Scottetal 10 11 2015 .docx - Cliniques d'Évaluation et de Réadaptation

advertisement

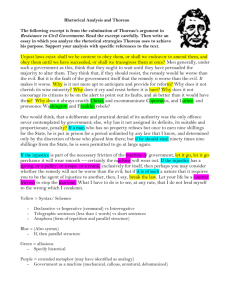

Sources of Injustice Sources of injustice among individuals with persistent pain following musculoskeletal injury Whitney Scott, PhD Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience King’s College London London, UK Amanda McEvoy, BSc Department of Psychology Carlton University Ottawa, Canada Rosalind Garland, BSc Ingram School of Nursing McGill University Montréal, Canada Elena Bernier, BSc Department of Psychology McGill University Montréal, Canada Maria Milioto, PT Centre d’ Évaluation et de Réadaptation de l’Est Montréal, Canada Zina Trost, PhD Department of Psychology University of Alabama Tuscaloosa, USA Michael Sullivan PhD Department of Psychology McGill University Montréal, Canada Corresponding Author: Dr. Michael Sullivan. Department of Psychology, McGill University. 1205 Doctor Penfield Avenue, Montreal, Quebec, H3A1B1. Phone: 514-398-5677; Fax: 514 398-4896; Email: michael.sullivan@mcgill.ca. 1 Sources of Injustice Acknowledgements:This research was supported by funds from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, le Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, and l’Institut de Recherche Robert-Sauvé en Santé et en Sécurité du Travail. The authors thank Véronique Boulais and Valérie Malette for their assistance in data collection. The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this research. Key Words: Chronic pain, perceived injustice, rehabilitation 2 Sources of Injustice 3 Abstract Growing evidence supports the negative impact of perceived injustice on individuals’ recovery trajectory following injury. However, little is currently known about sources that might contribute to individuals’ perceptions of injustice in this context. The purpose of this study was to systematically investigate sources of injustice among individuals with persistent pain following musculoskeletal injury. Following completion of the Injustice Experiences Questionnaire (IEQ), participants completed a semi-structured interview during which they were asked to explain reasons underlying their endorsement of IEQ items. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded to categorize the individuals and groups identified as sources of injustice and reasons underlying the identification of these sources. Participants frequently identified employers/colleagues, insurers, healthcare providers, family, significant others, friends, society, and other drivers as sources of injustice. Common reasons discussed by participants for identifying these sources included the contribution of these sources to the initial injury, inadequate assessment or treatment of pain and disability, and punitive responses to participants’ expression of pain. Sex- and injury-related differences also emerged in the identification of sources of injustice. The Discussion addresses strategies that might be useful for preventing the emergence of perceptions of injusticein individuals who have sustained debilitating injuries. Sources of Injustice 4 Introduction Research suggests that individuals may experience feelings of injustice when they suffer undeserved hardship or loss, particularly when this results from the negligent actions of another person(Lind & Tyler 1988; Mikula 1993; Miller 2001). The experience of persistent pain following accidental injury is a likely context within which individuals may experience perceptions of injustice. In addition to ongoing pain, individuals may experience a number of losses, including loss of employment, independence, and leisure activities(Harris, Morley, & Barton 2003; Lyons & Sullivan 1998). To the extent that these losses violate principles of distributive justice, perceptions of injustice are likely to emerge. External attributions of blame for pain and related losses, for example, to the individual perceived as responsible for the injury, may be common and mayfurther contribute to injustice perceptions(Ferrari & Russell 2001; Mikula 2003). A growing body of research suggests that some individuals with persistent pain following injury experience their situation with a sense of injustice. In the context of debilitating injury, perceived injustice has been defined as an appraisal of the severity and irreparability of injury-related losses, unfairness, and external attribution of blame(Sullivan et al. 2008). The Injustice Experiences Questionnaire (IEQ) is a self-report measure assessing these facets of perceived injustice that has been shown to be reliable and valid among individuals with persistent pain following musculoskeletal injury. In addition to items reflecting loss, blame, and unfairness, several items reflect the perceived failure of others to acknowledge the extent of one’s suffering(Sullivan et al. 2008). A number of recent studies indicate that perceived injustice contributes to problematic recovery outcomes following musculoskeletal injury. In both cross-sectional and prospective studies, perceived injustice has been associated with greater chronicity and severity of pain, heightened displays of pain behaviour, the persistence of symptoms of depression and post- Sources of Injustice 5 traumatic stress, reduced functioning, and prolonged work disability (Ferrari 2015; Scott, Trost, Bernier, & Sullivan 2013; Scott, Trost, Milioto, & Sullivan 2013; Scott, Trost, Milioto, & Sullivan 2015; Sullivan, Davidson, Garfinkel, Siriapaipant, & Scott 2009; Sullivan, Thibault, et al. 2009). Perceived injustice predicts adverse pain outcomes even when controlling for other pain-related psychosocial factors, such as pain catastrophizing and fear of movement (Rodero et al. 2012; Scott & Sullivan 2012; Sullivan, Davidson, et al. 2009; Sullivan, Thibault, et al. 2009; Yakobov et al. 2014). Perceived injustice has also been shown to be more resistant to change than other pain-relatedpsychosocial variables (Sullivan et al. 2008). The negative impact of perceived injustice on