Volume 15, Number 02, July 1993

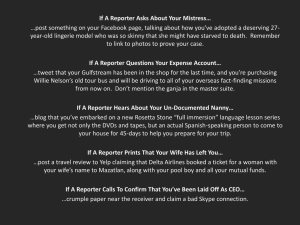

advertisement