31295015065211.

advertisement

Copyright by

Jerold L. Parmer

1973

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ENTERPRISE THEORY

TO DETERMINE ITS IMPLICATIONS

IN ACCOUNTING

by

JEROLD L. PARMER, B.B.A.. M.B.A.

A DISSERTATION

IN

BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty

of Texas Tech University in

Partial Fulfillment of

the Requirements for

the Degree of

DOCTOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION

/ 7 73

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I wish to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Frsuik

J. Imke, chairman and director of this dissertation, for his

encouragement and assistance.

I gratefully acknowledge the

helpful criticism of the other members of my committee. Professors Samuel W. Chisholm, William P. Dukes, and Doyle Z.

Williams.

Their comments and suggestions resulted in many

improvements.

Finally, to my wife, Polly Ann, I give a special thanks

for helping to bear the moods of composition and study.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

ii

LIST OF TABLES

vj

I.

II.

III.

INTRODUCTION

J

Background of the problem

Objectives

Scope and methodology

Significance of the dissertation

Organization

^

1

'

i

S

COMPARISON OF THEORIES OF EQUITY

IJ

Proprietary theory

•

Legal foundation

Control, risk, income

Entity theory

.....

Position of management

Distinction between owners and

corporation . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Productive economic unit

Fund theory

Operational viewpoint . . . . .

Deemphasis of net income

.

Commander theory

Summary

IJ

Ij

li

IS

2C

RESIDUAL EQUITIES

3*;

21

22

2f

27

2$

31

3^

Nature of residual equities

l"/

Flow of receipts

hi

Position of stockholders

^2

Significance of balance sheet

k^

Expense or distribution of earnings

4*

Interest payments

i^]

Income taxes

4^

Dividends

5]

Residual equity in a cooperative

5;

Sources of capital

5]

Effect on theories of equity . . . . . . 5I

Summary

'

6(

• ••

111

IV. ENTERPRISE THEORY

V.

62

Evidences of social concept . . . . . . . . .

An activity concept

Operationalism

Examination of concept

Development of the theory

Enterprise concepts of profit

Enterprise concepts of assets . . . . .

Enterprise concepts of revenue and

expense

Enterprise concepts of equity

Summary

62

65

69

7^

7^

79

85

88

91

9^

EXAMINATION OF VALUE ADDED CONCEPT

95

Comparison of asset flows

96

Circular flow effect

96

Value added concept of income

99

Limitations of proprietary and entity

theories

100

Social accounting for the nation

101

National income accounting

101

Examples of value added income

statements

103

Comparison of accounting and economic

concepts of value added

I06

Advantages of value added concept . . . IO9

Value added taxes

Ill

Method of taxation

...Ill

Advantages

113

Disadvantages

115

Summary

117

VI.

STATEr/IENTS OF OPERATIONS

119

Comparison of funds and income statements . .120

Background of statements

120

Algebraic comparison of statements . . . 122

Direct comparison of statements . . . . 126

Analysis of funds statements

133

Funds as cash

133

Funds as net quick assets

137

Funds as net working capital

139

Comparison of funds statements

1^2

Flow statements and the enterprise theory . . 1^6

Asset flows for investors

1^9

Asset flows for long term debt holders . 153

Asset flows for short term creditors . . 155

Asset flows for regulatory agencies . . 156

Asset flows for management

159

Summary

I61

iv

VII.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

I63

Summary

163

Relationship of asset flows and

profitability

165

Relationship of enterprise theory to

economic theory

I68

Allocation of revenues among factors

of production

170

Conclusions

173

Viewpoint with respect to management . .175

Nature of assets

176

Nature of capital

177

Nature of income

177

Emphasis of concepts

178

BIBLIOGRAPHY

I83

LIST OF TABLES

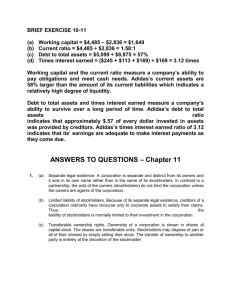

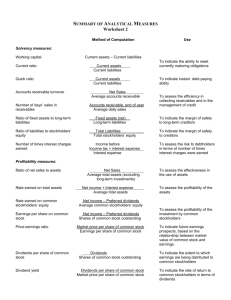

1.

Comparisons of Theories of Equity

35

2.

Concepts of Net Income

83

3.

Consolidated Business Income and Product

Accounts, 1965

107

4.

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Balance Sheets

128

5.

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Income Statements

129

6.

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Changes in Capital

130

7.

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Funds Statements,

Funds as All Assets Minus All Liabilities

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Funds Statements,

Funds as Cash

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Funds Statements,

Funds as Net Quick Assets

Hypothetical Firm, Comparative Funds Statements,

Funds as Current Assets Minus Current

Liabilities

8.

9.

10.

131

I36

I38

1^1

11.

Hypothetical Firm, Comparisons of Funds Statements 1^3

12.

Hypothetical Firm, Relationship of Net Income

to Value Added

158

Comparisons of Proprietary, Entity, and

Enterprise Theories

180

13.

VI

CHAPTER

I

INTRODUCTION

Background of the Problem

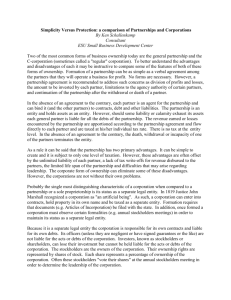

The corporation csone into existence as a vehicle for

the conduct of joint ventures.

It has grown both in size

and in importance from simple entities with a few people

acting jointly to huge complex organizations.

Originally,

liquidation of the venture with distribution of the assets

to the owners was expected.

permanent.

Now, the corporation is more

Corporate charters are granted in perpetuity.

Liquidation of the corporation is considered the exception

rather than the expected.

Corporations conduct a much larger volume of business

than any other type of business organization, including proprietorships and partnerships.

The corporation is generally

recognized as the prime business institution in the United

States.

Other forms of business entities exist but the cor

poration is the representative type of business entity in

the United States economy.

Edward Ziegler, The Vested Interests (New York: The

Macmillan Co., 1964), p. 4.

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, various

theories concerning the ownership or equities of business

organizations evolved.

etary theory.

The first of these was the propri-

The central idea of this theory is, as the

name implies, that the business is an extension of the owner.

In this scheme, assets represent things owned by the

proprietor, and liabilities are debts owed by the proprietor

This concept provided a satisfactory explanation of business

firms when businesses were small, and the owner personally

conducted or oversaw the operation of the business. Thus,

the proprietary theory is often associated with individual

proprietorships and partnerships and carries a connotation

of personal involvement by the owners.

Near the beginning of the twentieth century, the corporation began to replace the proprietorships as the dominant business organization.

The emergence of the corpora-

tion brought the recognition of the separation of ownership

and management, with the owners no longer personally conducting the operations of the business. It became difficult

to rationalize that the corporation was an agent for the

stockholder, and criticism of the proprietorship began to

arise. An alternative explanation of business ownership,

the entity theory, evolved.

The entity theory adopts the

viewpoint of the entity rather than the viewpoint of the

owners.

In this theory, accounting statements report the

accomplishments of the business.