recovery outcomes and its apparent resistance to change using current intervention approaches have led to questions surrounding the most optimal way to intervene clinically. Several intervention strategies have been suggested, including anger management, forgiveness-based interventions, and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy(Sullivan, Scott, & Trost 2012). However, research is still needed to test the efficacy of these interventions for mitigating the impact of perceived injustice. An important consideration in the clinical management of perceived injustice is that injustice perceptions may arise in the context of a social environment characterized by past and ongoing negligence, loss, and unfairness(Sullivan et al. 2008). For example, it is possible that the negligent actions of other drivers and employers may, in fact, have been causally related to the individual’s painful injury. It is also possible that clinicians and insurers may question the legitimacy of pain and suffering, and in turn, may fail to provide access to resources necessary to foster recovery(Fernandez & Turk 1995). In addition, significant others may fail to provide needed (or expected) support to the injured individual(Cano, Barterian, & Heller 2008). Sources of Injustice 6 To date, systematic investigation into sources of perceived injustice has not been undertaken. Greater knowledge of the range of sources that contribute to perceptions of injustice may facilitate the implementation of strategies to prevent the development of injustice perceptions following injury. Given evidence that injustice perceptions might be resistant to change once formed, efforts to prevent perceived injustice in the first place may be a more useful approach to promote recovery following injury. The purpose of this study was to investigate the sources of perceived injustice among individuals with persistent pain following musculoskeletal injury. Following completion of the IEQ, participants completed a semi-structured interview in which they were asked to discuss theirIEQ responses in greater detail, with a particular focus on their reasons for endorsing items related to loss, blame, and unfairness. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and coded to categorize the individuals and groups identified as sources of injustice andthe reasons underlying the identification of these sources. Exploratory analyses also examined sex and injury-related differences on the sources of injustice identified. Methods Participants The sample consisted of 86 individuals with persistent musculoskeletal pain (43 women, 43 men). Forty-six participants had low back pain following an occupational injury, while 40 had neck pain following a motor vehicle accident. The sample had a mean age of 39.35 years (range: 21-56 years) and a mean pain duration of 23.02 months (range: 3-249 months).The majority (95%) of the sample received a high school education or greater. The majority (58.1%) of the sample was single or divorced. At the time of the study, all participants were unemployed and receiving salary indemnity benefits from a provincial insurance program. Further details on the characteristics of the sample appear in Table 1. Sources of Injustice 7 Procedure Participants were recruited from the community and two rehabilitation centres in Montreal, Canada. Inclusion criteria included the following: Individuals of at least 18 years of age; musculoskeletal pain of at least 3 months duration in the back or neck following a motor vehicle or occupational accident; unemployed at the time of the study; and, receiving salary indemnity benefits from an injury insurer. Exclusion criteria included unemployment prior to pain onset, inability to provide written informed consent, and inability to complete the study procedures in English or French. Participantsprovided demographic information and completed self-report measures of pain intensity, disability, and symptoms of depression.Participants also completed the Injustice Experiences Questionnaire after which they completed an in-depth semi-structured interview aimed to explore in greater detail the reasons underlying their responses on this questionnaire. All participants provided written informed consent as a condition of study participation. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of McGill University. Self-report measures Pain Intensity Participants reported their current pain intensity on an 11-point numerical rating scale with the endpoints 0 (no pain) to 10 (excruciating). Self-Reported Disability The Pain Disability Index (PDI)(Gauthier, Thibault, Adams, & Sullivan 2008; Tait, Chibnall, & Krause 1990) was used to as a self-report measure of disability.Participants were asked to rate their level of disability in 7 different areas of daily living: home, social, recreational, occupational, sexual, self-care, and life support. For each domain, participants provide perceived disability ratings on an 11-point scale with the endpoints 0(no disability) Sources of Injustice 8 and 10(total disability). The PDI has been shown to be internally reliable and is significantly correlated with more objective indices of disability (Gauthier et al. 2008). Depression The PHQ-9(Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams 2001) was used to measure the severity of participants’ symptoms of depression. On this measure,participants report on the frequency with which they experience nine symptoms of depression from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score of the nine items reflects the severity of depression symptoms, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The PHQ-9 has been well validated among patients with chronic health conditions(Kroenke et al. 2001). Perceived injustice The Injustice Experiences Questionnaire (IEQ)_ENREF_9was used to measure injuryrelated perceptions of injustice (Sullivan et al. 2008). On this measure, participants are asked to rate the frequency with which they experience 12 thoughts