 The juice was revealed to be a mixture of beet 5 Hoyvald later made a successful appeal against his sentence, on the grounds that the case had been tried in the wrong jurisdiction. The author is unable to determine the subsequent disposition of this case. Ethics professors may be intrigued by the fact that in the original trial Hoyvald’s lawyer, Brendan Sullivan, proposed that his client should teach ethics seminars in colleges rather than serve time in prison. In his Barron’s article ‘‘Juice Men: Ethics and the Beech-Nut Sentences,’’ Joe Queenan takes a satirical look at the consequences of Hoyvald teaching ethics, had it occurred. He quotes imaginary ethics professors who fear for their jobs in competition with big-time crooks. In this scenario, he suggests that the classes might be filled with students trying to learn unethical behavior firsthand! (Queenan 1988) 287 sugar, apple flavor, caramel coloring, and corn syrup, despite a label proclaiming it to be 100% pure. Beech-Nut itself was fined $2 million, six times the sum of the largest previous FDA fine. The firm also settled a class-action suit for $7.5 million. Guinness and the Nestlé Connection In September 1981, Saunders resigned from Nestlé to run the brewing firm Guinness in London. He quickly revived sagging sales of the company’s flagship stout beer with heavy expenditures on sophisticated ads. He disposed of various peripheral businesses and initiated a set of strategic acquisitions. In 1985, Guinness made a successful hostile takeover bid for Arthur Bell & Sons, a mid-size Scotch producer. As noted above, Tom Ward advised Guinness on the bid. Later that year, the Argyll Group made a bid for Distillers, a conglomerate that was the largest producer of Scotch whisky. Saunders did not wish to have this competitor slip into Argyll’s hands, and he contemplated making a rival bid for Distillers. If successful, the £2.3 billion takeover of Distillers would become the largest in British history. Saunders was uncertain about making a bid, and he sought the advice of friends, including Dr. Arthur Fürer, his former boss at Nestlé and now it’s Chairman. At the time of the Distillers takeover Fürer was also the Chairman of the fifth-largest Swiss bank, Bank Leu (pronounced Loy, as in toy.), In 1984, Saunders nominated Fürer for appointment to the Guinness board of directors, thus formalizing his link with the Nestlé supremo. Saunders later nominated Thomas Ward, his other long-time colleague from Nestlé, for appointment to the Guinness board in January 1985. Saunders’ son’s book describes a discussion at Christmas 1985 between Saunders, Ward and Fürer prior to the launching of the Guinness bid for Distillers: Tom Ward came over with his family. With their wives, the two of them met Arthur Fürer for dinner at the Montreux Palace. As is the custom in Switzerland, after dinner the wives were ushered away into a corner while the men talked. The size of the Distillers bid did not seem particularly spectacular to Fürer, for Nestlé was itself huge. He was enthusiastic. Ernest said: Fürer talked about what he saw as the necessity for getting Guinness shares quoted on the world’s stock markets if we were to be a worldscale company. I could see the glint in Fürer’s Footnote 5 continued For a further odd twist on this theme, see footnote 6, which discloses that an unrepentant Ernest Saunders was invited to lecture about ethics to business school students after his bizarre release from jail. 123 Author's personal copy 288 C. Boyd eye. Bank Leu, where he was a director, could be put on the map by becoming the Swiss lead bank in an international stock market listing programme, which did later happen. by Bank Leu… and, in apparent breach of the Companies Act, a Guinness subsidiary deposited £50 million with a Luxembourg subsidiary of Bank Leu (Times 1987, p 21). So, like many others involved in the battle, Fürer’s enthusiasm had other motives. Ward was also very positive about the idea… (Saunders 1989, p. 143). Bank Leu accepted the facts in Macfarlane’s statement, but denied any illegality. When the board dismissed Saunders, it also asked for the resignations of Ward and Fürer from the Guinness board: both refused. Fürer insisted that he had not behaved wrongly; he claimed to have been totally unaware of the transactions that Guinness had asked Bank Leu to carry out (Times 1987, p. 21; Putka 1987). Under intense pressure, Fürer resigned the next day. Ward was also forced off the board and was served with a writ from Guinness asking for the return of a £5.2 million fee paid in the name of Marketing and Acquisition Consultants after the successful Distillers takeover bid. Ward controlled this firm, and £3 million of this fee was later transferred to a secret Swiss bank account held by Ernest