The firm views funds

received from both stockholders and long term debt holders

as being commingled.

Both sources provide funds for the cor

duct of business.

The entity theory is generally accepted as the underlying assumption in financial reporting.

The corporation is

representative of the theory, as the corporation has a distinct separation of the business entity and the stockholder

owners.

Yet, the theory has equal application to other form

of business organizations.

For example, when the entity the

ory is accepted, the emphasis on reporting for an individual

proprietorship is on the business entity which is separate

from the individual per se.

The accounting reports show the

results of the business itself and not the status of the assets and liabilities of the owner.

While the entity theory recognizes a separation of the

owners and the business, the status of the corporation has

continued to change.

The concept of the corporation is now

much broader than just an institution in its own right.

Man

agement has come to consider itself responsible not just to

the stockholders but to all of the participants of the firm.

The idea that management has responsibilities to many groups

and even to society as a whole can be seen in a survey of th

literature.

Ezra Soloman states that in this newer ideology

profit-maximization is regarded as unrealistic, difficult, i

appropriate, and immoral.

In its place is a constellation o

objectives including service, survival, personal satisfactio

2

and satisfactory profits.

This economic change has placed increased responsibilities on accountants.

The accountant in the past has been

concerned with assisting owners to evaluate business operations.

John C. Greer states that the accountant now must

accept a broad social responsibility. Accounting reports

are the basis for significant decisions and policies in economic, social, and political matters as well as business affairs.^

Accounting thought has continued to change, also. The

entity theory has been attacked by the proponents of the

proprietary theory on the grounds that the entity theory

constitutes fiction. This attack includes the following

points. First, all business transactions must be conducted

by some person; thus, there must be a personal relationship

involved.

Secondly, a corporation is a mere legal concept;

a corporation, per se, does not possess ambitions, goals, or

even the ability to act. George R. Husband states that the

active agents of a free enterprise society are natural persons.

Free enterprise society is conducted to accomplish

their purposes.

Ezra Soloman, The Theory of Financial Management (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1963)1 P* I6.

-'w. A. Paton and A. C. Littleton, An Introduction to

Corporate Standards, intro. by Howard C. Greer (Chicago:

American Accounting Association, 19^0), p. v.

George R. Husband, "The Entity Concept in Accounting,"

The Accounting Review (October, 1954), pp. 552-63.

There is an even broader basis for the attack on the

entity theory.

If the position of the investor has become

amalgamated with the position of the other contributors of

factors of production, then, logically, accounting reports

should not be addressed to stockholders but to all interested

parties and the public in general.

Other theories that have been advanced in the literature are the residual equity theory, the funds theory, the

commander theory, and the enterprise theory.

None of these

theories has gained significant acceptance.

The residual equity theory is a compromise between the

proprietary and entity theories.

The primary point is that

while the business is the center of accounting activity, as

in the entity theory, income of the business is considered

to accrue to the owners or stockholders as in the proprietary theory.

The primary advocate of the funds theory is William J.

Vatter.^

In this theory the accounting unit is defined in

terms of a group of assets and a set of activities or functions for which these assets are employed.

assets is called a fund.

This group of

The entire notion of equity or

ownership is abandoned, and assets are accounted for in

terms of the restrictions placed upon them.

The applica-

tion of the fund theory is most apparent in the area of

^William J. Vatter, The Fund Theory of Accounting and

Its Implications for Financial Reports (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 194?).

governmental accounting, but the concept carries over in financial accounting in other fields.

The enterprise theory is a broad social concept of a

business enterprise.

The enterprise theory emphasizes the

effects of business operations on all of its participants

and in its broadest sense upon society as a whole.

This

broad, social responsibility is consistent with increased

reporting responsibilities recognized by Greer.

This in-

crease in reporting responsibilities provides the impetus

for the examination of the enterprise theory.

The enterprise theory recognizes that assets flow into

and from the firm.

This flow of assets concept is consis-

tent with the view of asset flow in economic theory

flected in the circular flow diagram.

re-

The enterprise the-

ory emphasizes that all factors of production are important

in the productive process.

No one factor is more important

than the other factors of production.

If a business entity

operates for the benefit of all interested parties, then a

broader concept than either the proprietary or the entity

theories is implied.

If a firm is to be analyzed on the basis of social considerations, then the traditional type of income statement

is not adequate.

assets.

The enterprise theory emphasizes flow of

This flow includes the disbursements that a firm

makes to the various elements of production.

A relevant

measure of income reflects the increase in value of a firm's

product during the productive process. A statement showing

this increase is a statement of value added.

Objective

The enterprise concept of the firm is not well defined

nor have its assumptions and limitations been thoroughly examined.

The thesis of this dissertation is that the enter-

prise theory represents a more viable and more relevant explsination of the structure and behavior of a business firm

in today's environment than either the proprietary or entity theories.

The objectives are to determine if the enter-

prise theory provides a better theory upon which to build

accounting principles and to define the assumptions and limitations of the theory.

Scope and Methodology

The thesis is posed that the enterprise theory represents a more viable, relevant explanation of a business firm

in today's environment. Comparisons and contrasts of the

proprietary, entity, funds, commander, and residual equity

theories are made in order to show how they are related. A

snythesis of these theories is used to develop the enterprise theory.

The enterprise theory is then contrasted to

the proprietary and entity theories. The enterprise theory

is developed in order to derive logical conclusions to aid

in the development of sound accounting principles.

8

A survey of existing literature, including books, periodicals, and unpublished materials, provides the basic information for the study.

From this survey, facts and assump-

tions needed to develop the theory are selected.

Based on

these facts and assumptions, the enterprise concepts are developed .

The concepts serve as a basis for the development of

statements to illustrate the application of the enterprise

theory to a hypothetical firm.

The concepts and the illus-

trations are the basis for the testing of the thesis.

Significance of the Dissertation

A conclusion is made that the enterprise theory does

provide a more viable and more relevant explanation of the

structure and behavior of a business firm in today's environment than either the proprietary or entity theories.

This

conclusion has an effect on both accounting theory and financial reporting.

It is shown that business operations are conducted

through transactions which cause assets to flow into and

from the firm.

This flow of assets, as observed by the en-

terprise theory, between the firm and its participants is

consistent with the conduct of business operations as viewed

in economic theory as illustrated by the circular flow diagram.

The nature of net income is examined in the light of

the flows of assets. It is shown that the firm per se cannot have net income as all receipts of the firm must equal

the disbursements of funds over the life of a business. Thus,

net income is an ambiguous term.

In order for the term to

have meaning, asset flows from the firm and the recipients

of those assets must be defined.

This view of net income is

nearer the meaning of net income as used in economic theory.

Through the ideas of asset flows of a firm and the defining

of net income, the enterprise theory contributes to an integration of the accounting and economic disciplines.

Organization

The first chapter of the dissertation provides an orientation to the various theories pertaining to corporate

stock ownership.

This chapter also serves an an introduc-

tion of the enterprise theory. Chapter II compares the proprietary, entity, funds, and commander theories and shows

that all are related and that the differences in the various

theories are due to the differences in emphasis. The third

chapter deals with residual equities and their effect upon

the various theories. The effect of residual equities in

cooperatives is examined. A full chapter is devoted to residual equities as their effects have significant implications to all other theories. The fourth chapter presents

the development of the enterprise theory.