on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time). Previous findings suggest that the IEQ yields two correlated factors reflecting components related to the ‘severity/irreparability of loss’ and ‘blame/unfairness’. Examples of items loading onto the first factor include, “Most people don’t understand how severe my condition is”, and “I just want my life back”. Examples of items loading onto the second factor include, “I am suffering because of someone else’s negligence”, and “It all seems so unfair”._ENREF_9The IEQ has been shown to have high internal reliability and to be valid for use among individuals with persistent musculoskeletal pain following injury (Scott et al., 2013b; Sullivan et al., 2008). Demographic Variables Participants responded to questions concerning their age, sex, education, marital status, and pain onset and duration. Sources of Injustice 9 Semi-structured interview A semi-structured interview schedule was created for the purpose of the present study to explore in greater depth participants’ experiences of injustice in the context of their persistent pain following injury. Open-ended interview questions were created on the basis of several IEQ items to explore the reasons underlying participants’ responses on these items in greater detail. The questions included in the interview schedule covered aspects of both the ‘severity/irreparability of loss’ and ‘blame/unfairness’ facets identified in the original development and validation of the IEQ(Sullivan et al. 2008). During the interview, participants who rated IEQ items as a 1 or higher were asked to identify the individual or group of individuals they were thinking of when they made their ratings on specific items. Participants were also asked to discuss their reasons for identifying specific individuals or groups during the interview. For example, participants who endorsed the IEQ item, ‘I feel as though I’m suffering because of someone else’s negligence’ were asked to identify the person they were thinking about when they rated this item, and in what ways this person has been negligent. Several additional questions were created to examine participants’ injustice-relevant experiences with specific individuals that have been previously described in the literature as potential targets of anger for individuals with chronic pain(Okifuji, Turk, & Curran 1999). These additional questions were only asked if these sources had not already been identified by the participant in the interview. An overview of the interview schedule is presented in Appendix 1. Participants recruited from the community (n = 11) were interviewed at McGill University by a graduate student in clinical psychology or a research assistant. Participants recruited from the rehabilitation centres were interviewed by clinicians at those centres (n = 75). These participants were paired with an interviewer who was not their treating clinician to Sources of Injustice 10 minimize the potential impact of issues surrounding the therapeutic relationship on interview responses. All interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews conducted in French were translated by bilingual research assistants following transcription. Coding of interview transcripts and data analysis A coding system for analysing the transcribed interviews was developed specifically for the purpose of this study. The first author (WS) developed a preliminary coding system after reviewing the transcripts of the first 11 participants, at which point it appeared that a sufficient number of common sources had been identified to inform development of the coding system. The coding system produced was an exhaustive list of the sources of injustice that emerged from the first 11 participant interviews which included individuals and groups identified as sources of injustice and reasons for identifying these sources. The resulting coding form was designed for raters to record the presence or absence (yes/no) of these sources in each participant interview. Two raters (AM and RG) were trained to use the coding system. The raters were given a description of each code and examples of responses from the interview transcriptsrelating to the codes.During a subsequent training period, the raters each coded the transcripts of the first 11 participants. Their codes were compared during two follow-up meetings facilitated by the first author where reasons for discrepant codes were discussed andconsensus was reached regarding the most appropriate codes. Following the training period, each rater coded approximately half of the 86interview transcripts. During this process, the raters also identified any new sources of injustice that were not captured in the initial coding system and brought this to the attention of the first author. These sources were then discussed between the raters and the first author, and added to the coding system as needed.Additionally, the two raters each coded a subsample of 9interviews(10% of the sample) to assess inter-rater reliability. A Kappa coefficient of 0.93 Sources of Injustice 11 (p <0.001), 95% CI, (0.89-0.96) was obtained for all coded variables, reflecting ‘almost perfect agreement’ according to established guidelines for interpreting Kappa (Landis & Koch 1977). For the purpose of sample description, mean scores and standard deviations were computed for total scores on the measures of pain intensity, disability, symptoms of depression, and perceived injustice. Frequencies were tabulated for each of the codes derived from the coding system. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare mean scores on pain, depression, disability, perceived injustice, and number of sources of injustice between men and women and between individuals who had pain following a motor vehicle or occupational accident. Chi squared tests were used to compare sex and injury-related differences in terms of the frequencies of identifying specific sources of injustice. Results Participants’ means scores on pain intensity (M = 5.68; SD = 1.47) and symptoms of depression (M = 13.33; SD = 5.88) indicate that, on average, the sample was experiencing moderate levels of both pain and depression (Fejer, Jordan, & Hartvigsen 2005; Kroenke et al. 2001). On average, participants’ scores on pain-related disability (M = 41.25; SD = 11.97) were comparable to previous samples of individuals with long-standing musculoskeletal pain (Scott, Trost, Bernier, et al. 2013). Participants’ mean score on the IEQ was 30.15 (SD = 9.50), which is comparable to previous studies using the IEQ in patients with persistent pain following musculoskeletal injury(Sullivan et al. 2008). The mean score is above a previously identified clinical cut-off on this measure(Scott et al., 2013b). Thus, participants in the study, on average,appeared to experience clinically significant levels of perceived injustice. Women (65.1%) were more likely than men (27.9%) to be injured in a motor vehicle accident, whereas men (72.1%) were more likely than women (34.9%) to have sustained an occupational injury, χ2 = 11.97, p = 0.001.Men and women did not significantly differ in Sources of Injustice 12 terms of their scores on pain intensity, depression, self-reported disability, or perceived injustice. Likewise, there were no significant differences between participants with pain due to a motor vehicle versus an occupational accident on these variables. Individuals and groups identified as sources of injustice Table 2 lists the individuals and groups identified by participants as sources of injustice during the interviews. The majority of participants identified their employers and/or colleagues, insurers, and healthcare providers as sources of injustice. Family, significant others, friends, and strangers or society were also commonly identified. The other driver involved in the accident was identified as a source of injustice among the majority of participants with pain following a motor vehicle accident. Several sources were identified by only a few participants:the participant him or herself, fate, the government, God, and science. On average, participants identified approximately 4.17 (SD = 1.90;range = 0-9) individuals or groups as sources of injustice. Common reasons for identifying individuals and groups as sources of injustice Table 3 summarizes the reasons discussed by participants for identifying specific individuals and groups as sources of injustice. On average, participants discussed 4.94 (SD = 3.43; range = 0-19) reasons for identifying individuals and groups as sources of injustice during the interviews. Generally speaking, there appeared to be commonalities in participants’ reasons for identifying employers and colleagues, family, significant others, friends, strangers, and society. The majority of participants who identified these sources reported that they experienced punitive responses from them as a result of expressing their pain. Lack of support was also frequently discussed as a reason for identifying these sources.Among participants who identified the other driver, the most common reason given was that the other driver caused the accident. Sources of Injustice 13 In contrast, reasons discussed by participants for identifying their insurers and healthcare providers were highly varied and somewhat idiosyncratic. The most common reasons provided for identifying insurers included the following: failure to provide access to the proper treatment, inappropriate assessment of the participant’s pain and/or disability; and, inadequate insurance coverage.A number of participants also reported that they had received negative responses from their insurers as a result of expressing their pain.The most common reasons for identifying healthcare providers were: inappropriate assessment of pain and/or disability; punitive responses to the participant’s expression of pain; and, failure of the provider to give the appropriate treatment. Participants who reported that specificindividuals or groups do not understand or take their condition seriously were also asked to identify aspects of their condition that are not understood or taken seriously. The severity of pain and its impact on function and mood were the most commonly identified sources of misunderstanding (Table 4). The chronicity and variability of pain and side effects of medication were also identified as being misunderstood by others. Sex and injury-related differences on sources of injustice identified Women (41.9%) were significantly more likely than men (14.0%) to identify the other driver as a source of injustice, χ2 = 9.77, p < 0.01. Women (74.4%) also identified healthcare providers significantly more than men (51.2%), χ2 = 4.98, p < 0.05. Lastly, women (58.1%) were significantly more likely than men (32.6%) to identify family members as a source of injustice, χ2 = 5.67, p < 0.05. In contrast, a greater proportion of men (76.7%) identified their employer/colleagues as a source of injustice, as compared to women (55.8%), χ2 = 4.21, p < 0.05. Men and women did not differ significantly in terms of the average number of sources of injustice identified. Sources of Injustice 14 For the purpose of descriptive comparison, Table 5 displays the relative rank ordering of the frequency of identifying sources of injustice according to injury type. Healthcare providers were the most frequently identified source among participants injured in motor vehicle accidents, followed by insurers, other drivers, family members and employers and/or colleagues. In contrast, employers and/or colleagues were identified most frequently, followed by insurers and healthcare providers,among participants with work-related injuries. Unsurprisingly, participants injured in a motor vehicle accident (60%) were significantly more likely to identify other drivers as a source of injustice than those with occupational injuries (0.0%), χ2 = 40.5, p <0.001. In comparison, those with work-related injuries (80.4%) were significantly more likely to identify their employers