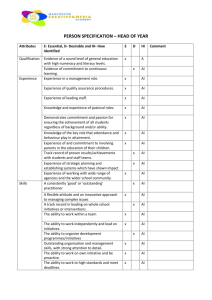

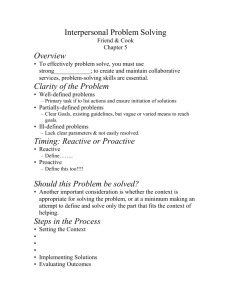

Full text - Georgetown University Law Center

advertisement