Saunders. Ward was subsequently charged with the theft of this fee from Guinness, and fought a long battle to prevent his extradition from the US to face this charge. He eventually appeared in a British court in January 1993, where he was found not guilty of theft after a 5 week trial. Despite their close links to Saunders and the stock manipulation scheme, neither Arthur Fürer nor Bank Leu was prosecuted in Britain. Ernest Saunders, the Chairman and Chief Executive of Guinness, was charged with theft, conspiracy, false accounting, and violations of the Companies Act. In 1990, he was sentenced to 5 years in jail. An eminent British tycoon, Gerald Ronson, was also sentenced to a year in jail in the same trial for his part in the stock manipulation. He had met with Saunders and Ward in April 1985, and had put up a stake of £25 million as part of the Guinness ‘‘fan-club members’’ share support scheme (Ronson and Robinson 2009, p. 119). Saunders was subsequently released from prison early on medical grounds after serving only 10 months of his jail sentence. This apparently humanitarian gesture (he was diagnosed as suffering from Alzheimer’s disease) drew intense criticism in the light of Saunders’ later behavior. Here is a typical quotation from the satirical British journal Private Eye: The book by Saunders’ son is clearly biased in its reconstruction of the history of the Guinness bid for Distillers. The book makes no further mention of Bank Leu, and yet Bank Leu was the largest player in the stock manipulation scheme that was initially revealed by the disgraced arbitrageur Ivan Boesky in his plea-bargaining confessions to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (Kirkland 1987; Kay 1987). Following Boesky’s tip-off, the UK Department of Trade and Industry investigated the takeover of Distillers Ltd. by Guinness plc. They discovered that Guinness had orchestrated and underwritten an international buying campaign that artificially inflated the value of its shares during the fierce battle for Distillers. The Guinness offer was largely a swap of its shares for Distillers, so that when the value of Guinness shares rose in the market, the number of shares it had to offer to buy Distillers was reduced. This scandal was a major embarrassment for London’s financial community and was intensely followed by the media. Besides Boesky (later jailed for 3 years for insider trading), and various Guinness executives, the others involved were a group of leading British business executives, stockbrokers, and financiers. Trials and jail terms for some of these individuals followed. The media largely overlooked the roles of Arthur Fürer and Bank Leu in the scandal, partly perhaps because of the spectacular prominence of these other players. Bank Leu’s involvement in the stock manipulation scandal was revealed in a letter to Guinness shareholders from Norman Macfarlane, who was appointed acting Chairman of Guinness following Saunders’ dismissal by the board in January 1987. Macfarlane’s letter reveals a $100 million investment by Guinness in a fund run by Ivan Boesky, and describes unlawful indemnities given to Bank Leu by former Guinness directors. The letter said: A number of serious disclosures have been made to the board. It has been established that substantial purchases of Distillers and Guinness shares were made by wholly-owned subsidiaries of Bank Leu AG on the strength of Guinness’s agreement to repurchase the shares at cost plus carrying charges—an agreement which, at least as regards its own shares, Guinness could not have legally fulfilled. It is also alleged that these purchases may have been financed 123 I am delighted to see my old friend Deadly Ernest Saunders, the convicted fraudster, alive and well at a House of Lords cocktail party. He is typically modest about making medical history by being the only man ever to reverse the onset of senile dementia—a complaint which, you may recall, procured his early release from Ford prison (Private Eye 1992).6 6 Other negative press comment included ‘‘Saunders Shows off Powers of Recovery,’’ Sunday Times, Apr. 26, 1992; ‘‘Return to Author's personal copy A Strange Web of Business Scandals If his recent book, Gerald Ronson indicates that it was he who suggested faking dementia to Saunders when they were first serving time in jail together. Ronson recollects saying the following to Saunders: If you made out that you’ve got Alzheimer’s, nobody could ever prove it, because if they looked inside your head, what are they going to find?