The concepts of

the theory are developed and the nature of assets, capital.

10

and income in the enterprise theory is examined.

The fifth

chapter shows that asset flow concepts and value added statements are common to both the enterprise theory and economic

theory.

In the sixth chapter, asset flow concepts are ex-

amined and an assumed firm is used to exemplify various asset flow concepts.

Chapter seven contains the conclusions

and recommendations.

CHAPTER II

COMPARISON OF THEORIES OF EQUITY

There are several theories regarding ownership of equities of a business.

Each of these theories interprets the

operations of the business from a particular viewpoint.

De-

bate exists as to which of these theories provides the best

basis on which to construct accounting theory.

The propri-

etary, entity, funds, and commander theories are discussed

in detail in this chapter.

Proprietary Theory

Selection of the accounting unit to be included in a set

of accounts and financial statements serves to define the

scope or boundaries of a given accounting entity.

Transac-

tions coming within these boundaries must be recorded.

In

order to develop consistent accounting principles, it is important to determine the underlying accounting theory to be

used in recording the activities of the accounting unit selected.

The proprietary theory was the forerunner of all

theories and is illustrated by small businesses in which the

owner is active in the conduct of the business affairs.

These

small businesses include proprietorships, partnerships, and

small corporations.

However, the proprietary theory can be

11

12

extended to apply to a large, diverse corporation.

In a small business organization, the owners are often

personally involved in the conduct of the business operations.

In such a case, there cannot be a separation of own-

ership and management; they are the same.

However, as a

business grows, both in size and in scope of activities, it

is impossible for the owners to be personally involved; therefore, duties and responsibilities must be delegated to others.

In the corporate form the persons that perform these

duties are the officers and directors.

Stockholders elect the members of the board of directors, who in turn select the corporate officers.

However,

the stockholders retain the final authority to terminate or

change the board of directors.

The proprietary theory views

these directors and officers as employees for the owner stockholders.

Thus, the stockholders or owners have ultimate au-

thority with management acting as an agent to conduct the

owners' business.

The proprietary view of management has been influenced

by the legal position of management.

Legally, the powers of

management are considered as powers in trust which are used

in managing the corporation for the benefit of the stockholders.

The following quotation is an example:

. . . all powers granted to a corporation or to the

management of a corporation, whether derived from statue

or charter or both, are necessarily at all times exercisable only for the ratable benefit of all shareholders

13

as their interests appear.

The view by a prominent advocate of the proprietary theory emphasizing managements' relationship to the stockholders

was expressed as:

The corporation might well be viewed as a group of individuals associated for the purpose of business enterprise, so organized that its affairs are conducted

through representatives.2

Stockholders are less active in the control of many

corporations today.

Management must exercise a wider range

of control. More typically, as long as the affairs of the

corporation run smoothly and profitably, the stockholders

are unlikely to terminate or change the management group.

Legal foundation

The law recognizes two theories, the fiction theory and

the association theory, in regard to the creation and authority of corporations.^ The fiction theory holds that the law

of the land is the source of authority for a corporation.

The association theory recognizes a union of persons as the

source of authority and the laws as a regulatory power. Parallels exist between the fiction theory of law and the entity

Adolf A. Berle, Jr. and Gardner C. Means, The Modern

Corporation and Private Property (New York: The Macmillan

Co., 1933). p. 248.

2

George Husband, "The Corporate Entity Fiction and Accounting Theory," Accounting Review (September, 1938), p. 24l.

^Arthur T. Roberts, "The Proprietary Theory and the Entity Theory of Corporate Enterprise" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State University, 1955), P« 12.

14

theory of accounting and between the association theory and

the proprietary theory.

From the association viewpoint, it

may be stated that the corporation is in the position of a

trustee who uses the corporate assets for the benefit of the

stockholders.

One writer expressed this view of the association concept of corporations:

No matter how real and distinct the corporate entity

may be in the rights and duties attached to it, it is

never an inconsistency to say that the corporation is

always an association of individuals acting as a unit

in the group name.^

The proprietary theorists emphasize that the corporation holds assets in trust for the stockholders.

If the

corporation is acting as a trustee in regard to the corporate assets, it follows that the owners would have a net

value view of assets.

The emphasis is upon the remaining

value after deducting all debts against the assets.

This

approach is consistent with the formula used by proprietary

theorists, that assets - liabilities = capital.

In this equation, assets - liabilities = capital, capital represents the residue in the assets after the liabilities have been deducted.

This view emphasizes the distinc-

tion between owners and creditors.

Under the proprietary

theory, only the owners' equity is considered capital.

4James Carter, The Nature of the Corporation as a

Legal Entity (Baltimore: John Hopkins University, 1919) i

p. 36.

15

Control, risk, and income

Ownership may be defined in terms of control, risk, and

income.^

In a small unincorporated business, little contro-

versy exists over the owners having the greatest share of all

these elements.

In a corporation with a separation of duties

and functions, the owner stockholders do not clearly possess

the greatest combination of the three essential elements.

The common stockholders have the right to vote in the

selection of the directors of the corporation, and, in turn,

the directors select the corporate officers.

Thus, the stock-

holders have a voice in management and in the control of a

corporation.

In recent years, the position of ownership has

generally changed from active to passive with the growth in

size of the industrial corporation.

However, the stockhold-

ers still have ultimate control through their legal right to

elect directors.

As indicated in an earlier paragraph, stock-

holders usually acquiesce and allow the encumbent management

to remain unless the stockholders become particularly dissatisfied.

In contrast with the weakening position of stockholders

in the control of corporate activities, an increase has occurred in the influence of long term creditors in the management of corporations.

First, there is a tendency to give

^Roberts, p. 180.

Berle and Means, pp. 66-8.

16

7

creditors representation on the board of directors. Next,

control is shifted to long term creditors in numerous provisions of indenture agreements between borrowing corporations

and long term creditors. Examples include maintenance of

specified working capital, provisions for replacement of

fixed assets, provisions relating to sinking funds, restrictions on future indebtedness, and restrictions of dividends.

The question of control appears to revolve around the difference between active day to day control and final ultimate

control through voting rights.

In regard to the element of risk, the stockholders are

the first risk bearers as all losses must be fully absorbed

by the stockholders' equity before other parties suffer losses.

However, it is not uncommon that the stockholders' in-

vestments are insufficient to absorb all losses. Further,

the concept of limited liability tends to curb the magnitude

of loss that a stockholder may incur. Thus, the stockholders may be the primary risk takers, but they are not absolute as others must absorb losses also.

From an economic point of view, both long term creditors' and stockholders' investment positions depend upon the

earning capacity of the enterprise, and both are subject to

some risk.

The following statement reflects such a view:

So long as the earnings are liberal, bondholders

and stockholders share in the harvest. Both classes

'^Arthur Stone Dewing, The Financial Policy of Corporations (New York: The Ronald Press, 1953). P- 188.

17

of securities are good investments and receive money

from the same source—the earnings of the corporation.