and/or colleagues as a source of injustice than those injured in a motor vehicle accident (50.0%), χ2 = 8.87, p < 0.01. Participants injured in a motor vehicle accident (75.0%) were significantly more likely to identify healthcare providers than participants with work-related injuries (52.3%), χ2 = 4.77, p < 0.05. Motor vehicle injury participants (60.0%) also identified family members with greater frequency than did those with work-related injuries (32.6%), χ2 = 6.48, p =0.01. On average, participants with a motor vehicle injury (M = 4.90; SD = 1.96) identified significantly more sources of injustice than those with a work-related injury (M = 3.54; SD = 1.62), t (84) = 3.52, p = 0.001. Discussion This was the first study to systematically explore sources of injustice among individuals with persistent pain following musculoskeletal injury.The frequent identification of employers and colleagues, insurers, healthcare providers, significant others, strangers and society, and other driversas sources of injustice is consistent with the previous identification of these groups as ‘targets of anger’ among individuals with chronic pain(Okifuji et al. 1999). Sources of Injustice 15 Participants also frequently identified family members and friends as sources of injustice, suggesting that multiple relationships within an individual’s social network may be important for pain-related adjustment. This study extends previous work byusing in-depth interviews to explore reasons underlying the identification of these sources of injustice. This study is also the first to explore sex- and injury-related differences in sources of injustice. Other drivers, employers, and colleagues were frequently identified as sources of injustice for contributing to the accident and pain onset. In contrast, healthcare providers and insurers were frequently identified for failing to provide propoer assessment or treatment. This is consistent with a previous study suggesting that patients differentially attribute blame for the origin versus ongoing nature of pain (McParland & Whyte 2008). Future research should examine whether injustice perceptions regarding pain onset versus maintenanceimpact on individuals’ recovery through different mechanisms, including different emotional responses.In the context of a no-fault legal system, individuals who perceive injustice regarding pain onset may have little formal recourse to restore justice resulting from the negligence of other drivers and employers. Consequently, feelings of helplessness and depression may develop(Jackson, Kubzansky, & Wright 2006; Peterson & Seligman 1983). In contrast,in the course of ongoing interactions between patients and their insurers and healthcare providers, anger may be more likely, particularly if it serves torestore justice(Mikula, Scherer, & Athenstaedt 1998; Miller 2001). A common reason for identifying sources of injustice wasparticipants’ experience of punitive responses from these sources as a result of expressing pain.Previous research has shown that punitive and invalidating responsesfrom others and lack of social support areassociated with greater pain, disability, and distressamong individuals with chronic pain(Boothby, Thorn, Overduin, & Ward 2004; Ghavidel-Parsa et al. 2015; Kool & Geenen 2012; Leong, Cano, & Johansen 2011). The current data suggest that negativesocial Sources of Injustice 16 responses may impact pain-related adjustment by contributing to injustice perceptions. Indeed, negative interpersonal responses toward the person in pain may violate social contracts of respect and inclusion (Miller 2001; Skitka 2009). Therefore, understanding the impact of social responses on pain from an interpersonal injustice perspective may be useful for future research. Sex and injury-related differences emerged in participants’ experience of injustice. Women were more likely than men to identify other drivers, while men more frequently identified their employer, likely due to the fact that women were more frequently injured in a motor vehicle accident and men were more frequently injured at work. Interestingly, women identified healthcare providers and family members more frequently than men. Following injury, women may interact with the healthcare system more often and may be more vulnerable to ‘psychogenic’ explanations of ongoing pain (Unruh 1996). This may increase the likelihood thatwomen experience the treatment of healthcare providers as unjust.In the family setting, women may be expected to continue to take primary responsibility for childcare and household management following injury. Insofar as such responsibilities are discrepant with women’s own expectations for their roles following injury, this may give rise to women’s experiences of lack of support, invalidation, and injustice. Participants injured in a motor vehicle accident identified significantly more sources of injustice than those injured at work. The frequent identification of other drivers by these participants, which is not a relevant source of injustice for those injured at work, is one explanation for this difference. Healthcare providers and family members were also identified more frequently by participants with motor vehicle accident injuries. It is plausible that individuals with neck pain following a motor vehicle accident face greater scepticism regarding the legitimacy of their ongoing pain and disability(Cassidy et al. 2000; Ferrari & Sources of Injustice 17 Shorter 2003; Malleson 2002). In turn, scepticism from healthcare providers and family members may contribute to feelings unfair treatment among these patients. The sources of injustice identified here provide insight into potentialstrategies to prevent the development ofinjustice perceptions following injury. Greater training of healthcare providers, insurers, employers, and family members in validating communication strategies may reduce the frequency of negative interactions between these sources and individuals with pain that contribute to