…. It wouldn’t be difficult for you, because, besides being a psychotic liar, you are mentally deranged (Ronson and Robinson 2009, p. 154). Ronson can also viewed making almost the same comment (‘‘It shouldn’t come hard for you, because you are a psychotic liar…’’) on a YouTube video clip posted by his co-author (YouTube 2009). These damning comments leave us in no doubt that Ronson, for one, was of the opinion that Ernest Saunders was completely unethical. As an aside, the Venn diagram shown above reveals a further networking relationship between two of the individuals involved in these scandals. When Gerald Ronson was released from jail, his ailing business empire (Heron International) was rescued from financial failure by former junk-bond king Michael Milken (Bill 2009; Ronson and Robinson 2009 pp. 181–187). Milken himself was not long out of jail for participation in the insider trading scandals described in the next section. Ronson also claims to have been the person who connected Saunders and Ward to Ivan Boesky in the first place: I admit, though, that I was the one who gave them Boesky’s phone number. Saunders told me that Thomas Ward wanted to meet Boesky and asked me if I knew him. As it happened I had his number [and] my secretary passed the number on to Ward. (Ronson and Robinson 2009, p. 121). Bank Leu and the Insider Traders Meanwhile, Bank Leu was coincidentally the bank chosen by Dennis Levine, a former managing director of Drexel Burnham Lambert7, to be the offshore bank that would Footnote 6 continued Health and Wealth,’’ The Times, Mar. 14, 1992; ‘‘So, Just How Ill Were They?’’ Daily Telegraph, Mar. 10, 1992; and ‘‘Looking For Work In Earnest—Ernest Saunders Enjoys New Lease Of Life,’’ Independent, Feb. 21, 1992. Saunders later defiantly appeared before an audience of business school students to give his version of the Guinness story—see ‘‘Ernest Saunders In Ethics Talk To Students’’ Daily Telegraph, Mar. 17, 1992. 7 Strangely, given the magnitude of prior press coverage in the UK, there is no mention of the Guinness scandal or of Bank Leu in The Predators’ Ball, the best-selling US book about ‘‘The Inside Story of Drexel Burnham Lambert’’ (Bruck, 1988). 289 handle all of his insider trades. In his subsequent book about his criminal activities Levine tells of first using a branch of one Swiss bank in the Bahamas. This bank soon refused to handle his questionable stock trades, forcing him to select another. He describes his choice of Bank Leu: When I arrived (in Nassau)…I flagged a cab and headed for Bay Street. I simply stopped at a phone booth and looked up banks in the local version of the Yellow Pages. The first ad to catch my eye was that of Bank Leu International Ltd. It was described as a wholly owned subsidiary of Bank Leu Ltd. Zurich (Switzerland), the oldest private Swiss bank, founded 1755. Among its listing of services offered was International Portfolio Management. I located the office in the Bernard Sunley Building in Rosen Square and walked in (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 23). Levine soon became Bank Leu’s biggest customer in the Bahamas, using public telephones and code names to communicate his trading instructions. The bank branch and its Swiss headquarters, according to Levine, were fully cognizant of the nature of his trades and of the need to conceal them from detection. Following an SEC inquiry into one particular trade executed by Bank Leu’s New York brokers, there were conversations about Levine’s trades between the branch and Switzerland: … [The bank]… concluded that there was no problem with my trading, even if it was based upon inside information, because it was not a violation of Bahamian law. Nonetheless, [Switzerland] advised caution. Following this, Fraysee [the branch manager] ordered that several new brokerage accounts be opened at various offices in the US. This was a defensive measure to spread my transactions around other brokers and was a clear indication that Bank Leu valued my business and wanted to ensure its continuity (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 117). Unknown to Levine, the SEC later got on his trail not because of his own trades, but because of the greed of the staff in Bank Leu. They had noticed the success of his trades, and began piggybacking on Levine’s trades. His recollection of a confrontation with Bank Leu’s personnel explains their actions: ‘Let me get this straight’, I said, feeling the level of my voice rise. ‘I place an order for stock. Now I am discovering that not only were my orders filled, but you bought the same stocks for your personal accounts and for other accounts here at the bank, and then your brokers in New York bought for themselves and other people.’ 123 Author's personal copy 290 They had a cottage industry going here! They had piggybacked my trades and magnified the effects in markets around the world. I gulped and asked, ‘Well, how many of your so-called managed accounts did you make these trades in?’ ‘Twenty-five or thirty.’ ‘Oh, my God! And you did most of this through one broker?’ Meier nodded (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 239). Levine was clearly appalled at the ethics of the Bank Leu managers, or, at least, by their amateurishness. The relative lack of concealment of these personal orders allowed the SEC to trace their source back to the Nassau branch of Bank Leu. During this SEC investigation, Bank Leu offered to further conceal Levine’s activities within a set of phony managed accounts. Bank officers told Levine that the Bahamian and Swiss bank secrecy laws would protect his anonymity: ‘‘… [They]… all assured me that the Bahamian secrecy defense as well as the managed accounts defense had all been approved by their superiors in Zurich’’ (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 252). Levine’s reliance on Swiss and Bahamian secrecy laws was misplaced, for it was Bank Leu itself that finally revealed his identity to the SEC when the pressure of the investigation became too strong. Levine expresses his dismay at what he regarded as an unconscionable act of betrayal: ‘‘It was the first time in history that a Swiss or Bahamian bank had agreed to such a clear and willful violation of secrecy laws in order to protect itself’’ (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 289). Levine was eventually jailed for 2 years. One of his insider partners was Ivan Boesky, who made $50 million from Levine’s inside tips (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 304). Both Levine and Boesky shared information with Michael Milken, himself later jailed for insider trading. Perceiving himself to be a victim of an unscrupulous Swiss bank, Levine adds an indignant postscript to the Wall Street insider trading scandal when he refers to the Guinness–Distillers–Boesky–Bank Leu scandal in his book: ‘‘I found diabolical pleasure in learning that Bank Leu AG of Switzerland was the major co-conspirator, involved in half the purchases’’ (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 363). C. Boyd structural factor is that of business secrecy, specifically the secrecy laws of Swiss banks (now largely eliminated) and of off-shore financial centers such as the Bahamas. It is obvious that individuals intent on unscrupulous or illegal business acts will seek the maximum amount of camouflage to disguise their activities. Industries or countries with secrecy rules offer the most attractive haven for the conduct of unethical business practices. It should not be surprising, therefore, to discover that a group of prominent business scandals are clustered together, adjacent to environments that offer the greatest concealment of this scandalous behavior. The second conjecture relates to the Swiss connection between the set of scandals. Is there something pathological about Swiss business culture that differentiates the conduct of Swiss firms from that of other Western-based firms? There are other cases of notorious conduct in modern Swiss business history; most notably involving the pharmaceutical firm Hoffman-La Roche. That firm had been implicated in two major prior scandals. The first involved excessive pricing of the patented prescription drugs Librium and Valium. In a succession of countries the firm was investigated for charging up to $4,000 a kilogram for raw materials that were shown to cost around $25 a kilo to manufacture in Italy, where drugs were not protected by patents (see Monopolies Commission 1973; Constable 1979). The second scandal involved the revelation to the European Economic Community (EEC) of Hoffman-La Roche’s control and manipulation of the world market for vitamins. Stanley Adams, a senior La Roche executive, blew the whistle to the EEC before leaving the firm and moving out of Switzerland.8 Adams provides some critical comments on Swiss business culture in his description of his decision to blow the whistle: I was a foreigner, which probably helped. I had not been brought up under the Swiss System with the belief that corporate loyalty is inviolable at all times, and that what the company does must be good, because your welfare is dependent on the company’s welfare, and the company’s welfare is dependent on the welfare of all companies put together, and the chain may not and cannot be broken without grave 8 The Relationship Between the Scandals What are the possible reasons for the grouping of this set of scandals? There are several conjectures that can be made. The first is related to the structure of the context—is there is something inherent in the structure of the business environment that links this set of scandals? The most obvious 123 Stanley Adams suffered enormously as a result of blowing the whistle on Hoffman-La Roche. The EEC failed to keep his identity secret, and he was arrested when he re-entered