But when earnings are small the stockholder receives

nothing although the bondholder may be paid—often to

the serious distress of the company. When, however,

the earnings decline further the payment to the bondholder, too, is stopped. . . . Bondholders thus assume

economic risks which do not differ very much from those

of stockholders owners.°

However, the proprietary theory takes a different view

of capital, emphasizing a difference in nature. From the

proprietary view, a purchase of stock by an investor represents ownership of the corporation's assets, whereas bondholders make loans to the corporation.

This view is repre-

sented by the following statement:

The holders of capital stock own the equity in the assets which remain after the debts of the corporation

are paid. Capital stock, therefore, means proprietorship, ownership or per cent control of the business.

A share is a fractional interest in the equity of a

corporation.°

The proprietary theorists would thus state that stockholders take more risks as they are the first in line for

losses, the most unsecured.

However, it is not feasible to

say that stockholders are the only risk takers.

In regard to income, the purchase of a bond implies relative safety of principal and a satisfactory return.

In

contrast, the stockholder has no enforceable claim on the corporation until a dividend is declared or liquidation occurs.

Q

Benjamin Graham and David L. Dodd, Security Analysis

(New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1951). P- 38.

^Birl E. Shultz, The Securities Market and How It Works

(New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1942), p. 59«

10

Graham and Dodd, p. 38.

18

The distinction between bondholders and stockholders

is based more on a legal viewpoint than on an economic viewpoint.

Stockholders actually are concerned with reasonable

security of principal and assurance of income much in the

same terms as bondholders. The following statements are illustrative t

By the very investment in common shares, the stockholder acknowledges himself as a joint heir to the fortunes and misfortunes of the business. He risks his

capital on the skill with which his directors meet the

hazards of an ever changing economic scene. But he is,

so far as large publicly held corporations are concerned, an investor. His capital is entitled to a return, providing his corporation efficiently performs

economically desirable services for society. And as

an investor he wants to count on his return; and to comply with this demand from its shareholder, the corporation must conserve some of the large earnings in rich

years to fill out the dividends during the lean time of

poor earnings. Perhaps it is wrong and at variance with

the economic conception of the common shareholders'

contribution to industry to count on some degree of

regularity in the dividend disbursements. But he does.

And unless he can, he will not invest in the corporation's shares, and the corporation will suffer because

of the greater difficulty in obtaining capital.^^

Although the law still maintains the conception

of a sharp dividing line recognizing the bondholder as

a lender and the stockholder as a quasi-partner in the

enterprise, economically the positions of the two have

drawn together. Consequently, security holders may be

regarded as a hierarchy of individuals all of whom have

supplied capital to the enterprise and all of whom expect a return from it.^

Many companies have recognized the fact that a regular

dividend policy provides the corporation with a loyal group

^^Dewing, p. 798.

12

Berle and Means, p. 279.

19

of stockholders.

There are many similarities between con-

tracted interest paid on bonds and regular payments of dividends on stocks.

The elements of ownership-control, risk, and income

have been found to some degree in both long term creditors

and the stockholder owners.

The proprietary theory regard-

ing ownership is based primarily on a legal viewpoint, i.e.

a legal distinction between the creditors and the owners.

If one accepts the idea that the stockholders own the

business and dominate management, then, logically, the business organization is a method of doing business for the owners.

The stockholders are the nucleus, and all other par-

ties are instrumentalities to be used for the benefit of the

stockholders.13

-^ One implied objective of the business from

the proprietary viewpoint is the maximization of profits for

the owners.

The proprietary concept emphasizes personal relationships.

Persons own property and conduct transactions.

En-

trepreneurs are real live people conducting business operations for an expected profit.

Conduct of business opera-

tions would be viewed as a series of exchange transactions

between persons.

Entity Theory

It is impossible in a large corporation with hundreds

^^Roberts, p. l8l.

20

of stockholders for the stockholders to take an active part

in the administration of the corporation.

As a result, a

separation of management and ownership has evolved.

The ac-

tive participation of owners has lessened such that the owners now have only an indirect relationship with management.

Position of management

The proprietary view of management is that management

is completely dominated by the owners, or that management

is a representative of the owners.

a different viewpoint.

The entity theorists take

They regard the business organization

as an institution in its own right, separate and distinct

from the owners.

The following quotes are illustrative:

According to the entity theory, the business is regarded

as an operating unit which has an existence separate and

distinct from its natural owner or owners.^^

The business undertaking is generally conceived as an

entity or institution in its own right, separate and

distinct from the parties who furnish funds.^5

While the proprietary advocates consider management as

an instrument in the hands of the owners, the entity advocates regard the owners as secondary to management.

The

owners are suppliers of funds, similar to creditors.

One writer expressed the view of the entity theory with

respect to the position of management thus:

14

Walter G. Kell, "The Equities Concept and Its Application to Accounting Theory" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Illinois, 1952), p. 46.

•^W. A. Paton and A. C. Littleton, An Introduction to

Corporate Accounting Standards (American Accounting Association, 1940), p. 8.

21

Although management performs the function of managing

the corporate affairs, with authority delegated by

stockholders, some consider management as an entity in

itself rather than an employee of the stockholders.

The part owners previously played in the corporation

has been taken over by management. Therefore the divorce of ownership and control seems to indicate the

entity theory or a managerial approach to corporate

enterprise theory.^^

Management plays an influential part in the conduct of

affairs of a corporation. With the growth of corporate businesses, the authority of professionaJ. managers has increased

because of the efficiencies and abilities which these managers have developed.17' In some cases, management can help to

effect their perpetuance. Yet, it must be remembered that

the stockholders always have ultimate authority through voting control. While there has been a definite lessening of

control by stockholders over management, final control has

not lapsed.

Distinction between owners and corporation

From the entity line of reasoning, the corporation is a

separate and distinct entity with the emphasis on the corporation. There is a real distinction between the stockholders,

who are considered as the owners of the corporation, and the

18

corporation, which is regarded as the owner of the assets.

Arthur T. Roberts, "The Proprietary Theory and the Entity Theory of Corporate Enterprise," abstract of unpublished

Ph.D. dissertation. Accounting Review (July, 1956), p. 449.

17

'Roberts, Ph.D. dissertation, p. 25.

18

Dwight A. Pomeroy, Business Law (Cincinnati, Ohio:

Southwestern Publishing Co., 1931), p. 49.

22

Under the entity concept, the entity owns all of the

assets and owes all of the suppliers of funds, stockholders

as well as creditors. This interpretation is represented

by the formula, assets = liabilities + net worth, used by

the entity theorists.

Certain definitions of the term assets seem to emphasize the entity point of view. Examples are:

Things owned are given the title "assets." Such items

may be more completely defined as anything of monetary

value owned by a specific individual or firm regardless of whether it is material or immaterial. . . . It

is not sufficient that properties be in the possession

of a firm to be considered assets. They must be owned

by the firm.^^

The factors acquired for production which have not yet

reached the point in the business process where they

may be appropriately treated as "costs of sales" or

"expenses" are called "assets."^^

These definitions emphasize an entity approach. Part

of the emphasis from this approach is placed on the contribution that assets make to production. Further, the emphasis is on total assets, not net assets after debt claims,

as in the proprietary concept.

