Early Child Development in Social Context: A Chartbook

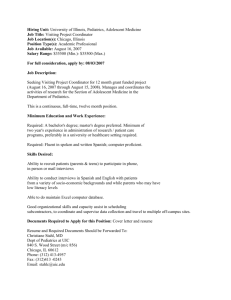

advertisement