Switzerland to visit his wife’s relatives on New Year’s Eve, 1984. He was charged with industrial espionage. He was released from custody 3 months later, following his wife’s suicide. She had apparently been misled by police into thinking that he would receive a sentence of 20 years imprisonment. He later successfully sued the EEC for the damages caused by their failure to protect his anonymity. Author's personal copy A Strange Web of Business Scandals consequences to all concerned. To me, business was just business. It could be moral or immoral, depending on the way individuals chose to conduct it, and if the good of the company demanded ruthless suppression of the individual or the smaller businesses, then there was something wrong (Newbigging 1986: based on Adams 1985). From the understandably jaundiced perspective of Adams it seems reasonable to infer that the web of scandals might have some basic origin in a perverted sense of Swiss corporate loyalty. Can the behaviors of Nestlé, Bank Leu, and Hoffman-La Roche be extrapolated to be indicative of Swiss business culture as a whole? In the absence of evidence of similar behavior by other firms such a strong conclusion seems unjustified. The third conjecture pertains to culture, and the manner in which deviant corporate cultures might transmit their influence to other corporate environments. If it is theorized that Nestlé had a corporate culture that tolerated unethical business practices in the 1970s, then the evolution of the BeechNut, Guinness, and Bank Leu scandals are all explicable as infections emanating from a rotten core culture. This theory of transmission of tolerance or even encouragement of unethical acts from one corporate culture to another is essentially an epidemiological theory. The analogy between the transmission of disease and the transmission of evil is implicit in some of the metaphors used to describe unethical behavior—the ‘‘rotten apple in the barrel’’ must be removed if the rest of the population is to survive untainted. If the set of scandals described above are linked by epidemiology, then the transmission of the disease from the Nestlé culture to the Beech-Nut culture to the Guinness culture was clearly attributable to the networking efforts of one or more of the three central characters in this story: Ernest Saunders, Arthur Fürer, and Thomas Ward. There is evidently something more than just randomness in the intersections between the scandals. Levine’s association with Bank Leu, for example, was not exactly random. He was rebuffed by one Swiss bank (thus discrediting any theory that Swiss business culture is distorted), so he went and found another. He just happened to have the good fortune to find Bank Leu on his second try, while looking in a place where unethical trading was more likely to be tolerated. Levine searched for a structural defect that would support his lust to profit by his inside knowledge. Protected by the structure of secrecy, the willing supplier was a Swiss bank, chaired by an individual whose other directorships included firms that indulged in questionable business practices. The nexus is that in part of the Swiss business community there was a source of unethical behavior which 291 infected several other corporate environments which, in turn, when shielded by a structure of secrecy attracted the activities of other unethical individuals. The original source was the corporate culture of Nestlé: it is evident that the original Nestlé infant formula controversy needs to be reconsidered in the light of this subsequent succession of related scandals. A Postscript Thalidomide, Bhopal, and Perrier: The Vulnerability of the Scandal-Plagued Firm There are several other controversial business events that are less directly linked to the main Nestlé–Saunders– Fürer–Bank Leu axis of scandals described above, but which are of interest nevertheless. Manfred Kets de Vries suggests a fascinating reason why Distillers was an easy target for takeover by Guinness: Perhaps Distiller’s malaise had a more subtle origin than simply poor leadership, competitive pressures or organizational politics. An attempt in the late 1950s to diversify into pharmaceuticals went disastrously wrong. Thalidomide, a sedative frequently prescribed for pregnant women, caused over 8,000 babies to be born with appalling deformities before it was withdrawn. The shock to the management and board was total and affected company morale for nearly a decade as victims fought to gain compensation. To a group of reticent Scottish gentlemen it brought public exposure of the worst kind and a moral conundrum that seemed insoluble. Whether the affair sapped management confidence to the point of inertia is still debated (Kets de Vries 1988, p. 9). The Nestlé–Beech-Nut–Distillers