Productive economic unit

From a professional manager's point of view, the business organization is regarded as a productive economic unit

rather than as a method of doing business. The entity point

of view implies a managerial point of view.

19

^George K. Husband and 01in E. Thomas, Principles of

Accounting (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1935)» P* 17.

20

Paton and Littleton, pp. 25-6.

23

From the entity view, the stockholders' possession of

corporate stock does not represent ownership of the corporate assets, but is evidence of a bundle of rights.

The

stockholders have rights to share in profits, rights in distributions in a liquidation, rights to attend stockholders'

meetings, and rights to vote on corporate policies and the

selection of the board of directors.

All of these rights

are indicative of the ownership position.

In the entity theoiy, the liability claims of the creditors and the equity claims of the stockholders are claims

against the assets collectively.

This view of capital is

consistent with a managerial viewpoint.

Funds from credi-

tors and from stockholders are considered commingled.

The entity view of capital is similar to the view of

capital as used in economics and finance.

The economics

capital is defined in terms of a fund of value which may be

embodied in the physical tools of production.

The financial

management point of view is concerned with all resources, or

assets, and the various creditors' and owners' claims to the

resources and the associated earnings.

When viewed from an entity viewpoint, net income would

involve a change in the total assets rather than a change in

a stockholder's account.

Income is the increase in total

assets which results from the excess of proceeds recovered

over the associated outlays.

Emphasis is on the change of

liabilities and equity, not just on the change of owners'

equity.

24

The following definitions of income illustrate the entity viewpoint:

Net business income may be defined as the amount by

which the equities of the proprietors, and all others

furnishing capital and entitled to participate in income , are increased as a result of successful operations.^^

Under the entity or managerial approach, income is

thought of as representing the net monetary reward derived from all sources by the skillful conduct of the

enterprise. Under this view, it makes no difference

who furnished the resources. They may be stockholders, bondholders, or other parties.^^

From the entity viewpoint, all gains belong to the corporate enterprise.

The stockholders are paid a return on

their capital investment. The stockholders do not possess

a legally enforceable claim against the corporation. When

a stockholder invests in a firm, he receives a bundle of

rights, the rights to receive declared dividends, rights in

liquidation, and other rights. However, if the stockholder

wishes to regain his original investment, he is forced to

sell his stock to a third party.

If a corporation consists

of a method of conducting business, as indicated by the proprietary theory, the stockholder would not logically have

to wait for a dividend; he would have a valid claim through

ownership.

In the area of the distinction between cost and distribution of profits, the entity and proprietary theories come

21

W. A. Paton, Essentials

York: Macmillan Co., 1949). p.

22

G. H. Newlove and S. P.

(Boston: Heath and Co., 1951).

of Accounting (rev. ed.; New

78.

Gamer, Advanced Accounting

p. 392.

25

into sharp focus.

From a proprietary view, all payments to

an outsider, such as wages, tajces, and interest, are costs.

They represent a reduction in the net equity of the owners.

However, under the entity or managerial viewpoints, there is

no distinction between payments to outsiders and payments to

debt and equity holders.

pense.

All disbursements represent an ex-

From this view, dividends are not distributions of

income but represent costs of operations to the business,

similar to interest.

The entity theory places emphasis on the business entity as the center of the business activity.

Various elements,

management, capital, employees, and suppliers, contribute

their respective factors to the business organization.

Busi-

ness operations emphasize productivity in which the various

factors are blended into a final product.

All parties except

management are considered as external to the business.

Fund Theory

A strong criticism of both the proprietary and entity

theories is presented by William J. Vatter,

Vatter expresses

satisfaction with the proprietary theory in regard to single

proprietorships and partnerships.

However, the proprietary

theory has shortcomings in regard to corporations.

Indivi-

dual proprietorships have a limited life but corporations

have a continuous life.

The entity theory avoids this pro-

blem by focusing attention on the business rather than on

26

the owners of the business. The entity theory, in turn, is

inconsistent, primarily because of the personalization of

the entity.^^

Vatter indicates that continuity involves a great deal

more than mere corporate existence.

It includes assumptions

that (a) the existing pattern of economic organization, including legal rules and social attitudes, will remain unchanged; (b) the operations reflected in accounting statements will be continued in substantially the same terms as

in the past; that is, the line of products, the geographical

scope of market coverage, and the general patterns of sale

effort will persist; (c) the economic and technological factors which are relevant to the operations will continue to

exert their influence in a substantially unaltered fashion;

and (d) the techniques and the forms of managerial effort

will be carried over into the future.23-^

In addition to Vatter's criticism of continuity, he

states other criticisms. First, the entity theory requires

valuation at cost.24 Vatter does not believe that valuation

at cost permits full disclosure as accounting has grown be25

yond using any "single-valued" or general purpose theory. -^

William J. Vatter, The Fund Theory of Accounting and

Its Implications for Financial Reporting (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1947). p. 5*

^^Ibid.

24

"^^Ibid.

^^Ibid., p. 7.

27

Another criticism made by Vatter of the entity theory is

that its terminology does not possess an operational content.

For example, Vatter defines assets as service poten-

tials rather than property owned, equities as restrictions

on assets rather than claims or rights, and revenue and expense as basic flows rather than specific effects of individual transactions.

Operational viewpoint

The fund theory completely abandons a personalistic

point of view and emphasizes an operational viewpoint in

dealing with accounting problems. In the fund theory, the

basis of accounting is neither a proprietor nor a corporation.

The unit for which records are kept and reports are

made is defined in terms of a group of assets. This group

of assets is called a fund, with a meaning similar to the

meaning in the term sinking fund.

The proprietary theorists view equities as net worth of

owners; the entity theorists view equity as claims against

assets.

In the fund theory, equities are viewed as restric-

tions on the use of assets of the fund, which places condi26

tions under which the fund can be operated.

The view is

expressed by Vatter that claims do not arise against assets

but against persons. Assets are used to satisfy claims, but

these claims lie in the field of property rights, not in the

^^Ibid., p. 19.

28

property itself. ' Further, liabilities as shown on the

balance sheet represent future obligations to pay. The legal obligation does not arise until the due date of the instrument; thus, the items on the balance sheet represent anticipated legal liabilities, not real ones.

Liabilities

as shown on the balance sheet represent specific restrictions.

From the fund viewpoint, the term equity does not

encompass either claims or rights. Rather, it is a restriction on the operation of the fund.

It is from this viewpoint

that the equation, assets = restrictions, is derived.

From the fund viewpoint, retained earnings represent

restrictions by the fact that all assets are subject to specific restrictions or by the overall restriction of being

part of the fund. Appropriations of retained earnings are

more clearly interpreted by the fund theory than by any of

the other theories. Appropriations represent restrictions

by the management of the assets for a specific purpose, such

as plant expansion or repayment of bonded indebtedness. All

of the items on the right hand side of the balance sheet represent restrictions on the use of assets.

In regard to assets, Vatter emphasizes that assets are

not monetary or financial in character. Vatter states:

Assets are economic in nature; they are embodiments

of future want satisfaction in the form of service

^"^Ibid.

2^Ibid.

29

potentials that may be transformed, exchanged, or

stored against future events.29

This concept of assets is compatible with the process of accrual and deferral and eliminates the need for the idea that

costs attach."^

Expense, according to the fund theory, is

the draining off or the release of converted services of assets, even if they are not revenue producing.