injustice perceptions. Briefly, validation involves communicating that another person’s experiences are legitimate and understandableby: listening and observing; accurate reflection; articulating the unverbalized; validating feelings in terms of sufficient causes and as reasonable in the moment; and, radical genuineness(Edmond & Keefe 2015; Linehan 1997). One recent study suggests trainingemployers in validating communication techniques may reduce work absence and healthcare utilization (Linton, Boersma, Traczyk, Shaw, & Nicholas 2015). Involvement of the employer in this way may be particularly important for individuals with work-related injuries, as employers were the most frequently identified source of injustice for this group in the present study. Recovery expectations of the injured patient, healthcare providers, insurers, employers, and family members could be comprehensively assessedand communicated between parties in the early stages of rehabilitation. Such an assessment could facilitate early identification and management of discrepant expectations between stakeholders. Likewise, greater communication between relevant stakeholders on decisions related to treatment, the allocation of rehabilitation resources, and workplace re-adaptation might increase the transparency of these procedures, thus reducing the likelihood that they are perceived as unfair in the future. Sources of Injustice 18 For individuals injured in motor vehicle accidents, the best way to involve the other driver in the rehabilitation plan remains uncertain at present. One particular challenge is that the other driver may not have the same degree of investment in the injured individual’s recovery as other sources identified. Where possible, efforts to facilitate the injured individual’scommunication of the impact of injury to the other driver may serve to reduce injustice perceptions by ‘educating the offender’ (Miller 2001).Where it is not possible to involve the other driver as such, forgiveness-based interventions (Wade, Worthington Jr, & Meyer 2005)might help mitigate the impact of perceived injustice regarding the other driver. The results of this study should be considered in light of several limitations.The presence of the interviewer may have influenced participants’ identification ofcertain sources of injustice for reasons of social desirability. As the majority of interviews were conducted within rehabilitation settings, participants may have been less willing to discuss experiences of injustice regarding healthcare professionals. Efforts to mitigate this included discussion of the confidentiality of the interviews during informed consent and matching participants with interviewers that were not involved in their treatment. Another point to consider is that participants for this study had pain precipitated by an injury and were not working as a result. Therefore, future research is needed to determine the generalizability of the results to participants with pain of differing etiology and with varying levels of disability. The study was conducted in the province of Quebec which operates under a no-fault insurance system. Consequently, the sources of injustice identified here may not generalize to tort systems where injured individuals are able to take legal action against the party responsible for the injury-precipitating accident. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to systematically identify sources of injustice among individuals with persistent musculoskeletal pain following injury. The data reveal the complex interpersonal context within which injustice perceptions may develop and Sources of Injustice 19 be maintained. The data suggest that prevention and management of perceived injustice will likely require interventions targeting the social context within which injustice perceptions arise. Future research is needed to test the efficacy of interventions involving multiple stakeholders for preventing perceptions of injustice following injury. References Boothby, J. L., Thorn, B. E., Overduin, L. Y., & Ward, L. C. (2004). Catastrophizing and perceived partner responses to pain. Pain, 109(3), 500-506. Cano, A., Barterian, J. A., & Heller, J. B. (2008). Empathic and nonempathic interaction in chronic pain couples. Clinical Journal of Pain, 24(8), 678-684. Cassidy, J. D., Carroll, L. J., Cote, P., Lemstra, M., Berglund, A., & Nygren, Å. (2000). Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(16), 1179-1186. Edmond, S. N., & Keefe, F. J. (2015). Validating pain communication: Current state of the science. Pain, 156(2), 215-219. Fejer, R., Jordan, A., & Hartvigsen, J. (2005). Categorising the severity of neck pain: Establishment of cut-points for use in clinical and epidemiological research. Pain, 119(1), 176-182. Fernandez, E., & Turk, D. C. (1995). The scope and significance of anger in the experience of chronic pain. Pain, 61(2), 165-175. Ferrari, R. (2015). A prospective study of perceived injustice in whiplash victims and its relationship to recovery. Clinical Rheumatology, 34(5), 975-979. Ferrari, R., & Russell, A. S. (2001). Why blame is a factor in recovery from whiplash injury. Medical hypotheses, 56(3), 372-375. Ferrari, R., & Shorter, E. (2003). From railway spine to whiplash–the recycling of nervous irritation. Medical Science Monitor, 9(11), HY27-HY37. Gauthier, N., Thibault, P., Adams, H., & Sullivan, M. J. L. (2008). Validation of a french-canadian version of the pain disability index. Pain research & management, 13(4), 327. Sources of Injustice 20 Ghavidel-Parsa, B., Maafi, A. A., Aarabi, Y., Haghdoost, A., Khojamli, M., Montazeri, A., et al. (2015). Correlation of invalidation with symptom severity and health status in fibromyalgia. Rheumatology, 54(3), 482-486. Harris, S., Morley, S., & Barton, S. B. (2003). Role loss and emotional adjustment in chronic pain. Pain, 105(1-2), 363-370. Jackson, B., Kubzansky, L. D., & Wright, R. J. (2006). Linking perceived unfairness to physical health: The perceived unfairness model. Review of General Psychology, 10(1), 21-40. Kool, M. B., & Geenen, R. (2012). Loneliness in patients with rheumatic diseases: The significance of invalidation and lack of social support. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1-2), 229-241. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The phq‐9. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606-613. Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 159-174. Leong, L. E., Cano, A., & Johansen, A. B. (2011). Sequential and base rate analysis of emotional validation and invalidation in chronic pain couples: Patient gender matters. The Journal of Pain, 12(11), 1140-1148. Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum Press. Linehan, M. (1997). Validation and psychotherapy. In G. L. Bohart A (Ed.), Empathy reconsidered: New directions in psychotherapy. Washington: American Psychological Association. Linton, S. J., Boersma, K., Traczyk, M., Shaw, W., & Nicholas, M. (2015). Early workplace communication and problem solving to prevent back disability: Results of a randomized controlled trial among high-risk workers and their supervisors. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. doi: 10.1007/s10926-015-9596-z Lyons, R., & Sullivan, M. (1998). Curbing loss in illness and disability. In Harvey J (Ed.), Perspectives on personal and interpersonal loss (pp. 579–605). New York: Taylor & Francis. Malleson, A. (2002). Whiplash and other useful illnesses: McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP. Sources of Injustice 21 McParland, J. L., & Whyte, A. (2008). A thematic analysis of attributions to others for the origins and ongoing nature of pain in community pain sufferers. Psychology, health & medicine, 13(5), 610-620. Mikula, G. (1993). On the experience of injustice. European review of social psychology, 4(1), 223244. Mikula, G. (2003). Testing an attribution‐of‐blame model of judgments of injustice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(6), 793-811. Mikula, G., Scherer, K. R., & Athenstaedt, U. (1998). The role of injustice in the elicitation of differential emotional reactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(7), 769-783. Miller, D. T. (2001). Disrespect and the experience of injustice. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 527-553. Okifuji, A., Turk, D. C., & Curran, S. L. (1999). Anger in chronic pain: Investigations of anger targets and intensity. Journal of psychosomatic research, 47(1), 1-12. Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (1983). Learned helplessness and victimization. Journal of Social Issues, 39(2), 103-116. Rodero, B., Luciano, J. V., Montero-Marín, J., Casanueva, B., Palacin, J. C., Gili, M., et al. (2012). Perceived injustice in fibromyalgia: Psychometric characteristics of the injustice experience questionnaire and relationship with pain catastrophising and pain acceptance. Journal of psychosomatic research, 73, 86-91. Scott, W., & Sullivan, M. (2012). Perceived injustice moderates the relationship between pain and depressive symptoms among individuals with persistent musculoskeletal pain. Pain research & management, 17, 335-340. Scott, W., Trost, Z., Bernier, E., & Sullivan, M. J. (2013). Anger differentially mediates the relationship between perceived injustice and chronic pain outcomes. Pain, 154, 1691-1698. Sources of Injustice 22 Scott, W., Trost, Z., Milioto, M., & Sullivan, M. (2013). Further validation of a measure of injuryrelated injustice perceptions to identify risk for occupational disability: A prospective study of individuals with whiplash injury. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 23, 557-565. Scott, W., Trost, Z., Milioto, M., & Sullivan, M. J. (2015). Barriers to change in depressive symptoms following multidisciplinary rehabilitation for whiplash: The role of perceived injustice. Clinical Journal of Pain, 31, 145-151. Skitka, L. J. (2009). Exploring the “lost and found” of justice theory and research. Social Justice Research, 22(1), 98-116. Sullivan, M. J. L., Adams, H., Horan, S., Maher, D., Boland, D., & Gross, R. (2008). The role of perceived injustice in the experience of chronic pain and disability: Scale development and validation. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 18(3), 249-261. Sullivan, M. J. L., Davidson, N., Garfinkel, B., Siriapaipant, N., & Scott, W. (2009). Perceived injustice is associated with heightened pain behaviour and disability in individuals with whiplash injuries. Psychological Injury and Law, 2, 238-247. Sullivan, M. J. L., Scott, W., & Trost, Z. (2012). Perceived injustice: A risk factor for problematic pain outcomes. Clinical Journal of Pain, 28(6), 484-488. Sullivan, M. J. L., Thibault, P., Simmonds, M. J., Milioto, M., Cantin, A. P., & Velly, A. M. (2009). Pain, perceived injustice and the persistence of post-traumatic stress symptoms during the course of rehabilitation for whiplash injuries. Pain, 145(3), 325-331. Tait, R. C., Chibnall, J. T., & Krause, S. (1990). The pain disability index: Psychometric properties. Pain, 40(2), 171-182. Unruh, A. M. (1996). Gender variations in clinical pain experience. Pain, 65(2), 123-167. Wade, N. G., Worthington Jr, E. L., & Meyer, J. E. (2005). But do they work? A meta-analysis of group interventions to promote forgiveness. Handbook of forgiveness, 423-439. Sources of Injustice 23 Yakobov, E., Scott, W., Stanish, W., Dunbar, M., Richardson, G., & Sullivan, M. (2014). The role of perceived injustice in the prediction of pain and function after total knee arthroplasty. Pain, 155(10), 2040-2046. Table 1. Sample characteristics Age (years) Variable M (SD)or N (%) 39.35 (8.82) Sex: Male Female 43 (50.0%) 43 (50.0%) Injury Type Whiplash injury Occupational injury 40 (46.5%) 46 (53.5%) Pain Location* Back Neck Upper limbs Lower limbs 78 (90.7%) 54 (62.8%) 41 (46.7%) 39 (45.3%) Time since injury (months) 23.02 (39.95) Marital Status Single In a relationship/married Divorced Widowed 41 (47.7%) 35 (40.7%) 9 (10.5%) 1 (1.2%) Education <High School High school College Undergraduate and above Missing 3 (3.5%) 43 (50.0%) 22 (25.6%) 17 (19.8%) 1 (1.2%) Pain Intensity Disability Depression Perceived Injustice Number of Sources of Injustice 5.68 (1.47) 41.25 (11.97) 13.33 (5.88) 30.15 (9.50) 4.17 (1.90) Sources of Injustice *Responses are not mutually exclusive. Table 2. Individuals and groups identified as sources of injustice Source n (%) Employer and/or colleagues 60 (70.0%) Insurer (incl. insurer physician) 57 (66.3%) Any Healthcare Provider 54 (62.8%) Physician 44 (51.2%) 14 (20.9%) Physiotherapist 7 (8.1%) Occupational Therapist 4 (4.6%) Medical System 3 (3.5%) Emergency personnel Acupuncturist 1 (1.2%) Family 39 (45.3%) Significant Other 37 (43.0%) Friends 29 (33.7%) Other Driver 24 (27.9%) Society/strangers 18 (20.9%) Self 6 (7.0%) Fate 4 (4.7%) Government 3 (3.5%) God 2 (2.3%) Science 1 (1.2%) *Note. Responses are not mutually exclusive 24 Sources of Injustice 25 Table 3. Reasons for identifying individuals and groups as sources of injustice Source Employer and/or colleagues (n = 60) Insurer, including insurance physician (n = 57) Health Care Providers (n = 54) Family (n = 39) Significant Other (n = 37) Friends (n = 29) Other driver (n = 24) Society/strangers (n = 18) Self (n = 6) Fate (n = 4) Reason for identifying source -Punitive response to pain expression/work absence -Caused accident/didn’t provide a safe workplace -Not providing support after injury -Poor communication after injury -Appropriate treatment not given -Inappropriate assessment of pain/disability -Did not provide enough financial coverage -Treated participant like a number -Punitive response to pain expression -Disorganized -Participant has to pay for treatment up front -Long wait for treatment/compensation -Does not compensate for non-Western treatment -Insurer blamed patient for accident/disability -Harassed patient -Insurer had a conflict of interest -Inappropriate assessment of pain/disability -Punitive response to pain expression -Appropriate treatment not given -Inappropriate treatment given -Did not cure pain -Long wait times -Treated participant like a number -Treatment not specialized/adapted to needs of participant -Did not give participant adequate information -Did not treat pain-related psychological problems -Blamed pain on psychological aspects of participant -Punitive response to pain expression -Does not provide needed support -Punitive response to pain expression -Does not provide needed support -Punitive response to pain expression -Does not provide needed support -Caused accident -Did not apologize for accident -Left scene after accident -Punitive response to pain expression -Caused accident -Caused accident -Equilibrium of life n (%) 43 (50.0%) 21 (24.4%) 2 (2.3%) 1 (1.2%) 17 (19.8%) 16 (18.6%) 16 (18.6%) 13 (15.1%) 13 (15.1%) 11 (12.8%) 8 (9.3%) 6 (7.0%) 4 (4.6%) 4 (4.6%) 1 (1.2%) 1 (1.2%) 25 (29.1%) 20 (23.2%) 19 (22.1%) 9 (10.5%) 6 (7.0%) 6 (7.0%) 5 (5.8%) 4 (4.6%) 2 (2.3%) 2 (2.3%) 1 (1.2%) 34 (39.5%) 12 (13.9%) 31 (36.0%) 15 (17.4%) 26 (30.2%) 9 (10.5%) 24 (27.9%) 6 (7.0%) 4 (4.6%) 15 (17.4%) 3 (3.5%) 3 (3.5%) 2 (2.3%) Sources of Injustice Government (n = 3) Science (n = 1) -Things happen for a reason -Did not prevent accident -Has not impacted ordinary people *Note. Responses are not mutually exclusive Table 4. Sources of Misunderstanding n (%) Source Severity of pain 29 (33.7%) Impact of pain on function 26 (30.2%) Impact of pain on mood 13 (15.1%) Chronicity of pain 10 (11.6%) Variability of pain 10 (11.6%) Side effects of medication 3 (3.5%) *Note. Responses are not mutually exclusive. 1 (1.2%) 2 (2.3%) 1 (1.2%) 26 Sources of Injustice 27 Table 5.Ranking of sources of injustice identified according to injury type. Motor Vehicle Accident n (%) Occupational Injury n (%) 1. Any Healthcare Provider 30 (75.0%) 1. Employer and/or colleagues 39 (84.8%) 2. Insurer 29 (72.5%) 2. Insurer 28 (60.9%) 3. Other driver 24 (60.0%) 3. Any Healthcare Provider 24 (52.2%) 3. Family 24 (60.0%) 4. Significant others 19 (41.3%) 5.Employer and/or colleagues 21 (52.5%) 5. Family members 15 (32.6%) 6. Significant other 18 (45.0%) 5. Friends 15 (32.6%) 7. Friends 14 (35.0%) 7. Society/Strangers 6 (13.0%) 8. Society/strangers 12 (30.0%) 8. Self 3 (6.5%) 9. Government 3 (7.5%) 9. Fate 2 (4.3%) 9. Self 3 (7.5%) 9. God 2 (4.3%) 11. Fate 2 (5.0%) 10. Other Driver 0 (0.0%) 12. Science 1 (2.5%) 10. Government 0 (0.0%) 13. God 0 (0.0%) 10. Science 0 (0.0%) *Note. Responses are not mutually exclusive Sources of Injustice 28 Appendix 1. Semi-structured interview schedule. Follow-up to IEQ item 1 Follow-up to IEQ item 8 Follow-up to IEQ item 3 Additional Questions Questions and Probes You endorsed the statement, ‘Most people don’t understand the severity of my condition’: - Who specifically does not understand the severity of your condition? - Why do you feel this individual (or group) does not understand? -Are there specific aspects about your condition that are not understood? You endorsed the statement, ‘I worry that my condition is not being taken seriously’: - Who specifically is not taking your condition seriously? - Why do you feel this individual (or group) is not taking your condition seriously? -Are there specific aspects about your condition that are not taken seriously? You endorsed the statement, ‘I am suffering because of someone else’s negligence’: -Who specifically has been negligent? -How has this individual/group been negligent or contributed to your suffering? -Who was responsible for your initial injury? -In the context of your pain condition, have you ever felt frustrated or angry in your interactions with your healthcare providers, insurer, employer, or significant other? -If yes (for all that apply), what has this person done to make you frustrated or angry? Have you ever felt they did not understand your condition or were not giving you the treatment or support you deserved? Why did you feel this way? Note: IEQ, Injustice Experiences Questionnaire Sources of Injustice 29