path of encounters in Saunders’ career thus provides a link between firms whose controversial activities involved babies in one way or another. It is heart rending in the extreme to consider that such a vulnerable group in society, for whom we might expect the very highest standards of duty and ethical care, should be the victims of this particular set of scandals. Kets de Vries’ analysis suggests that the sapping of management morale by an ethical scandal induces belowpar performance. The resulting under-valuation of the firm puts it into play as a takeover target. Ironically, Bank Leu itself became a victim of this phenomenon! Dennis Levine takes some self-serving glee in describing the bank’s eventual demise: Reeling from the revelations of its role in my activities and its apparent violation of Bahamian and 123 Author's personal copy 292 Swiss banking laws, coupled with the scandal of its central role in the Guinness affair, Bank Leu sold out to Crédit Suisse in May 1990 (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 411). Another irony emerges from the last macabre insider deal that Levine channeled through Bank Leu. He bought 100,000 shares in Union Carbide for $6.3 million, acting on Michael Milken’s tip to him that Drexel Burnham Lambert was arranging a $3.5 billion financing package to enable GAF Corporation to launch what would turn out to be an unsuccessful bid for Union Carbide. Once again, a corporate disaster put the victim into play, as Levine explains: In December 1984, a leak of poisonous gas from a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, killed more than 2,000 people. Quite apart from the personal horrors, the event was a financial tragedy for the company. One year later, Union Carbide’s stock was still severely depressed, leading GAF, less than onetenth as large, to the decision that it could mount a takeover bid (Levine and Hoffer 1991, p. 271). In yet one more irony, James Sherwin, the Vice-President of GAF Corporation was later charged with stock manipulation when he tried to sell the Union Carbide shares that GAF had acquired as a result of the attempted takeover bid. He was tried three times for this crime, and eventually found guilty and sentenced to 6 months in jail. This verdict was later overturned on appeal. A description of Sherwin’s successive trials appears in his defense attorney’s autobiography (Liman 2002, pp. 250–264), which coincidentally features a description of his later role as Michael Milken’s chief defense lawyer (pp. 265–296). In yet another apparent coincidence Nestlé itself later emerged as the victorious bidder in a takeover battle for Perrier, the French mineral water firm. This takeover aroused intense hostility in France. Nestlé’s bid for Perrier had strong echoes of the takeovers of Distillers and Union Carbide, for Perrier had recently had a corporate catastrophe that made it vulnerable (Economist 1991). In early 1990, traces of benzene were found in samples of Perrier sparkling mineral water. Perrier issued a worldwide recall, only the second global withdrawal of a consumer branded product and the first not to be caused by malicious tampering. There had been a previous takeover by Nestlé which had also produced controversy, and which even linked Ivan Boesky to the baby milk scandal. In 1984, Boesky made his largest-ever insider-dealing profit by speculating in the shares of Carnation Co., the old-line food company. He had learnt that Carnation was about to be taken over by Nestlé in a friendly merger offer (Stewart 1992, p. 171). 123 C. Boyd Nestlé later used Carnation as a vehicle to launch a new brand of infant formula. In a now-familiar scenario, the methods used by Nestlé to market the new Carnation-brand formula in the United States drew criticism from the American Academy of Pediatrics, a body representing 20,000 US pediatricians (Siler 1990). Acknowledgments This article was originally produced in 1992, but unfortunately its path to eventual publication was frustrated at that time. This version is essentially the same as the one initially written, but with updates and revisions provided from post-1992 sources. I wish to thank William C. Frederick (Katz Graduate School of Business, University of Pittsburgh) for encouraging the paper’s resurrection, and for his inevitably wise comments and reflections on the unethical behaviors described in the article. References Adams, S. (1985). Roche versus Adams. London: Fontana Paperbacks. Bill, P. (2009). Never the English Gent: a clear picture of Ronson. Evening Standard (London), June 5. http://www.thisislondon.co. uk/standard-business/article-23704009-never-the-english-gent-aclear-picture-of-ronson.do. Boyd, C. (1992). Beech-Nut Nutrition Corporation (A) & (B) (Cases 392-056-1 & 392-057-1). Cranfield: European Case Clearing House. Boyd, C. (1996). Beech-Nut Nutrition Corporation (A) & (B). In H. Schroeder (Ed.), Cases in business policy. Toronto: Nelson. Bruck, C. (1988). The predator’s ball. New York: Academic Lawyer/ Simon and Schuster. Bucholz, R. A., Evans, W. D., & Wagley, R. A. (1985). ‘Nestlé Corporation: The baby bottle debate. In Management response to public issues: Concepts & cases in strategy formulation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Constable, J. (1979). F. Hoffman-La Roche & Co. AG (Case 183-0568). Cranfield: European Case Clearing House. Consumer Reports. (1989, May). Bad apples: In the executive suite, pp. 294–296. Economist. (1991, Aug. 3). When the bubble burst, pp. 67–68. Frederick, W. C., Davies, K., & Post, J. E. (1992). Nestlé: Twenty years of infant formula conflict. In Business and society: Corporate strategy, public policy, ethics (7th ed., pp. 560–573). New York: McGraw Hill. Freedman, A. M. (1989, July 6). Nestlé quietly seeks to sell beechnut, dogged by scandal of bogus apple juice. The Wall Street Journal, p. B1. Heer, J. (1991). Nestle´: 125 years 1866–1991. Switzerland: Nestlé. Kay, W. (1987, May 18). More trouble brewing: Guinness scandal leads to criminal charges. Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly, 67(20), 44–46. Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (1988). Ernest Saunders: The Guinness affair. Fontainebleau: INSEAD. This original case study was revised, and subsequently published as Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (1990). Ernest Saunders and the Guinness affair (Case 490-014-1). Cranfield: European Case Clearing House. Kirkland, R. I., Jr. (1987). Britain’s own Boesky case. Fortune, 115(4), 85–86. Kochan, N., & Pym, H. (1987). The Guinness affair: Anatomy of a scandal. London: Christopher Helm. Kuhn, J. W., & Shriver, D. W. (1991). A minimal ethic of marketoriented responsibility: The Nestlé case. In Beyond success: Author's personal copy A Strange Web of Business Scandals Corporations and their critics in the 1990s (pp. 216–241). New York: Oxford University Press. Levine, D. B., & Hoffer, W. (1991). Inside out: An insider’s account of Wall Street. New York: Putnam. Liman, A. L. (2002). U.S. v GAF: Good things don’t always come in threes. In Lawyer: A life of counsel and controversy. New York: Public Affairs. Mokhiber, R. (1988). Nestlé. In Corporate crime and violence (pp. 307–317). San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. Monks, R. A., & Minow, N. (1989). The high cost of ethical retrogression. Directors and Boards, 13(2), 9–12. Monopolies Commission. (1973). Chlordiazepoxide and diazepam— A report on the supply of chlordiazepoxide and diazepam. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Muller, M. (1974). The baby killer. London: War on Want. http:// faculty.msb.edu/murphydd/cric/readings/Nestle-Baby-Killer% 20by%20Mike%20Muller,%20War%20on%20Want,%201974. pdf. Murray, J. A. (1981). Nestle´ in the LDCs (Case 383-089-1). Cranfield: European Case Clearing House. Newbigging, E. (1986). Hoffman-La Roche v. Stanley Adams: Corporate and individual ethics (Case 386-007-1). Cranfield: European Case Clearing House. Post, J. E. (1985). Assessing the Nestlé boycott: Corporate accountability and human rights. California Management Review, 27, 2. Private Eye. (1992, Feb. 14). The ‘‘Grovel’’ column, 787, p. 8. 293 Putka, B. G. (1987, Jan. 19). Overseas scandal: Guinness affair makes British likely to curb corporate acquisitions—Unusual stock buying aided firm in its bitter battle to take over distillers—The Ivan Boesky Connection. Wall Street Journal, p. 1. Queenan, J. (1988). Juice men: Ethics and the Beech-Nut sentences. Barron’s National Business and Financial Weekly, 68(25), 37–38. Ronson, G., & Robinson, J. (2009). Leading from the front: My story. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. Saunders, J. (1989). Nightmare: The Ernest Saunders story. London: Hutchinson. Sethi, S. P. (1994). Multinational corporations and the impact of public advocacy on corporate strategy: Nestle and the infant formula controversy. Boston: Kluwer. Siler, J. F. (1990, Apr. 9). The Furor over formula is coming to a boil. Business Week, pp. 52–53. Stewart, J. B. (1992). Den of thieves. New York: Touchstone. The Times. (1987, Jan. 16). Guinness Ousts chairman, 2 directors in stock scandal, p. 21. Welles, C. (1988, Feb. 22). What led Beech-Nut down the road to disgrace. Business Week, pp. 124–128. Wong, B. (1989, March 31). Conviction of Nestlé unit’s ex-president is overturned on appeal in juice case. The Wall Street Journal, p. B5. YouTube. (2009). Gerald Ronson on Ernest Saunders & Alzheimer’s (see statement at 1.00 minute point), at http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=eeRuwKaKzsI. 123