Because of

the joint services nature of many expenditures, expenses cannot be measured by a transactions approach.

As it is impos-

sible to trace all of the effects of a particular transaction, expense must be measured in terms of flows rather than

by transactions.^31

Revenue, in the fund theory, is observed by the addition of new assets.

This addition may be in the form of cash

but does not necessarily have to be.

A distinctive feature

of revenue, from other asset increasing transactions, is that

the new assets are completely free of restrictions, other

32

than the residual equity restriction.^

Deemphasis of net income

In the fund theory, the concept of income has become impersonalized.

The theory does not require, but may use, the

concept of net income.

^^Ibid. , p. 17.

^Qlbid.

^^Ibid. , p. 24.

^^Ibid. , p. 25.

The fund theory emphasizes the idea

30

that a business operates to perform a service. Financial

reports, then, are more in the nature of statistical summaries emphasizing sources and applications of funds.

The fund theory also emphasizes the fact that the fund

is created for some purpose; that is, it is to be operational.

The holding, converting, and delivering of services are

the objectives of a fund.

Financial reports should be tailored to the needs of the

group to which the report is addressed rather than having a

single all-purpose statement. While it is impossible to enumerate all parties that may be interested in the financial

reports of a firm, Vatter identifies three specific groups:

33

management, social control agencies, and investors.-^-'

Management places the greatest demand of all parties on

the accounting system.

The accounting system must facilitate

the managerial process. This process includes wide ranges of

collection of data, of communications, of control suid internal check, and as an aid in various problems of policy and

34

strategy.^

Secondly, various governmental units depend upon accounting summaries in taxation, regulation of prices,

protection of creditors, and other public interest matters.

Trade and other associations use accounting data to inter3*5 Thirdly, present and prospective

pret developments.-^^

^^Ibid., p. 9.

^^Ibid., p. 8.

^^Ibid.

31

investors and creditors rely on accounting data as a basis

for their decisions. The accounting reports must be adapted

by each group to fill its specific needs.

Vatter emphasizes the distinction between the fund theory and conventional accounting:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

The fund, not some person connected with it, is

viewed as an entity.

Valuation, so far as fund accounting is concerned,

is a minor issue; the absence of income emphasis

is largely responsible for this, but the impersonalness of the entity notion obviously contributes

to this point of view.

Equities, or whatever the right-hand balance sheet

items are called, are viewed as restrictions upon

assets, not as legal liabilities; this is true not

only as to surplus but also with respect to appropriations and commitments.

The segregation of long-term from short-term items

is maintained in somewhat more definite ways when

fund accounting is employed. The funding of capital assets, long-term investments, and the like is

common practice in institutional practice.

Fund accounting for institutions and government

agencies embraces certain procedures in reporting

operating data, and there are some differences between financial and institutional concepts of revenue and expense. These differences, however, are

largely matters of valuation or of the degree to

which the accrual basis of accounting is followed.

One of the distinctive features of fund accounting

is the absence of emphasis upon "net income" and

related notions of "profit," "operating margins,"

and the like.36

Commander Theory

The proprietary theory emphasizes ownership of assets

by the.proprietor; the entity theory stresses that the corporation owns the assets of the business. The commander theory emphasizes control over assets rather than the ownership

^^Ibid. , pp. 42-3.

32

of property.

The unit for which records are kept is a human

being or a small group of human beings.

These persons have

power to deploy resources under their economic control but

of which they do not necessarily have legal ownership.-^^ Bte.ny

times references are made to the business, the club, or a department as a separate social, economic, or legal entity.

There is a tendency to think of these units as engaging in

activities.

However, it is persons who conduct activities

on behalf of other human beings.-^

The function of control

can only be exercised by humans and should be used as a view39

point in accounting activities.-^^

Investors have control over their own resources, but

they do not have control over assets transferred to a business in which there is a separation of ownership and management.

Investors exercise control over dividends after they

are distributed to them.

Control over the company's re-

sources is exercised by a hierarchy of commanders.

Every

manager has limited control over certain assets with a very

few commanders having general command over all of the com,

40

pany's resources.

Accounting reports are useful in that they are used by

37

-^'Louis Goldberg, An Inquiry Into the Nature of Accounting (Iowa City: American Accounting Association, 1965). p. l63«

^^Ibid.

^^Ibid.

^^Ibid., p. 165.

33

commanders in their control of resources.

Louis Goldberg

states:

. . . accounting records are kept, statements are prepared, and records are analyzed, by people on behalf

of people for the benefit of people.

The adoption of the commander theory does not change

the double entry methodology or the scope of activity.

The

theory emphasizes that reports should be addressed to people.

It may be noted that this address is similar to the idea expressed in responsibility accounting.

From the viewpoint of the commander theory, the balance

sheet becomes a statement dealing with the resources with

which a commander has been entrusted.

The commander con-

trols these resources but does not necessarily own them.

The

balance sheet is a statement of accountability, with the manager in a fiduciary role.42

The income statement is a summary and a measure of the

events during a period of time.43

^ These events have been

initiated not by an artificial entity but by real persons.

The income statement is a summary of the expenditures the

44

commander has made and the accompanying results.

The proprietary theory appears to be a special case of

^^Ibid., p. 167.

42

"^Ibid. , p. 171.

^^Ibid.

44

^^Ibid., p. 172.

34

the commauider theory, one in which both ownership and con5 The entity theory can also

trol are lodged in one person.4*^

be reconciled to the commander theory. Where a commander

has control over many assets, he may wish to limit or define

his responsibilities into separate entities. Thus, he may

consider each area a distinct entity but without conceding

an artificial personality.

Summary

The more salient features of each of the theories are

presented in Table 1. Each of the theories exajnined presents a different approach to the understanding of a business entity. Each theory provides a different interpretation, depending upon the viewpoint taken.

The proprietary theory represents the view of the owners. As such, management oversees the business in his behalf.

The owner views assets as belonging to him and views capital

as the remaining assets after all liabilities are deducted.

Income, then, is the increase in assets to which the owner

has claim.

The overview of the concept is that the business

is an extension of the individual and the corporation is a

method of conducting business.

In the entity theory, the viewpoint of the firm is assumed.

Thus, definitions reflect the entity view. Manage-

ment is not an employee of the owners but is one of the

^^Ibid., p. 173.

35

c

0 •

0 c ^ p<

•

-P

to H

0 +5.H

a3.H

• H -P

0

03 C

*H't-i

03 +^

Cd 03

•H cd C

u0)

•d

ccd

6

o

O

C a>

w o e

•H

03

td

.C

03 Q)

^ >

<D rH

Pip

& r .

P i - d - P -d

^

^ C C!

W O.H

B

0 C

pq cd,o Cd

•

1 03

1

(d

CD (d

03 . H

•

+>

CD f:

W H

•H cd

l=>

g

O

^

(^

^

EH

M

CO

-d

C

£

03

P<03

<D U

W

HJ

m

<

EH

W

M

CD CD

03 O

03'H

o o

^ B^

oe

<<

o ••-•

P«H

O

S

O

CO

M

«

<:

>:

O CD

e-p

M

CD d ' H

tuD CD J^

•H

Cd e _,

C QJ C

CdrH ^

c

w

S

Q) O

P^

•

03

c

(D ^ 03

^

o 0C

Cd

TJ •H

03 CD 03

+^ ^ :3

CD 0

^

03 xi

0 3 - H >>

<«{ 03 ;Q

1

o

o

03 CD

>;

J^

cd

•P

0)

•H

^

P

o

u

PH

'H xi

•

-P JH

-P

CD

f! J H - O

0 O H

gCH O

CD

rC

tOD-Pri*^

Cd s:^ o

f: 0

o

cd M+>

S

cd+^+^

H

o 0

cd-d •H 03

- p 0 ^ 03

• H ^ -P Cd

P< 0 03

Cd'H 0 C

U O

o >

0 c

S'H

o c

•

Cd-P

o

JH 0

•H g

o

cd 03

o -d 1

O

CD - d

C H

0 ^ o

^

o^

Cd

M

-d o

03 0 o

•p ^ -p

0

03

03

<xi

0 03 •

Ti

03

' H >iU

m Xi Q)

H

H

6

o

ox:

C-P

S

03^^^

c

03 ' H

•H

H

03 cd

03 C •

0 0 0

C - H J^

•H

03

13

pq

-P :3

cd+^

^ cd

0 C

0

o

,Q T J

H

cCd

Cd 03

-P 0

•H 03 4->

PH 03 ^

Cd Cd 0

o

p^xi

•p

•

0 +5

C P<

0

03 O

•H C

o

iH O

Cd

•p^::

•H -P

ft^

Cd

o ^

0 C

03 C

.H 'H

•

>>

-P

•H

13

O^

0

•

H

0 0 Cd

B W)-P

O C-H

o Cd P<

Cxi a

M O O

1

cj

^

O

.

H

Cd

03 C - P

•H ' H ' H

0

p<

0 Cd

e w) o

o

o

0 '<H - d

Cd

cd '03

c 4:: ^

H

0

0

03

Cd

•H C

0 Pi

03 ' H . H

•H-P^

03 Cd 03

Cd ^ ^

•

-P

c

0

g

0

tuo

^

Cd

Cd 0

ft P C c

e 0 ^ cd

W 03 0

03 C

.iH . H

0

C d

0

•r-i^

•

+3 0 03

cd

03

W^ <i>

0 0 c

Pi^«H

^ -P 03

0 <3) 0

0 e,c»

0

c0

0

W)

m^

C

ro

P i 03 :3 0

•

0 •H 0 • H 03

- P - P c 03

P C

0 o o •H C P<:3

S C O 03 0 Cd«H

-P

6

fto+J

U Cd

0

1

•P

•P

>

o -d

•P C •

C-H-P

<D

.C

S

EH

03

o •

• H 03 • H 03

PH

1

03

03-P

•H . H

O

&3

o

P<

+J

W

T-i

0)

03 3

a c

1

«H

Pi'd'd 0

e 0 C

0 cd c

0

cd

H 0 •H

•HCH

cd-P

+> o

c -CJ

0 03

0 Vl

0

G C

0 ^

0 0

H

03

•P

0

03

03

<

03

•H -P

03 ft

Cd 0

Xi 0

Cd

0

•H

+^

e

0

ft

0

ftC

C

M

e 0

wo

Cd

0

6

36

elements of production in its own right.

Assets are owned

by the business, and capital encompasses funds contributed

by both debt holders and equity holders.

increase in all assets.

Net income is the

The emphasis of the entity concept

is that the business entity is separate from the owners and

as such management is separate from ownership.

The funds theory does not view the firm from either the

owner's or the entity's standpoint.

impersonal.

Rather the concept is

Assets are not defined in terms of ownership

but in terms of service potentials.

restriction on the use of assets.

cept of net income is deemphasized.

Capital represents a

In this theory, the conEmphasis is placed on

the source and the application of various funds.

The em-

phasis of the concept is that a business is operational in

nature and that funds constitute a segregation of assets

of a specific purpose.

The commander theory emphasizes that all business is

conducted for the benefit of natural persons.

Thus, a

commander is one that has assets under his control.

The

commander of a business is responsible for the assets of

the firm regardless of the ownership of those assets.

CHAPTER III

RESIDUAL EQUITIES

In the prior chapter an examination was made of the

proprietary, entity, funds, and commander theories. In

all theories of equity there is a person or group of persons that possess a residual claim to the assets of the entity. The understanding of the claims that accrue to these

residual claimants is significant to the understanding of

the various theories regarding equities. An examination

is made in this chapter of the nature of these residual

equities and the relationship of residual equity to the

various equity theories. An examination is also made of

the nature of residual equity in a cooperative enterprise.

Nature of Residual Equity

George J. Staubus developed a concept of accounting to

investors based upon residual equities.

In this context,

Staubus defined residual equity as:

. . . a residual equity is a right to receive any service that the entity is capable of providing in excess

George J. Staubus, A Theory of Accounting to Investors

(Berkeley: The University of California Press, 196I), p. 19-

37

38

of those required to satisfy the definite enforceable

rights of related parties.^

Staubus indicates that in a business firm this right

typically resides in the owners; in a corporation these owners are the common stockholders.

If, hov/ever, the normal re-

sidual equity is eliminated by loss, the next ranking equity

holders, preferred stockholders or unsecured creditors, become the residual equity holders.^

The essential element of

Staubus' concept is that the rights of all claimants of a

business are enforceable in a given order.

The order fol-

lows the legal sequence of secured liabilities, unsecured

liabilities, preferred stockholders, and common stockholders.

Staubus shows that investors need information related

to the potential future cash receipts from the investment

relationship.

These future transfers of money from the firm

to the investor depend upon (a) the firm's ability to disburse cash for this purpose, (b) the legal status of the investor's expectations, and (c) the management's willingness

4

to pay the investor.. Of these items, the legal status of

the investor's expectation is the more significant for the

purpose of comparing the residual equity theory to the other theories.

^Ibid.

^Ibid.

4

George J. Staubus, "The Residual Equity Point of View

in Accounting," Accounting Review (January, 1959). p. 7.

39

Through algebraic manipulation, Staubus reaches several

conclusions.

First, for an investor that is concerned with

his position in the case of liquidation, the equation becomes:

Present cash balance plus future cash receipts minus

future cash disbursements to higher ranking equity

holders equals cash balance that will be available to

satisfy the investor in question (and lower ranking

equity holders),5

It is significant to note that the same equation would

be used by all claimants in a liquidation, but the amount

of cash available to each would be different, depending upon his rank as a claimant.

Another equation from the viewpoint of a long term lender that is expecting periodic payment is presented:

The period's cash receipts minus the period's cash disbursements that rank higher than his claim equal the

net cash receipts available to pay him (and lower ranking claimants) a periodic return.°

This equation assumes that payments for operating purposes , such as materials and wages, must be made if the firm

is to continue in business. All of these views of the cash

equation carry the idea of a sequence or order of obligations,

which in turn present the residual equity viewpoint.

Staubus emphasizes the significance of residual equity

in this manner:

From the point of view of investors as a group, the

special significance of the residual equity is that

it is a buffer to all of them (except residual equity

^Ibid. , p. 9.

^Ibid.

40

holders) and is a claim senior to none. It is also of

great significsuice to the residual equity holders as a

measure of their claim. The residual equity is the one

item on the balance sheet in which all investors have

a strong interest; it is a common meeting ground, a focal point agreeable to all.'^

Flow of receipts

Staubus' theory of accounting to investors is couched

in terms of flows of cash to claimants of the finn.

The

theory is not one of division of profits but one of priority of -claims.

This emphasis on cash helps to explain the

rise in importance of the use of funds statements.

Even

though there is a distinction between funds, generally defined as current assets minus current liabilities, and cash,

it is closer than the relationship between profits and cash.

Continuing the idea of the priority of various claimants to the assets of a firm, the claims of common stockholders will next be examined.

The stockholder's posses-

sion of corporate stock does not represent ownership of property but is evidence of a bundle of rights.

Generally, it

is accepted that the stockholder has the right to share in

the profits when a dividend is declared, the right to share

in assets in liquidation, the right to attend stockholders'

meetings to vote on corporate policy and the selection of

the board of directors, and, in cases, the preemptive right

to share in additional stock issuances.

"^Ibid. , p. 10.

41

Dividends are regarded as the distribution of profits

to the shareholders of a corporation.

of this distribution is emphasized.

The contingent nature

First, profits and as-

sets must be available before a dividend may be declared by

the directors.

Secondly, just because a corporation has re-

tained profits, the directors will not necessarily declare

a dividend.

The stockholder does not possess a claim until

the dividends are declared.

It is to be noted that the dis-

cretion lies with the directors, not with the stockholders.

The second right enumerated above is the right to share

in assets in liquidation.

However, if one accepts the going

concern concept, then liquidation is an exception and not the

expected.

The life of a corporation is normally not limited

by legal contract.

Yet, even where corporations are termi-

nated, the assets that are distributed to the stockholders

are the residual assets.

The claims of other parties must

be satisfied first, with the remaining assets being returned

to the stockholders.

The right of the stockholder to vote does provide a

deterrent power to the stockholder.

The effectiveness of

this deterrent pov/er is often questioned, particularly in

the case of large, diverse corporations.

Related to this

question of control is the preemptive right, the right to

share in future stock issuances in order for a stockholder

to maintain his proportionate position of control and of

ownership.

The preemptive right is often eliminated in pub-

lic corporations for purposes of operating convenience.

42

Position of stockholders

From the above line of thought, David H. Li states that

stockholders are left with one right, the right to receive

dividends when and if declared £uid that even this right is

o

conditional.

Li states that a stock issue is in essence a

variable annuity contract with a perpetual life and transferrable rights, with its principal represented by the offering price and annuity payments represented by dividends.^

Li continues that from this line of reasoning business

capital supplied by stockholders does not represent equity

of the stockholders but rather equity of the corporation.

As long as there is no due date for a stockholder's claim

for refund of his capital contribution, there can be no present value in the claim.

tually no claim.

Without a due date, there is ac-

A conclusion from this line of thought

is that stock price, then, is not a reflection of book value

but a capitalization of future dividends.

Li points out, however, that for a corporation to survive in an expanding economy, the corporation must grow.

For a corporation to grow, the corporation must attract additional capital, and this growth requires the honoring of

o

David H. Li, "The Nature of Corporate Residual Equity

Under the Entity Concept," Accounting Review (April, 196O),

p. 261.

^Ibid.

^Qlbid.

^^Ibid.

existing financial responsibilities, including the payment

of dividends to stockholders. A corporation may survive in

the short run without the payment of dividends, but in the

long run the corporation must honor its responsibilities.

The corporation's self interest requires an eventual payment of dividends.12

Li concludes that retained earnings represent accumulated income of the corporation and are an additional equity

of the corporation.13

^ This view is consistent with the view

expressed by Husband in regard to the entity viewpoint:

Viewed as a legal entity income earned by the corporate

endeavor is the property of the corporation, per se.

The extent that such income is retained in the business

it in effect becomes the corporation's proprietary interest in itself. To consider it otherwise, as when

it is treated as part of the book value of the stockholder's equity, is to imply acceptance of the agency

or representative point of view.l^

Staubus point out three distinct ways in which the residual equity concept differs from the proprietary concept. -^

First is the fact that creditors can become residual equity

holders.

This occurs in an abnormal situation in which the

owner's equity has been reduced to such an extent that the

general creditors become residual equity holders. Secondly,

every accounting entity has a residual equity.

In all

^^Ibid., p. 262.

^^Ibid., p. 263.

14,George R. Husband, "The Entity Concept in Accounting,"

The Accounting Review (October, 195^). p. 55^*

^^Staubus, "The Residual Equity Point of View," p. 8.

44

businesses, government organizations, or non-profit institutions, there is always some one or some group that possesses

a claim to the residual assets. Third, preferred stockholders

are usually considered as owners; however, they do not qualify as residual equity holders. A preferred stockholder, except for those possessing participating rights, possesses a

preference to dividends but does not share in the residual

of the earnings or in the assets in liquidation. Preferred

stockholders' claim to dividends is fixed in amount. To argue that such stockholders possess a claim to retained earnings is to imply that all fixed claimants, including creditors , have a claim to retained earnings.

Significance of balance sheet

In the residual equity concept, it is natural for a particular claimant to be aware of prior claimants in predicting his potential for receiving cash from a firm. However,

it is equally desirable to observe all claims that rank below his claim for all of these lower ranking claims provide

a margin of safety or a buffer.

The retained earnings of

the firm, thus, are a buffer for all claimants and provide

a measure of assurance to everyone that possesses a claim

against the firm.

From this viewpoint, it can be stated

that all claimants hold a claim to retained earnings. Emphasis is placed on all claimants, not just the common stockholders who have an interest in retained earnings, as the

size of retained earnings has a direct impact on the quality of all claims.

^5

As all claimants of a firm possess an interest in retained earnings, the accounting for retained earnings is importsuit. If retained earnings are misstated, then two possibilities exist. First, assets may also be misstated. If,

for example, assets are overstated, then retained earnings

would be overstated, thus overstating the quality of every

claim held by a creditor or stockholder.

Secondly, if re-

tained earnings are misstated, then some claim of the firm

may be misstated.

If accrued interest is not reported on a

statement, then a claim, interest payable, would be understated and retained earnings would be overstated.

If a claim

is misstated, the dual effects are an improper ranking of

claims and a misstatement of the quality of all claims

through misstated retained earnings. It is for this reason that all claimants look to the income statement, as it

represents the periodic changes in their buffer, retained

earnings.16

Expense or Distribution of Earnings

Residual equity is defined by Staubus as the right to

receive assets in excess of those required to satisfy prior

claims.

The concept of residual equity has implications for

the various theories regarding corporate equities. Transactions involving payment of interest, dividends, and income

^^ibid.

46

taxes will be examined to determine if they represent an expense to the corporation or a distribution of earnings under

the various theories.

Robert T. Sprouse made an analysis of transactions involving payments of interest, dividends, and income taxes under four separate concepts of the corporation. '^ The four